Citizens' Climate Lobby / Citizens' Climate Education

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we’re relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Donor fit:

Climate change mitigation; political advocacy;

What is the problem?

Emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases contribute to anthropogenic climate change which, in turn, has extensive negative impacts on human health and wellbeing. The World Health Organisation estimates that, by 2030, an additional 250,000 people will die each year due to the effects of climate change.1 Our modelling indicates that current emissions will increase human mortality by approximately 1 death per 258,200t of CO2-equivalent emitted (likely a high estimate of deaths/t and subject to a great deal of uncertainty). This does not, however, include the detrimental effects on biodiversity and the natural environment which are also likely to be considerable (see our full cause report for more information).

What do they do?

Citizens’ Climate Lobby (CCL) is a grassroots advocacy organisation based in the United States which advocates for climate mitigation policies such as a carbon tax-and-dividend system (sometimes called carbon fee-and-dividend).2 Supporters of CCL organise meetings with congressional representatives and produce media to advocate for emission reduction policies.3 In particular, CCL’s volunteers and programs target areas where there is relatively poor understanding of climate change and climate policy, as well as targeting members of congress in key committees and positions of authority.4 The resources, research, communication protocols and staff used by CCL, however, are sourced from sister organisation Citizens’ Climate Education (CCE).5 Likewise, the supporters and volunteers who participate in CCL meetings and outreach (currently more than 25,000) are trained and supported by CCE.6 The annual budget of CCE ($2.295 million) is roughly 10 times greater than that of CCL ($205,000).7

Citizens’ Climate Education is a sister organisation of CCL which educates citizens about the dangers of climate change and potential policy solutions.8 This is done through regional conferences, an annual international conference, online webinars,9 tailored advocacy training,10 and various other programs. CCE also provides targeted research, analysis, and other communications resources to organisations and individuals interested in reducing the impacts of climate change. Due to the larger budget of CCE in comparison to CCL, as well as the role CCE plays in educating and training CCL volunteers, we were told that additional donations to CCE are presently needed more than donations to CCL (and are hence likely to have a greater counterfactual impact on lobbying activities).11 Update: More recently, we have been told that CCL is preparing to increase its lobbying capacity for a major push in 2017 and could use up to $1,209,000, primarily to hire additional staff, and that it is now likely to have a greater funding gap than CCE (see ‘Room for more funding’ below).11

Overall evaluation

Of the advocacy organisation working on climate change which we have looked at, Citizens’ Climate Lobby (in conjunction with Citizens’ Climate Education) appears to be one of the most promising. It is also plausible that CCL and CCE are one of the most cost-effective charities at reducing CO2eq emissions, but this is extremely uncertain (a highly cost-effective but low-risk option is Cool Earth).

We consider CCL and CCE particularly promising due to the following:

- CCL advocates for a revenue-neutral carbon tax-and-dividend policy (sometimes called carbon fee-and-dividend), which is supported by evidence as a highly cost-effective method of reducing greenhouse gas emissions;121314

