Project Healthy Children: a promising opportunity for leverage

We are excited to announce that for the first time in a while, Giving What We Can is changing its recommendations! Below we describe what is happening and answer some natural questions that flow from that.

What is happening with our recommendations?

We are splitting our recommendations into two different categories, and adding a new one to the list - Project Healthy Children.

AMF and SCI will become our ‘High-confidence recommendations’. They have been vetted extensively by GiveWell, and have a high probability of achieving a lot of good with your money.

Project Healthy Children and Deworm the World will be classified as ‘Opportunities for leverage’. There are two reasons to separate them in this way: their projects have not been scrutinised in the same level of detail as AMF and SCI, and by its nature their approach - influencing health policies in developing countries - is harder to concretely evaluate. If successful, both might achieve more good per dollar than AMF and SCI. However, it is hard to know how likely they are to do so.

We are also going to list other organisations such as

- Those we are investigating now

- Copenhagen Consensus Post-MDG project

- We regard this as a very promising opportunity and more information will be forthcoming in the near future.

- AidGrade

- We are writing a short report on AidGrade, and will likely have more to say about them in future as their project matures.

- APOPO

- We are at an early stage, collecting information on the fundamental cost effectiveness of their work.

- Copenhagen Consensus Post-MDG project

- Those we have looked at in the past, and a brief assessment of where we stopped

What does Project Healthy Children do?

