Out of the box and into this world: behavioural economics and international development

Studies show that people often make bad decisions. Annoyingly bad decisions, for annoyingly petty reasons. Like that time you procrastinated getting back to a friend, for no obvious reason, and it turned out you missed out on a nice dinner, an evening at the pub or some such. In fact, you probably didn’t need studies to inform you that you sometimes make bad decisions. You knew that perfectly well already.

But there is an incredible value to knowing people, in general, are not rational decision-makers. And there is an even higher value to knowing what specific biases influence their decisions and what lapses in judgement people are prone to commit. This value consists in being able to design policy interventions that help people get what they really want, often at a relatively low cost.

This opportunity is at the heart of the World Development Report (WDR) 20151, flagship publication of the World Bank. In this blog article I will outline the thinking behind the WDR and highlight a few promising opportunities for low-cost interventions.

The case for irrationality

In a recent study, Amanda Pallais2 looks at how small changes in the costs of applying to college affected application rates for students from low-income households. The small changes in costs originated from score reports of standardized tests, such as the ACT, that have to be sent by the test administrator directly to American colleges. In this case, the number of score reports that were sent free of charge increased from 3 to 4. Sending additional reports incurred a small cost of $6. What happened was that the mean number of score reports sent increased from almost exactly 3 to almost exactly 4. The effect was the same across low-income and high-income households.

Why is this strange? Well, it suggests that the students didn’t weigh the costs of sending an additional score report against the potential benefits, they simply went with the default option. Unthinking acceptance of default options seems to be pervasive in human societies, and in some cases it may have huge consequences. The students from low-income households in the example above were foregoing, on average, an additional $10,200 of lifetime earnings by not sending an additional $6 score report.

Automatic acceptance of default options is only one of many cognitive biases that people are subject to. Others include anchoring (an excessive focus on a single piece of evidence, usually the first one presented, when making a decision) and confirmation bias (the tendency to search for, interpret and focus on information in a way as to confirm your preconceived ideas).

These biases, recurring systematically and pervasively, are not in accordance with the underlying assumption of rational, utility-maximizing agents of economic models. It seems that people don’t do what they would really want to do. They fall in the traps of automatic thinking and pre-defined mental models.

This implies that a heavy usage of economic models with rational agents can lead to a situation in which we ignore incredible opportunities to improve people’s lives through interventions that recognize their cognitive biases. What’s more, this is particularly relevant for development policy, as poor countries lack many of the institutions that make good decisions default options in the West, e.g. not accepting bribes.