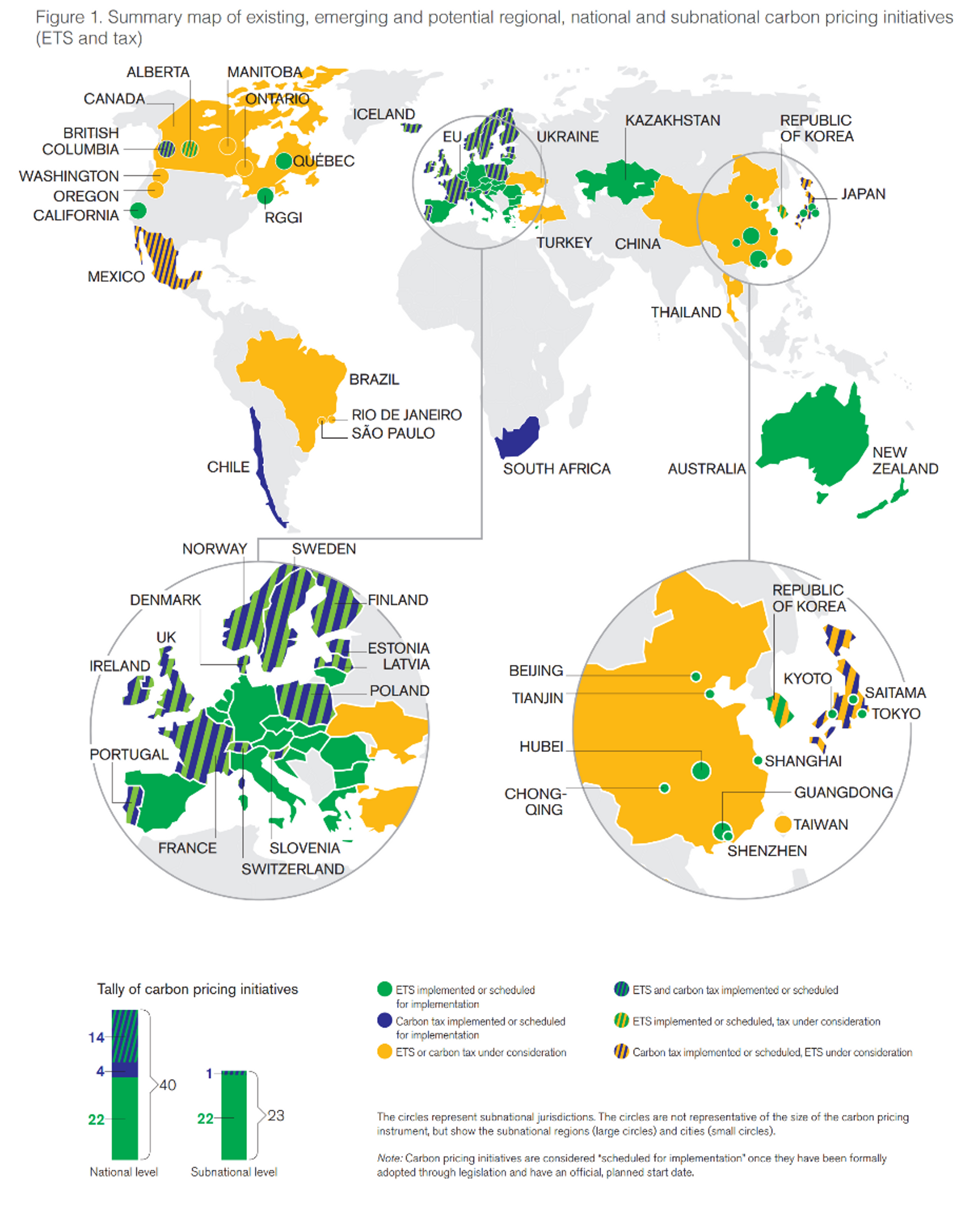

- CCL works on a federal level in the United States. Not only might legislative change in the US be a necessary step for other countries to take effective mitigation but US emissions represent a large portion of the global total, making this work particularly high-impact. The US is special as it does not have a national price on carbon planned for the future, unlike many other industrialized nations (see Figure 1 below).

- CCL has already had success in winning over Republican members of congress, which is considered a necessary condition for success in implementing carbon taxation policy. Due to increasing bipartisan support a carbon tax and dividend might be more tractable than one might think and, with the probable reshuffling in U.S. federal politics in 2017, there might be a unique window of opportunity to work on this issue.

- There now exists support for a carbon tax even withinthe fossil fuel industry;[^fn-1411]

- Even if CCL is unsuccessful at getting a carbon tax implemented, the mere prospect of a carbon tax being implemented (earlier) might lead businesses to invest in such a way that is less carbon intensive15

- CCL models its work on the anti-poverty advocacy group RESULTS, relying on grassroots supporters and advocates to approach members of congress and spread information individually.16 RESULTS has had considerable success in achieving policy changes with this model in the past.

- We think of the funding gap for grassroots initiatives for carbon tax in a similar way as that in global health, where a lot of money can be absorbed productively, because there can be more activism and a funding gap cannot easily be filled by a big donor.

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of current and planned carbon pricing schemes (now slightly outdated - Australia’s carbon tax legislation has since been repealed).17

We will not attempt to provide specific estimates of cost-effectiveness, but we consider it quite likely that CCL’s activities might result in expected impacts comparable to those of highly cost-effective direct mitigation charities such as Cool Earth.

Quality of implementation [⚫⚫⚫⚪⚪]

For lobbying and advocacy, it is much harder to rigorously evaluate a charity’s effectiveness.18 We think that most of the effectiveness of a charity is explained by the intervention a charity or lobbying organisation carries out. In other words, the most important criteria is whether the advocacy organization is lobbying for an effective cause. However the quality of their implementation and the effect of their activities to date are are clearly also important. In particular, the methods they use and their past impacts are the best indicators we have of whether they might continue to be effective. On the basis of these indicators, there is the potential that CCE may be able to reduce emissions quite effectively.

In particular, CCE and CCL have a number of useful metrics which suggest their activities may be effective. These are:

- number of letters to the editor written by volunteers and published;

- number of published opinion pieces; number of meetings with congressional offices; -

- number of personal letters written to members of congress;

- number of outreach meetings.

These metrics do not demonstrate perfectly whether the organisations may be having the desired effect or whether there might be corresponding policy progress, but they do give some indication that donations are resulting in a large amount of advocacy work being done. For instance, in 2015, the work of the 25,000 CCE-trained volunteers resulted in:

- 2,996 published letters to the editor;

- 535 published op-eds;

- 1,235 meetings with congressional offices;

- 14,934 personal letters to members of congress; and

- 1,923 outreach meetings.