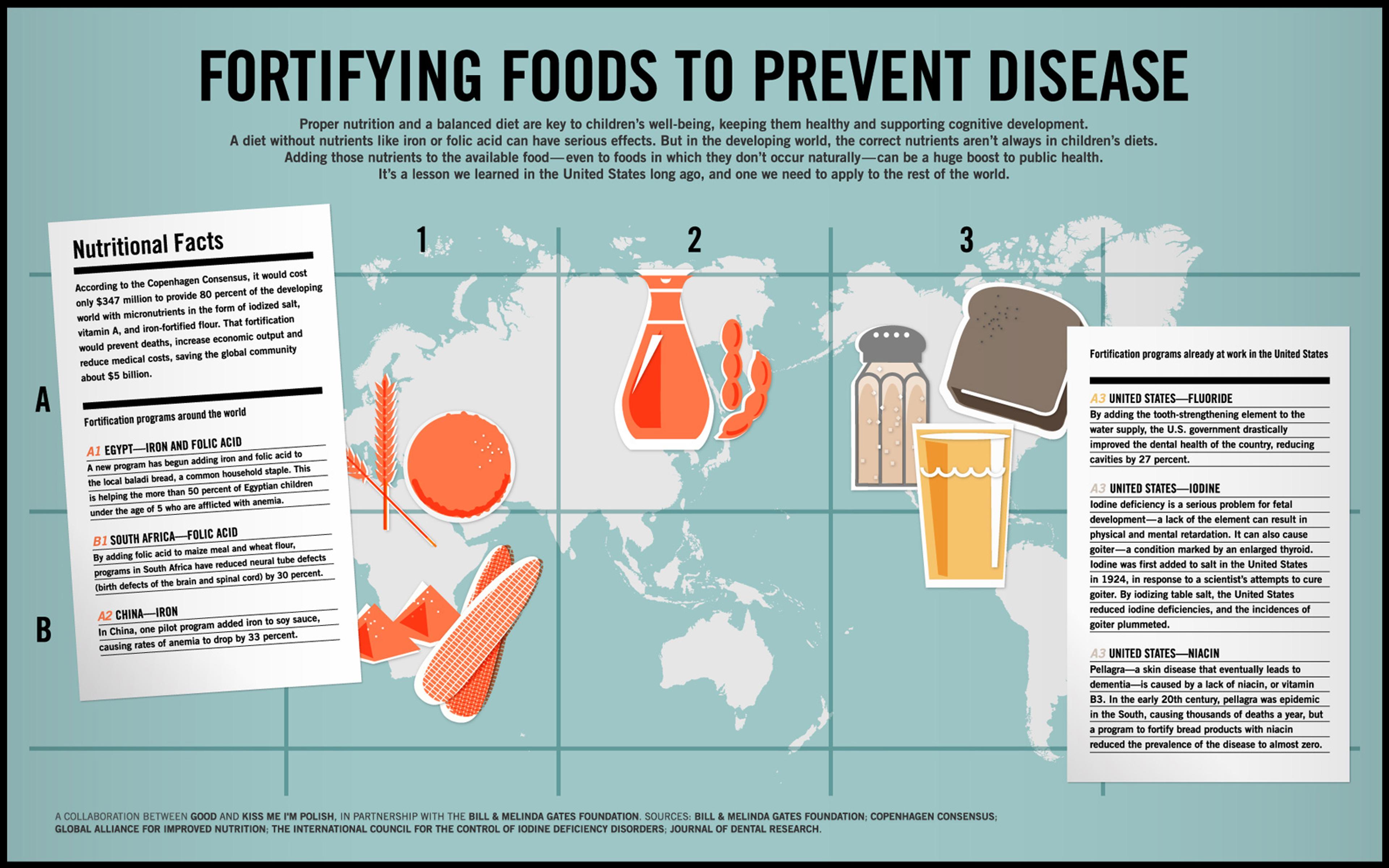

Project Healthy Children sends experts to low-income countries, now exclusively in sub-Saharan Africa, to hasten and increase the quality of mandatory micronutrient fortification of staple foods such as wheat and maize flour, sugar and oil. They place advisors within recipient governments to offer encouragement, coordination across agencies and technical assistance, depending on what is required to push fortification standards forwards.

A significant fraction of people in recipient countries experience worse health due to insufficient intake of iron, vitamin A, iodine, zinc and folic acid. These deficiencies cause the greatest harm in children and pregnant mothers. Ensuring that commonly-consumed foods contain these nutrients should improve population health.

What are some promising things about Project Healthy Children?

- They are promoting an approach - micronutrient fortification of staple foods - that costs very little per person reached, typically under $0.30 per year for ongoing fortification with the most important nutrients. Micronutrient intake is regarded as a top priority health issue for the developing world by the Copenhagen Consensus and the World Health Organisation.

- Increased micronutrient consumption is highly likely to reduce the severity of deficiency.

- They have operated, and probably will continue to operate, in countries with high levels of micronutrient deficiency.

- They operate on a tight budget. A single member of staff lives in each country for 3-6 years and is paid a modest income. This individual, with support from two central staff members in the US, can run a full country program to completion for only a few hundred thousand US dollars.

- If they achieved a comprehensive national mandatory fortification scheme in any given country, this would affect millions of people. The cost to PHC per person reached with fortified foods per year would be in the order of 1 cent.

- We have spoken with four contacts in affected countries who have had dealings with PHC. Their names were provided by a technical fortification expert recommended by PHC. All had a positive view of the competence of PHC staff, felt they were filling a useful gap not filled by other organisations, and were respected and appreciated by recipient governments.

- We have heard that some of the countries PHC has operated in, or are considering opening new offices is, are not yet making progress on food fortification.

- Our qualitative impression from dealing with them is one of overall competence.

- They have described learning from mistakes made in Honduras in the early days of the organisation, and have dramatically shifted approach in response.

- They claim to put a lot of research into deciding in which countries to open offices, weighing up the chances of success and the number of people assisted, among other characteristics. Documents they have sent us appear to back this up.

- As a result of all of the above, their approach could generate big health gains for each dollar they spend. A ‘naive’ cost effectiveness calculation might be as follow:

- $450,000 for a country program

- The country has a population of 10 million

- They have a one in three probability of the program successfully leading to comprehensive iron fortification to combat anemia

- If they succeed, they will bring forward the initiation of fortification by six years

- Iron fortification would on average improve health by 0.3% for each person in the country (source), considering both the level of harm caused by anaemia and its prevalence.

- This leads to an estimated ~$7 per DALY averted, or ~140 DALYs for each $1000. If this were correct, it would be a higher expected impact than AMF or SCI, and obviously be extremely exciting.

- While this is a plausible calculation, I expect that it will turn out to be over-optimistic. Experience shows that the more you learn about an intervention the more likely it is to ‘regress to the mean’, and be less impressive than you initially thought. The question is how much we should adjust back estimates such as this to account for our remaining uncertainty. This is in large part a judgement call, which is why we are putting forward this information so that donors can make their own judgement.

What are your most significant remaining questions about PHC?

- We have not yet scrutinised the literature on how much ill-health is caused by anaemia. GiveWell have suggested that the evidence on this used by the WHO and other groups may not be comprehensive or reliable.

- There are conflicting reports regarding the impact of vitamin A and zinc deficiencies on child health. These may be subject to the ‘decline effect’ where high initial estimates are not replicated in future research. For instance, these two papers - which have been contested - did not replicate the impacts of previous research. Furthermore, progress has been made on vitamin A supplementation and salt iodisation in recent years, so rates of deficiencies may not be as high today as in the past.

- We do not have a clear record of their apparent impact across all of the countries in which they have operated. As such, the positive stories we have heard in Rwanda and Malawi may not be representative. We expect to receive further information about this issue in the near future.