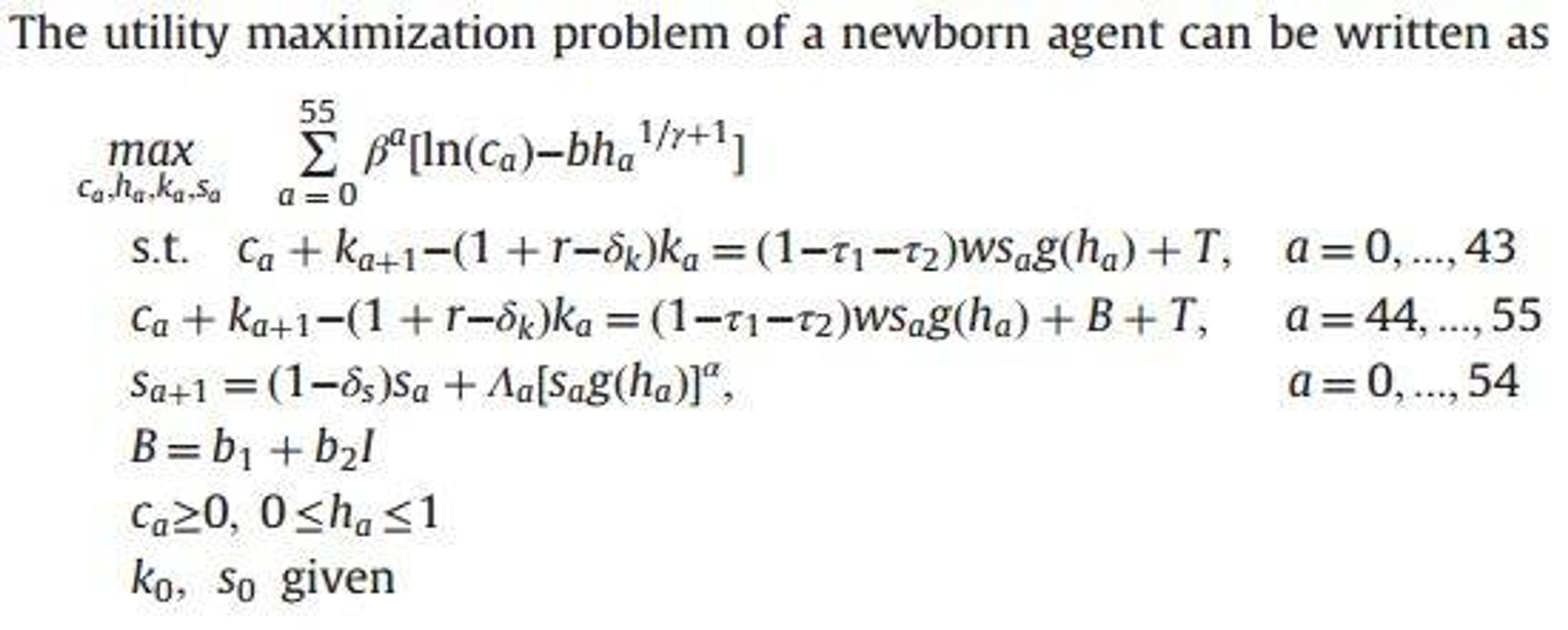

Figure 1: Good luck maximizing utility, baby.

The World Development Report 2015 draws heavily on the work of behavioural economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, and for an overview of their research I would really recommend Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.

Three principles of human decision-making

In the World Development Report 2015, the World Bank sets up a framework where human decision-making is characterized by three principles.

Thinking automatically. Lots of decisions we just make automatically, without much effort or consideration. Accepting the default option is one example of automatic thinking. Hence, minor changes to the decision-making environment can have disproportionate effects on outcomes and aggregate well-being. Such changes may relate to the timing of the decision or the design of the documents relevant for the decision.

One example comes from Mexico City, where people from low-income households were invited to pick the best $800, one-year loan from a randomized list of loan products representative of the local market. A mere 39% could identify the lowest-cost product from the brochures distributed by the banks themselves. However, 68% could do so with the help of a consumer-friendly leaflet designed by the Consumer Financial Credit Bureau. Making it easier for people to select what they want improves aggregate well-being.

Another example comes from India, where a study by Mani et. Al. (2013)3 showed how financial distress can deplete mental resources needed for important decisions. In the part of India studied, 99% of sugar cane farmers were indebted just before harvest, as opposed to 13% just after the harvest when farmers had received most of their income for the season. The financial distress had a considerable impact on farmers’ mental resources. In a series of cognitive tests, farmers performed consistently worse before harvest relative to after harvest, controlling for other factors such as sleep, work hours, nutrition etc. The mental depletion corresponded, on average, to the lack of a full night’s sleep.

With this in mind, it is perhaps less surprising that another study (Duflo, Kremer & Robinson, 2011)4 found that farmers on average make significantly higher-return investments in fertilizer straight after harvest relative to later in the season. Policy makers should therefore take real care in the timing of important decisions for the poor. Information about better seeds and crops should be distributed after harvest, not before, and farmers should be able to decide on theirs children’s schooling after harvest, not before.

Thinking socially. Humans are social animals and have innate preferences for cooperation and altruism. We are strongly affected by the social norms in our communities. This is why prevalent corruption can largely be considered a social phenomenon – if you think everyone else will accept a bribe in your position, there is little stopping you from doing so yourself. Opportunities to change social norms exist at large.

An illustrative example of this is included in Poor Economics by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo. Here we are told of school funds in Uganda, and that only 13% of the intended funds ever reached the right schools in the late 90s. After this had been publicized, there was an uproar, and the Ministry of Finance started providing the main national newspapers with statistics on how much money had been sent to local schools. The hypothesis was that the money got stuck in the pockets of local officials. 5 years after, more than 80% of the school funds reached their intended destinations.

Thinking with mental models. We use a variety of mental models when we think, passed down to us by history and culture. They are not necessarily social norms in the sense that they apply pressure on us to act in a specific way, but they are rather ways of thinking that are easily accessible. Thinking that people are rational is in some sense a mental model, particularly common amongst economists.

An example of how changes to institutions can help change mental models comes from the West Bengal in India. Here, affirmative action led to some regions having women leaders for the first time ever. Only seven years after the leaders had been elected, aspirations for teenage women were much higher. And perhaps more importantly, parents’ aspirations for their teenage daughters were higher and men’s bias in evaluating women in leadership positions was reduced (Beaman et Al, 2012)5.

Prospects?

Low-cost interventions that change behavior systematically look really promising from a development perspective. Particularly since many of the results in the World Development Report and those mentioned throughout this text have been asserted using robust statistical techniques, primarily randomized control trials. Improving decision-making environments and making good choices default options can and should improve well-being in the future. Finding such opportunities should be a clear focus for development professionals.

As a last note, we should always be aware of our own mental models and cognitive biases when thinking about development and policy interventions. And we should make sure that personal liberty is not unjustly compromised in the process of development. Helping people do what they really want, by recognizing cognitive biases, shouldn’t be considered an infringement on personal liberty. In the words of John Stuart Mill:

[It] is a proper office of public authority to guard against accidents. If either a public officer or anyone else saw a person attempting to cross a bridge which has been ascertained to be unsafe, and there were no time to warn him of his danger, they might seize him and turn him back, without any real infringement of his liberty; for liberty consists in doing what one desires, and he does not desire to fall into the river. (Mill, 1859)6