As far as concrete policy achievements, CCL has not yet had any recognised successes. This may be partly due to the requirement that legislative progress must generally remain confidential, due to it taking place during meetings with legislative offices.19 Given this, there is little public evidence of CCL and CCE having the results that they are aiming for, apart from the above metrics and their rapid increase in registered supporters and volunteers, increasing at a rate of 100-200% per year and currently at over 25,000. However, one public achievement which was pointed out to us was the signing of House Resolution 424 by 13 sitting Republican Party representatives, which was acknowledged in national media.2021 This resolution “...declared the reality of climate change and of human contribution to it, and declared the need to pursue bipartisan solutions…”22 and was facilitated by volunteers from CCL and the Friends Committee on National Legislation. In addition, CCL volunteers have recently assisted in the formation of the House Climate Solutions Caucus, a bipartisan working group consisting of an equal number of Republicans and Democrats.23 Given that partisanship and the stance of Republican Party members are major obstacles to effective climate policy in the United States, this is a promising development and may indicate some progress towards CCL and CCE’s ultimate goals. In addition, there does appear to be some movement on emissions trading schemes at a state level, which is likely to benefit from CCL’s advocacy work.2425

In addition, the methods used by CCL and CCE do indicate potential for future effectiveness. From our communications, we were told that both CCE and CCL are largely modeled on the grassroots anti-poverty lobbying organisation RESULTS, which Giving What We Can has investigated briefly in the past.2627 The Citizens Climate Lobby was founded by Marshall Saunders, a former RESULTS activist. Our investigation of RESULTS and its methods found that they appeared to be highly effective. Their successes included:

- $450 million pledged by the US government in 2011 for vaccination programs delivered through the GAVI Alliance;28

- The development of the Stop TB Now Act and its incorporation into the successful Lantos-Hyde US Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act;29

- The prevention of a $300 million budget cut to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) in 2011;30

- A commitment by the US government to provide_ up to_ $5 billion to the Global Fund (although it is unclear if this $5 billion in additional funding, $5 billion per year, and/or a full $5 billion in practice rather than some smaller amount);31 and

- A $750 million commitment by the World Bank in 2010 for interest free loans for the Education for All program which works on primary education.32

It was previously estimated that RESULTS’ tuberculosis advocacy resulted in around $240 of additional public funds for every $1 spent by the charity. This appears highly cost-effective (although it is only one example of their advocacy and may not be properly representative of their work). It does give some credence to the claim that their grassroots strategy, of individuals writing letters and contacting congressional offices, is an effective one. Notably, it is this general strategy which CCL has adopted, with an additional educational component in CCE.

The main reason to expect that CCL and CCE are effective is the importance of effective climate policy being enacted in the US. The US is currently the 2nd highest emitter of greenhouse gases worldwide (contributing 15.5% of global emissions in 2014)3334 and seems likely that only political action in the United States could provoke large-scale action from a number of other nations.35 Indeed, experts have claimed that “…action in the US is necessary but not sufficient for alleviating the threat of climate change. Doing something in the United States would be likely to have a ripple effect on other countries…, and that “…Money spent on climate change might have the highest incremental effect if put towards helping Republicans form a positive agenda on the issue…”.36 CCL has already had success so far in producing exactly this effect (see above), which hints both that CCL’s work is effective and that changing Republican attitudes towards climate change is an increasingly tractable pursuit. Given that CCL and CCE are working in the one political arena where there may potentially have the greatest expected impact, this gives us further reason to believe that their efforts are well-targeted and hence potentially quite effective. Also, even if they are unsuccessful in achieving their specific legislative goals, their work in raising awareness among the general population and members of congress will likely have the ongoing benefit of making future climate action easier to achieve.

Based on their performance on the metrics mentioned above, their modest success so far, the methods with which they advocate and the parties to which they advocate, there does indeed appear to be some support for the claim that their work is both effective and high-quality. However, this is still countered by the uncertain nature of advocacy and their lack of concrete policy successes so far.

Cost-effectiveness - potentially very high, but uncertain

It is extremely difficult to estimate the cost-effectiveness of an advocacy group or lobbying organisation. It is also extremely uncertain, as past successes may not be an accurate predictor of future success (likewise, past failures may not be an accurate predictor of future failure),37 and we recognise that there is a high probability that CCL will fail to produce its intended policy changes despite using methods which are plausibly quite effective. Despite this, we will attempt to very roughly estimate the cost-effectiveness of CCL/CCE’s work.

