Giving What We Can focuses on finding the charities which result in the most benefit to the greatest number of individuals. But should we give more weight to benefitting the worst off? Should we care more about equality and distributive justice?

Giving What We Can aggregates the benefits to different people additively rather than giving extra weight to worse off individuals. While our top charities tend to help some of the worst off people in the world, we do not explicitly factor considerations of fairness and equity into our cost-effectiveness calculations. There are good reasons for this:

- It’s simpler. It can be very complex to add together different benefits and also weight them differently for different people. This is why academic literature on cost-effectiveness tends to aggregate benefits additively.

- It’s less controversial. Aggregating these benefits additively relies on the ethical intuitions everyone actually has. While egalitarians care about the distribution of benefits, they also care about total benefits. Different people may have very different ideas about how much weight to place on considerations of equity. It is easier to add your own weighting than to adjust ones that we have assumed.

- It usually comes to the same answer. Those who are worst off are usually the easiest to help as there are more “low hanging fruit” so to speak.

We are certainly not suggesting that utilitarianism is the only plausible ethical theory (as has sometimes been suggested12). But we do think that aggregating benefits additively provides a good starting point, which can then be supplemented by considerations of equity and fairness if required3. We are aware that many of our members (and staff) think that prioritising helping the worst off may be of intrinsic importance, for either prioritarian or egalitarian reasons (for the purposes of this post we will refer to both as egalitarian45). Recently, we’ve been thinking more about how our recommended charities fare on these ethical dimensions.

If aggregating benefits in an additive or egalitarian manner always came to the same answer (as it often does), that would be the end of the matter. Occasionally however, we may have to make a tradeoff between helping people who are worse off or helping a larger number of people. This post is intended to give the reader some additional considerations, which may help them think about how to weigh egalitarian concerns in choosing the most effective charities.

In this post, I will argue that:

- Additive benefits are the most important consideration when choosing an effective charity. However, when the cost-effectiveness of charities is sufficiently close, it may be reasonable to factor in considerations of fairness and equity.

- All our top charities fare well on considerations of fairness and equity. This is unsurprising given that they are all charities which help children with preventable diseases in poorer countries.

- Against Malaria Foundation (AMF) fares particularly well on fairness and equity grounds as it prevents a disease with a high individual disease burden which affects the economically disadvantaged.

- It is possible that there are other comparably cost-effective charities which do better than some of our charities on fairness and equity. However, AMF sets a high bar, as it is estimated to save a life for about $3,000, and children who die under the age of five are certainly among the very worst off globally.

How to make fair choices

In 2014, the World Health Organisation published Making Fair Choices on the path to Universal Health Coverage, which attempts to provide a framework for incorporating considerations of fairness and equity into healthcare prioritisation6. The report was authored by a diverse group of 18 health economists, ethicists and practitioners in order to represent broad ethical consensus. Several members of Giving What We Can contributed to the report7.

Making Fair Choices suggests three different considerations when deciding which interventions to prioritise:

- Cost-effectiveness: How many people can be helped and how much they can be helped for a given level of resources?

- Priority for the worse off: Are the people helped particularly disadvantaged?

- Financial risk protection: How much does the intervention reduce the risk of impoverishment due to catastrophic health expenditure?8

Figure 1: Framework for integrating cost-effectiveness with other criteria when selecting services (Source: Making Fair Choices)

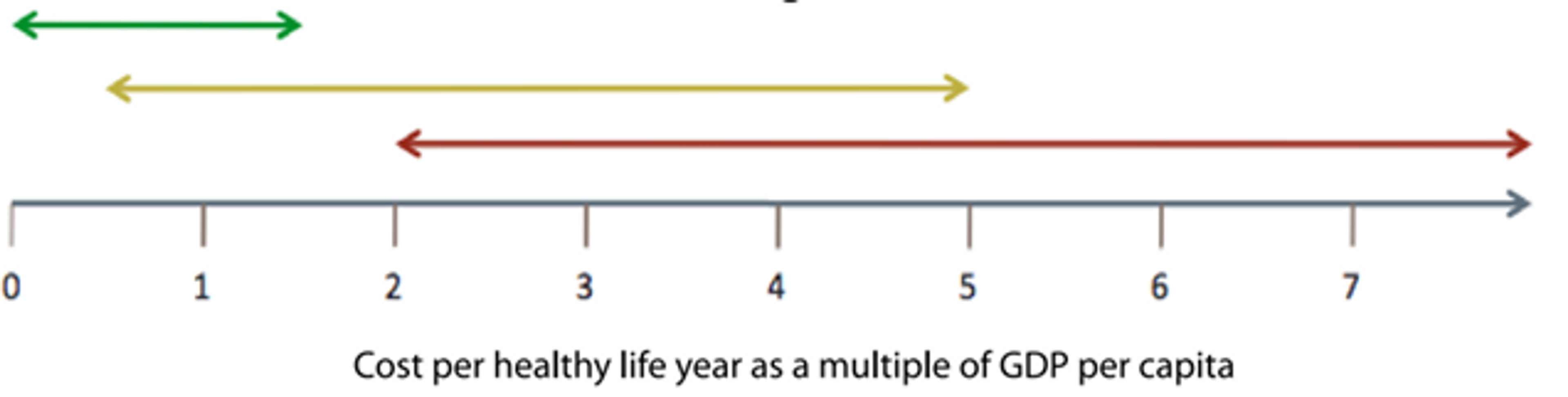

Not all these considerations should be given equal weight. The suggested decision procedure is to separate interventions into priority categories by setting overlapping thresholds for the cost-effectiveness of interventions. Where an intervention lies in the overlapping segment between different categories, considerations of priority for the worse off and financial risk protection are applied to determine which category it falls into. So while priority for the worse off is explicitly recognised as a relevant criteria for assessing which interventions to prioritise, it is only taken into account when the cost-effectiveness of two interventions is sufficiently close.