- Larger organisations such as UNICEF, USAID, Hellen Keller and GAIN also work on micronutrient nutrition. Previous successes that appear to be caused by PHC may be in part due to the work of other organisations. However, I would note that PHC has given compelling responses to questions about their overlap with other groups.

- They claim that UNICEF does not do their style of fortification policy work.

- USAID provides funding for programs, but also does not do work on fortification policy with governments.

- GAIN and Helen Keller run more similar projects, but PHC is careful not to open offices where they already have matters covered. GAIN usually focusses on the largest countries, which creates a niche for PHC in providing experts for small, challenging or otherwise neglected countries in need of fortification.

- Note that even where a country would otherwise achieve fortification, PHC can still have impact by increasing the number of nutrients used, the share of the population covered, and the enforcement of the policy.

- We hope to speak with representatives from these organisations in the near future to confirm all of these claims.

Would you personally give to Project Healthy Children on the information we have?

I will be making a donation to PHC for two reasons. One is that I am optimistic they are having a large impact on people’s health. The second is that I hope it will encourage their further involvement with our research. The value of the information we hope to get from them is significant. If they pass further scrutiny they could be a target for large donations from both us and other effectiveness-focussed donors, which would allow them to operate in many more countries which would benefit from fortification.

If you choose to give to PHC, please let us know.

What should influence my decision about whether to give to a low or moderate risk recommendation?

If you prefer a high probability of some impact, or are naturally skeptical about organisations claiming to have a large impact by influencing government policy, then our ‘low-risk recommendations’ will be more appealing to you. If you are particularly persuaded by the material available about PHC and DtW, inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt, and comfortable with variable results, then you will be more inclined to give to those groups.

What are our next research steps?

As described above we are collecting information which will give us a more comprehensive view of PHC’s record of success, will aim to speak with other organisations working on micronutrients, and will scrutinise the evidence used to support high benefit to cost ratios of fortification. Further research could both lead us to endorse PHC with greater confidence, or drop it from our list. Those who would like to know more, or offer relevant information, can reach us at research [at] givingwhatwecan [dot] org.

What is GiveWell’s attitude to Project Healthy Children and Deworm the World?

We asked GiveWell about its views on these organizations. GiveWell responded as follows:

"Both Deworm the World and Project Healthy Children are near the top of the list of organizations we would be interested in considering were they interested in working with us. In both cases, we think there are significant unanswered questions about the organizations' track records that lead us to expect higher impact per dollar from our top 3 charities (AMF, GiveDirectly and SCI) relative to these 2.

We would be interested in evaluating both PHC and DTW if they were ready to go through our charity evaluation process. (In fact, we reached out to both organizations earlier this year suggesting that they engage with us.) In addition, in the case of DTW, we've done considerable work on the evidence for deworming and feel comfortable in our assessment of the evidence. We have only done minimal work on the evidence for the types of nutrition programs that PHC implements and, based on our past experience, we feel that this in-depth assessment of the independent evidence for program effectiveness would also be an important step in any assessment we would make.

We agree that both organizations have the potential for leveraged impact, but we think it's worth noting that there are many other organizations in many different categories about which the same could be said. Within developing-world health, there are many other organizations that seek to leverage government resources (examples include Micronutrient Initiative, GAIN, ICCIDD, and many more) and there are also many organizations that seek to pioneer fundamentally new approaches to old problems, which if adopted widely could have extremely magnified effects (some examples can be found on the Skoll Foundation website). We also believe that our top charities have their own opportunities for magnified/leveraged impact (see the section just below the "strengths/weaknesses table" of our 2012 top charities announcement). More broadly, there are many organizations in many causes that work on policy advocacy, scientific research aimed at technological breakthroughs, field research aimed at better informing aid, systems change, culture change, and other interventions that could have enormous effects from a cost-per-DALY perspective. Donors seeking higher-risk, higher-reward charities have many options."

My response to this would be:

Preferring more strictly vetted charities is a defensible position. Whether you think DtW or PHC can outperform other organisations will be affected by how strongly you assume a charity of this kind doesn’t work until comprehensively proven otherwise. However, given the potential to increase our impact several-fold relative to AMF, I think we should take their approach very seriously both in our further research, and when considering where to give. The risk that PHC turns out to be worse than the alternative has to be balanced against the fact that it could be much better.

While I agree with GiveWell that it is possible that the other organisations listed offer even larger leverage, the research we have done gives us greater confidence in PHC at this point than any of the others listed. The probable existence of other, better, as-yet-unidentified options isn’t relevant for someone deciding between AMF or PHC today.