CCL’s primary policy goal goal is to have the US government implement a revenue-neutral carbon taxation, or tax-and-dividend, policy (their full proposal available here).38 This policy involves a $15 per tonne of CO2eq emitted through fossil fuel use, rising at a consistent $10/tCO2eq each year, to be imposed at the point where these emissions first enter the economy (this may be at the the point of electricity generation or, in cases of imported goods, Carbon-tax-Equivalent Tariffs will be imposed when they are imported), to be collected by the Treasury Department.39 Similar taxes will be applied to other greenhouse gases, and corresponding Carbon-tax-Equivalent Rebates will be applied to exported goods to avoid a loss of competition.40 Once collected, these taxes will be rebated in full to individual households in monthly payments valued on a per-person basis.41

Carbon taxation, in general, is considered a highly cost-effective method of reducing emissions (although there is not universal agreement that it is the single most effective approach).4243444546 Carbon taxation policies are able to achieve emissions reductions with minimal adverse economic effects, particularly with revenue-neutrality.47484950 This has been demonstrated with carbon taxation policies implemented elsewhere, including in Australia, the European Union, British Columbia, and India.515253545556 Despite minor reductions in growth in some instances, these schemes have generally resulted in rapid and significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the areas in which they are implemented (some energy-intensive industries may simply be shifted offshore, but this can be largely avoided through elements of policy design such as the import tariffs and export rebates proposed by CCL).5758

If CCL were to succeed in getting a tax-and-dividend policy implemented, the expected reductions in emissions would be considerable. This has been confirmed in numerous studies,59 suggesting that a carbon tax of between $17 and $29 per tonne of CO2-equivalent would reduce annual emissions by between 11% and 31% by 2030.60616263 It is estimated that a $15/t tax or tax would reduce total US emissions by 14% in the short-term, although the reduction increases with time.64 Given that US emissions make up 15.5% of the global total,65 this is equivalent to a 2% reduction in global emissions, or roughly 1.1GtCO2eq less greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere per year.66 It is worth noting, however, that the eventual taxation rate advocated by CCL is considerably higher than those considered in the above studies - CCL advocates a $10/t/year increase until national emissions have reduced by 90% from 1990 levels.674

But even if CCL is unsuccessful at getting a carbon tax implemented, the mere prospect of a carbon tax being implemented (earlier than would otherwise occur) might lead businesses to invest in such a way that is less carbon intensive and also prompt investment in other emission reduction technologies.6869 Many major corporations now have internal forecasts of when carbon taxes will be implemented that guide their investment and business decisions.70

In terms of health impacts, by our modelling****, this would result in roughly 4,260 lives saved per year that this policy is in effect (not discounted with time). There is substantial uncertainty around this model and the number might higher or lower than this. With the addition of the flow-on effects of other nations following suit, this figure would likely increase considerably. Given that the policy would continue beyond just one year, the effect increases even further - per 20 years, for instance, the $15/t tax would result in 85,180 lives being saved, even if the price did not rise.

Economically, the benefits are even greater, for both this policy and government action in general. It has also been estimated that the total cost of restricting temperature rises to roughly 2°C would cost approximately 1% of Gross World Product (GWP) by 2050.71 The IPCC has estimated this cost as being higher, at 1.5-3.9% of consumption by 2050 and roughly 4.8% by 2100.72 Modelling as recent as 2016 has confirmed that this is fairly accurate, with a central estimate of 2.2% by 2050.73 This modelling also indicates that the cost will be lower the sooner the necessary policies are implemented - delaying the start of sizeable emission reductions until 2030, for instance, would result in the cost increasing by 14%.74 Furthermore, the economic costs of not doing so at all, and allowing unmitigated climate change, have been estimated to be far greater than the modest costs of mitigation, at roughly 20% of Gross World Product by 2050.7576 Even if we don’t consider the fact that carbon taxation is potentially a great deal more cost-effective than other mitigation policies, these figures suggest that ratio of benefits to costs for this policy is at least 10 to 1.