Under the example thresholds laid out in the report, all the interventions recommended by Giving What We Can fall firmly in the high priority category. That is, even if there were substantial reasons of fairness and equity to prioritise other interventions, this would only be relevant if those interventions were also within the high priority category.

However, there is still likely to be a substantial range of interventions which fall into the highly effective category and so, when the cost-effectiveness of interventions is sufficiently close, considerations of fairness and equity may come into play9.

How to evaluate fairness and equity?

One difficulty with factoring in priority for the worst off is that people can be worse off across a number of different dimensions. One solution would be to use a covering value of wellbeing which would incorporate all these considerations (such as subjective reported well being). Unfortunately, such a covering value would be very difficult to base on reliable data and highly controversial as different people value the various aspects of welfare in different ways. This mirrors the difficulties in evaluating charities on direct hedonistic grounds. In practice, consideration of who is worse off should be based on a number of different dimensions which contribute to welfare. The case studies accompanying the report (not yet released) make some suggestions10:

- Health outcomes: In the absence of the intervention, would the beneficiary bear a large individual burden of disease? The individual burden of disease can be proxied by measures such as average years of life lost (AYLL).

- Social and economic status: How badly off is the individual in terms of income, education or occupation?

So how do our top charities fare on these grounds?

Do our top recommended charities help the worst off?

| Charity | Who do they primarily help? | How badly off are they? |

| Against Malaria Foundation | Mostly children under the age of 5 who would die of malaria | Health outcomes: Very bad Those who die from malaria tend to be very young, with 65 years of life lost on average11. Social and economic status: Very bad The countries in which AMF operates are among the poorest in the world12. Even within those countries, malaria predominantly affects the poorest13. The poorest are also the groups least likely to have already purchased ITNs14. |

| Schistosomiasis Control Initiative | Children with schistosomiasis across Africa | Health outcomes: Bad The individual disease burden of schistosomiasis is far lower than that of malaria (0.5% DALY weighting. This weighting has been criticised as an underestimate as it does not account for clinical sequelae151617. Givewell use an estimate of 2-5%). However, populations who are at risk from schistosomiasis tend to live in areas with poor water and sanitation systems18, and have generally poor health prospects19. Social and economic status: Very Bad The countries in which SCI operates are among the poorest in the world20. Even within those countries, schistosomiasis predominantly affects the poorest,21 primarily in areas where fishing and irrigated agriculture represent a large segment of the economy22. Part of SCI’s programme is focused on school-based deworming and it is possible that this means the very worst off (who may not attend school) do not receive treatment23. However, the possible spillover effects of deworming24 means that those who do not receive treatment may still benefit. |

| Deworm the World Initiative | Children with soil-transmitted helminth infections across India and more recently in Ethiopia | Health outcomes: Bad The individual disease burden of soil-transmitted helminths is generally considered to be lower than schistosomiasis (Givewell use a weighting of 0.7%-1.7%). However, populations who are at risk from STH tend to have poor health prospects25. Social and economic status: Very Bad Those at risk from STH infection tend to be the poorest in a country26. STH infections are roughly twice as prevalent among socioeconomically worse off children27. India has a higher GDP per capita than most countries in which SCI operates28. However, due to high economic inequality in India, the worst off (who are most at risk from STH) are likely to be roughly equivalent in terms of social and economic status to those at risk from schistosomiasis in the countries in which SCI operates. We could not find reliable data to confirm this hypothesis. DtWI’s programme is focused on school-based deworming and it is possible that this means the very worst off (who may not attend school) do not receive treatment29. However, the possible spillover effects of deworming30 means that those who do not receive treatment may still benefit. |

| Project Healthy Children | People with micronutrient deficiencies in poorer countries. Micronutrient deficiencies have the greatest impact on children (through child development) and women (who are more likely to be anemic) | Health outcomes: Bad Micronutrient deficiency is a risk factor for a number of diseases including diarrhea, iron deficiency, iodine deficiency and lower respiratory infections31. These diseases have highly variable individual disease burdens but at least the worst, such as diarrhea are very serious32. On average, these diseases have a lower individual disease burden than malaria but higher than deworming. Social and economic status: Bad PHC operates in some of the poorest countries in the world33. Micronutrient deficiency tends to affect the economically worse off, who are unable to access a nutritious diet34. Those living in poor and rural areas sometimes remain unable to access centrally processed foods35. However, PHC take active steps to mitigate this problem by equipping smaller scale mills with fortification equipment. Women are at greater risk from iron-deficiency anemia36. |

As it turns out, all of Giving What We Can’s top charities help people who could be considered to be among the worst off in the world. This is unsurprising given that they are all charities which help people with preventable diseases in relatively poor countries. We encourage donors who value equity and fairness highly to take these considerations into account to supplement our recommendations. In practice, however, it appears that substantial tradeoffs between total benefits and considerations of fairness are rarely required. We therefore plan to continue evaluating charities on the basis of their additive benefits.

Against Malaria Foundation helps people who could plausibly be described as the very worst off in the world (children who die under the age of five). For donors who place a very high weight on justice and equality, you could do a lot worse than donating to the Against Malaria Foundation.