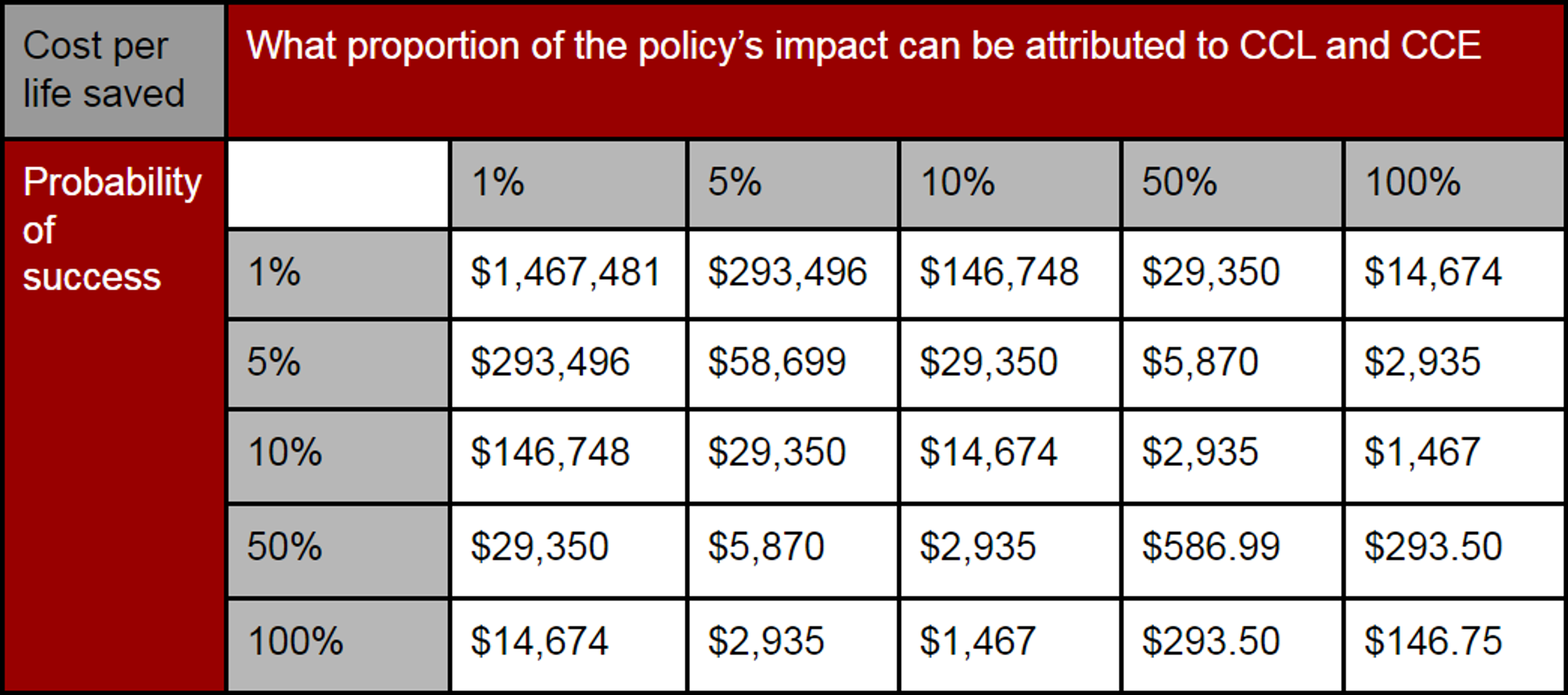

CCL operates on an annual budget of $205,000, and CCE operates on an annual budget of $2.295 million (Update: CCL is aiming to expand its activities in 2017 and aims to raise over $1.2 million for this purpose - see ‘Room for more funding’ below).77 Going purely by the effect of climate change on mortality, assuming that the policy will be in place for 20 years, assuming that CCL and CCE’s budgets remain roughly the same, and assuming that their operations are the wholly responsible if a carbon taxation policy is implemented, we can roughly suggest what their average cost-effectiveness might be if they do succeed. If they were to succeed 12 months from now,78 the cost per life saved would be a startlingly low $29.35. If it takes them 5 years - a more realistic estimate - this cost is still only $146.75 per life saved. Thus, if you suppose that CCL will succeed with 100% likelihood within 5 years, then they are roughly 20 times more cost-effective than the Against Malaria Foundation which can save a life for $3,461.79

However, these figures are purely illustrative and almost certainly an oversimplification. In reality, CCL and CCE will not be entirely responsible for any legislative changes and their likelihood of success is far from 100%. For instance, if the implementation of the policy is 50% attributable to their work and there is a 50% probability that it actually gets implemented, the cost per life saved rises to $586.99. If it is only 10% attributable to their work and there is only a 10% chance that they actually succeed, it rises to $14,674 per life saved which is no longer more cost-effective than the Against Malaria Foundation (see the table below for an illustration of cost-effectiveness under different probabilities). It could also be that the damage done per tonne of CO2 released is much higher or much lower than what our model indicates. CCL’s work and climate change mitigation in general will, of course, have impacts wider than just saving lives - such as preventing biodiversity loss, improving animal welfare, averting low-probability catastrophic scenarios, preserving natural habitats and so forth (see our full report on climate change). However, for our purposes here, the variability in cost per life saved is useful in illustrating how much CCL and CCE’s cost-effectiveness may vary.

Figure 1: Cost per life saved by CCL and CCE’s work if their $15/tCO__2__eq carbon tax is implemented in 5 years, if the policy remains in place for 20 years, if their annual budget remains constant, and if there are no flow-on effects to other countries.

Figure 1 demonstrates just how uncertain CCL and CCE’s cost-effectiveness is. We simply do not have sufficient information to suggest exactly what CCL’s probability of, or responsibility for, success actually is. They are one of the only climate change advocacy groups which have adopted the effective grassroots strategy of RESULTS and therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that, if they were successful, at least 10% of the impact could be attributable to them (although this is debatable). But even then, Figure 1 suggests that their cost-effectiveness could be as good as $146.75 per life saved or as poor as $146,748 per life saved (this is more than our rough estimate for direct mitigation charity Cool Earth, at $97,300 per life saved).

The cost per tonne of CO2-equivalent emissions averted follows a similar pattern. The above uses a rate of 258,200tCO2eq per life saved, and the above implies a cost per tonne of CO2-equivalent averted through CCL and CCE potentially as low as $0.00057 (100% probability of success and 100% attribution of responsibility) and potentially as high as $0.57 (1% probability of success and 10% attribution of responsibility).

Based on this, Citizens’ Climate Lobby and Citizens’ Climate Education may be highly cost-effective, and a great deal more so than other climate change mitigation charities. However, due to enormous uncertainty over the probability of their success and how much of that success might be attributable to their work, they may also be far less cost-effective than other alternatives. In addition to this uncertainty, we do also have some additional concerns.

Concerns:

Would volunteers advocate anyway?

There is a chance that many of the volunteers and supporters recruited by CCL and CCE would engage in advocacy even if CCL and CCE were not operating. This is plausible, at least for some portion of the 25,000 volunteers and, in particular, for advocacy activities such as letters to the editor and op-eds. Given that these activities are most likely disproportionately carried out by the most committed volunteers, this may mean that some proportion of the total impact would occur without CCL or CCE’s support. However, it is impossible to evaluate what proportion this might be.

Nonetheless, it seems unlikely that the majority of volunteers would be engaged in the same activities if it were not for the support of these organisations. It also seems unlikely that the contributions made by individuals would be as effective or of as high a quality without the education, training, and communication tools provided by CCE.80 It is also unlikely that many individuals would contact and meet with congressional offices without the coordination and practical support provided by CCE and CCL. According to CCE, a number of the most active volunteers have stated that, prior to receiving support from the organisation, they felt frustrated at their perceived inability to act on climate change.4 Although the latter is largely anecdotal evidence, it does seem more likely than not that CCL and CCE do produce a net increase in effective climate advocacy, although it may be somewhat less than the total amount of such advocacy which is carried out by their volunteers. Hence, the cost-effectiveness of CCL and CCE is likely to be somewhat reduced.

It is worth noting, however, that this is largely speculative and there is little empirical evidence to support any estimates of the likelihood of volunteers otherwise acting alone to similar ends.

Additional costs

Another significant factor in the cost-effectiveness of CCL is the inclusion of volunteer hours. When calculating the total cost of a charity or intervention, it is important to include such contributions of labour and time. After all, not only is volunteer time a tangible contribution but it also incurs an opportunity cost - if volunteers were not providing their time and labour to CCL, they could be earning more money through their regular jobs (which might be donated to advocacy activities) or otherwise participating in activities which they deem worthwhile.

Based only on budgets of CCL and CCE, it would appear that the average costs of their basic measurable achievements might be as follows:

- Roughly $100 per volunteer supported;

- $834 per letter to the editor published;

- $4,673 per op-ed published;

- $2,024 per meeting with congressional offices;

- $167 per personal letter sent to members of congress; and

- $1,300 per outreach meeting.

(Note that these costs do not overlap - the above should be interpreted as “CCL/CCE gets one letter to the editor published for every $834 donated, on average” - so every $4,500 donated results in, on average, 45 volunteers supported, 5 letters to the editor published, 1 op-ed published, 2 meetings with congressional offices, 27 personal letters to members of congress, and 3 outreach meetings)

However, when hours of volunteer work are also factored in, this all grows enormously. We were unable to obtain figures for the total amount of time volunteers devote to CCL and CCE each year but, at least for letters to the editor, we can begin to gain some idea. We know that there were 2,996 letters to the editor published in 2015 which were written by CCL volunteers. By the charity’s own estimate, between 4 and 7 letters are written for every letter published.81 If we very roughly estimate that these letters take an average of one hour each to write and send, this adds up to 23,968-41,944 hours of volunteer time spent on producing letters to the editor. With a paid staff of only 16, this indicates that CCL may produce letters to the editor quite cost-effectively just in terms of its own financial budget (at an average direct cost of $834 per letter published). However, if we value volunteer time even as low as $10 per hour, this equates to the use of an additional $239,680-$419,440 in resources per year. If we include the 535 op-eds written by volunteers, the 1,235 meetings with congressional offices, the 14,934 personal letters to members of congress, and 1,923 outreach meetings, we expect that the total cost of CCL and CCE’s operations would grow enormously (by at least one order of magnitude).

Counterfactual impact

Another factor which impacts heavily on CCL and CCE’s potential cost-effectiveness is the possibility that, even without their presence, the same or similar policies might be implemented anyway. Supposing, for instance, that their work is able to push the US government to implement a carbon price in 2020, it is entirely possible that public opinion and election outcomes would have produced the same outcome anyway or, otherwise, that such a policy would have been implemented only a few years later (however, once such a policy was implemented, they could then certainly turn their lobbying efforts towards additional climate policies and, quite probably, for increases to the carbon price chosen). This is quite plausible, as CCL’s success is dependent on having a congress which is sufficiently receptive to their appeals. For a sufficiently receptive congress, it is possible that other factors would lead them to implement effective climate policies due to general public opinion or the long-term economic benefits (see our full report on climate change).

Even if the implementation of such policies were delayed several years in the absence of CCL, and hence CCL could be seen as bringing those policies forward by several years, the actual impact of CCL’s activities would be greatly reduced. If this were a difference of five years, for instance, a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that CCL and CCE’s cost-effectiveness would be quite low: our modelling suggests that stopping global emissions entirely would only prevent 3,900 deaths per year; so stopping all emissions from the US, at 15.5% of the global total,82 would prevent roughly 610 deaths per year; this equates to 3,040 lives saved by preventing a 5-year delay; requiring an annual budget of $2.5 million, the work of CCL and CCE would only be more cost-effective than our top charities (such as the Against Malaria Foundation which can save an under-5 life for $2,838) if it were able to achieve this policy change in less than 3.5 years of work. Given that CCL was founded in 2007 and that it seems unlikely to produce change over a very short time-scale, this illustrates that actual impact of it bringing forward effective climate policy by 5 years would actually be relatively small and unlikely to be as cost-effective as the work of leading health charities. This is even with the assumption that preventing a 5-year delay would be equivalent to cutting US emissions by 100%, which isunlikely (even with the flow-on effects of other countries adopting similar policies). It also assumes a 100% likelihood of CCL being successful, which is also likely to be a considerable overestimate.

The above is largely speculative but, nonetheless, the precise counterfactual impact of CCL and CCE’s work may be far less than initially supposed when these possibilities are considered. Indeed, it seems fairly unlikely that no large-scale mitigation policy will be implemented by the US government over the next decade. Hence, even if CCL is able to effectively influence government policy, it may still not have a great deal of actual counterfactual impact, and hence may not be particularly cost-effective.

Scalability

We also have concerns about the scalability of CCL’s work and marginal impact of donations. In regards to their immediate goals of increasing registered supporters from 25,000 to 35,000 and ensuring the presence of an active chapter in every congressional district, they may already have reached a point of steeply diminishing returns. The difference of having 35,000 volunteers in comparison to having 25,000 may not be particularly large, as 25,000 volunteers are already able to do a large amount of work (see Additional Costs above), and the counterfactual impact of an additional 10,000 may be primarily to reduce the workload on the existing 25,000. Also, CCL is already represented by active chapters in 310 of 435 congressional districts, and congressional members from all 435 are already being contacted (some by CCL volunteers based in neighbouring districts). Expanding to the remaining 125 districts will hence not increase the total number of congressional members contacted but merely increase the level of contact, the quality of contact (as local advocates may be far more persuasive and hence far more effective), and decrease the workload of those volunteers which currently work in more than one district. This is not to say that finding local advocates, and hence improving the quality of contact with congressional members, will not have a considerable effect - from prior experience, CCL has observed a considerable difference in how receptive congressional members are to delegations of locals compared to delegations of advocates from other areas.4 However, this difference is largely qualitative and hence difficult to measure, and it remains the case that there will very likely be some level of diminishing marginal returns on additional volunteers as they will, primarily, improve the quality of contact with congressional members rather than further increase the number of members contacted.

Likewise, the success of CCL in terms of key metrics such as published letters to the editor and congressional meetings may not improve greatly with additional volunteers. After all, the same congressional offices may not meet with additional representatives of the same advocacy group, at least beyond some given number of meetings. After 10 meetings on the same topic, for instance, a member of congress may no longer be interested in hearing the same or similar pitch (or, at least, the marginal impact of each additional meeting will be reduced). Likewise, additional letters to the editor written by volunteers will not increase the total amount published at the same rate - for letters on the same topic, submitted to the same publications, additional letters may simply mean that editors have more to choose from rather than that they publish more letters.

Again, this is largely speculative, but it is likely that there will be sharply diminishing returns for donations to CCL and CCE beyond some point. It is also likely that their marginal cost-effectiveness is less than the average cost-effectiveness suggested by their performance to date.

Robustness of evidence [⚫⚪⚪⚪⚪]

We are not confident that CCL and CCE’s effectiveness is well-supported by evidence. This is largely due to the uncertainty involved with political advocacy.83 There are indications that they could potentially be highly cost-effective, such as:

- The high cost-effectiveness of the carbon taxation policy for which CCL advocates;848586

- The high priority of implementing such policies in the United States (see Quality of Implementation); and

- CCL’s success so far in winning over Republican members of congress, which is a necessary condition for success in implementing carbon taxation policy (this is demonstrated particularly in the signing of House Resolution 424 by 13 Republican members and the formation of the bipartisan House Climate Solutions Caucus - see ‘Quality of Implementation’ for more information);

- The past success of the advocacy group RESULTS, on which CCL models its work;87

This evidence suggests that CCL may make a large impact, in expectation, but the evidence is quite limited. CCL itself has not produced any major policy changes, to the best of our knowledge, and there is a great deal of uncertainty as to whether the above evidence means that CCL has a considerable chance of success. To claim that CCL is likely to succeed in its policy aspirations or that it is the most effective organisation to support is, therefore, largely speculative.

Given this, it is with enormous uncertainty that we claim that the work of CCL and CCE may be cost-effective and our low rating of ‘Robustness of evidence’ reflects this.

Room for more funding (✔)

Our communications with the charity have suggested that additional donations to CCL are not a high priority, as its budget is considerably smaller than that of CCE and currently requires additional volunteers more so than additional funds - specifically, CCE’s budget for 2016 is $2.295 million while CCL’s budget is only $205,000 (the majority of which is spent on international conferences and Lobby Days). These additional volunteers are sourced from, and trained by, CCE and it is hence by donating to CCE that we expect donors can have greater impact. Based on our communications with the charity, CCE does have sufficient room for more funding as it is currently seeking up to $3 million in the coming year to expand its support for volunteers, to add a Conservative Outreach specialist and dedicated Science Director, and to expand their international and regional conferences. However, CCE has also received a 2-year $500,000 grant from the MacArthur Foundation,88 is supported by several foundations,89 and has a dedicated fundraiser and grant writer.90

We have some doubts about CCE and CCL’s ability to continue to use additional funds effectively, and expect that there will be diminishing returns on donations, but it still seems likely that additional donations will continue to have a considerable positive effect. We think there is some similarity to big funding gaps in global health and development that cannot easily be filled up by high-net-worth individuals or bigger foundations, in the sense that CCL might always be able to use additional funds to raise more awareness and support for a carbon tax. However, this is not at all certain.

Update:

More recently, we have been told that CCL is preparing to increase its lobbying capacity for a major push in 2017 and, as a result, will require additional funds.4 In the next year, CCL aims to attain staffing levels in Washington D.C. sufficient to lobby for a Republican-introduced carbon tax-and-dividend bill. The primary goals of this staffing increase are to attempt to:4

- Secure Republican co-sponsors of the bill;

- Ensure strong and ongoing Democratic support; and

- Coordinating local volunteers to continue to advocate for the bill and pressure their congressional representatives to vote in favour.

In order to achieve this, CCL is seeking up to $1,209,000 in additional donations, which is intended to be used for the following:4

- Hiring four senior lobbyists, two specifically for the House and two for the Senate, “...recruited from among current congressional legislative directors and chiefs of staff [to] leverage existing networks to advance carbon fee-and-dividend legislations … among Republicans and Democrats in both the House and the Senate.” ($125,000-$150,000 each in the House and $175,000-$200,000 in the Senate);

- Hiring four associate lobbyists “...from among current congressional legislative assistants… tasked with supporting senior lobbyists, and with building networks to complement senior lobbyist congressional contacts.” ($60,000-$80,000 each);

- Larger office space to accommodate the additional staff and activity ($88,600); and

- Event expenditure of roughly $50,000 - “...Four major events for 50-100 congressional staffers, along with a modest dedicated social fund, [to] help to strengthen the congressional staff relationships necessary for eventual bill passage.

To begin with, this expansion greatly increases the combined budget of CCL and CCE and therefore, most likely, their overall funding gap. As expenses are likely to be reasonably fungible between two such closely-linked organisations (as would be donations to them), this is extremely likely to increase the marginal cost-effectiveness of donations to both organisations. In addition to this, the expansion of professional lobbying activities within Washington D.C. may plausibly be a more effective use of funds than other parts of CCE and CCL’s activities (or, at least, far more direct and therefore more obviously effective) and, thus, this may further increase the marginal cost-effectiveness of donations. This is particularly so as this expansion, a demonstrable change in the organisation’s activities, does appear to be counterfactually dependent on CCL receiving additional funding beyond what it has received in the past. The prior neglectedness of such professional lobbying within CCL, relative to grassroots advocacy, also suggests that this expansion may be quite high-impact.

It is unclear to exactly what extent these factors increase CCL’s cost-effectiveness but it is quite clear that there is a substantial increase. It also seems quite likely that CCL now requires greater levels of additional funding than CCE, although this is still somewhat uncertain. Nonetheless, we believe that it is more likely than not that donations to CCL are now somewhat more marginally cost-effective than estimated above, due to this increase in their funding gap and shift in activities.[^fn-1411]: "Exxon Touts Carbon Tax to Oil Industry - WSJ - Wall Street Journal." 2016. 22 Jul. 2016 http://www.wsj.com/articles/exxon-touts-carbon-tax-to-oil-industry-1467279004