What you need to know about school-based deworming from SCI

This is the first in a series of posts about the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI), one of our highly-recommended charities. Based in Imperial College, London, they work with a number of African countries to control and eliminate schistosomiasis in regional and national-scale programmes. Clearing an entire country of a disease is no small feat, and a lot of time and effort is spent researching the distribution of the disease and promoting the programme to the population before any drugs are distributed. This is a summary of a presentation given at SCI’s Open Day by Jane Whitton, the Country Programme Manager for Malawi, and describes how a typical project is run.

Schistosomiasis is caused by the two species of Schistosoma worm that live in the blood vessels of either the urinary tract or the intestines and cause anaemia, stunted growth and poorer school performance in children, while chronic infection can cause organ damage, increased risk of HIV infection, and eventually be fatal [1]. People come into contact with worm larvae carried by snails in freshwater sources. Inadequate sanitation and hygiene play a big part in the spread of the disease. As with other worm infections, schistosomiasis is easily treatable with safe drugs (usually praziquantel) and can be controlled by preventative treatment of the population [2]. However as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), it has not been addressed on a large enough scale, and in 2012 only 14% of people in at-risk populations were treated [3].

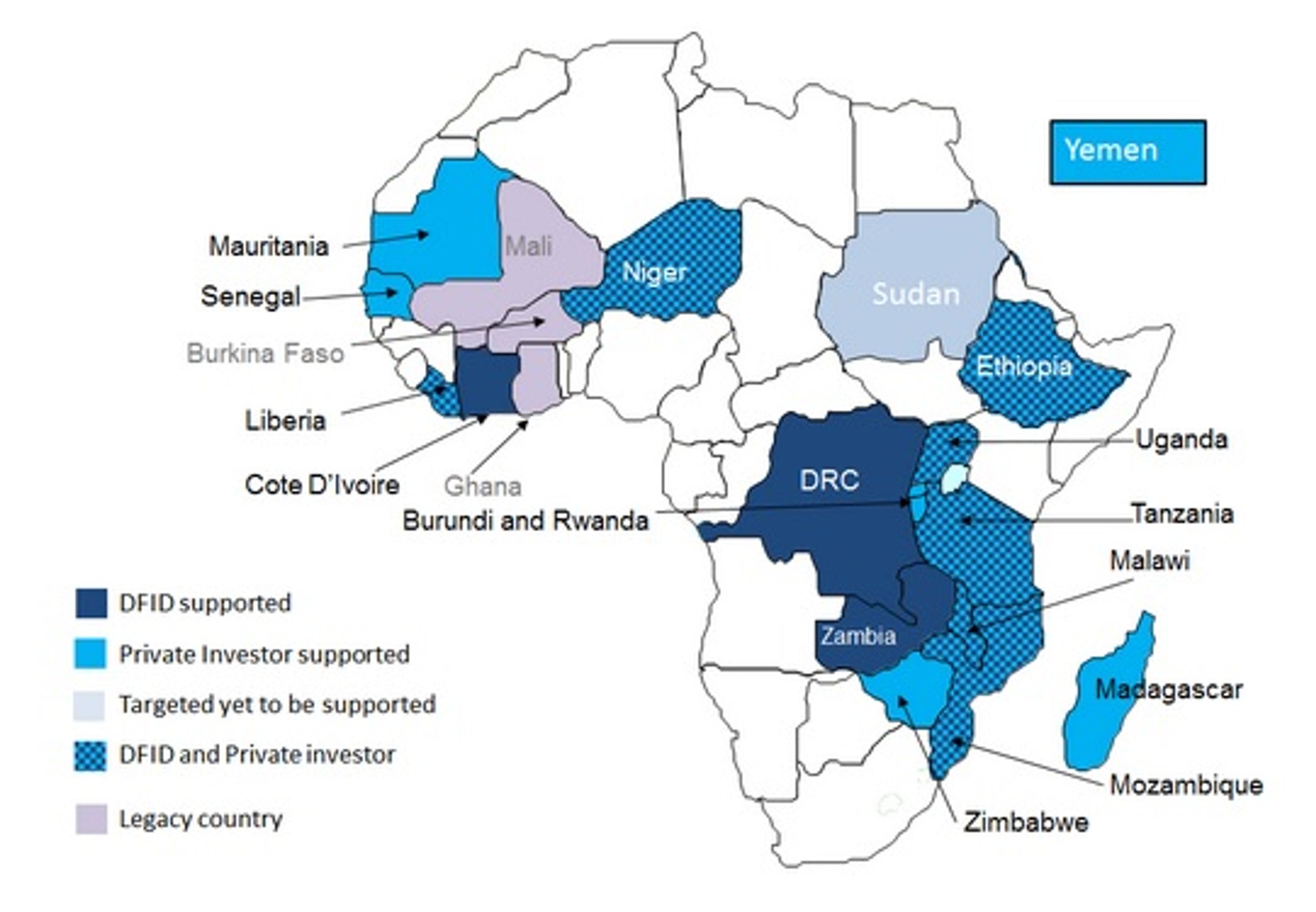

Until 2000, Egypt was the only African country that had a schistosomiasis control programme. The disease was prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, and in 2003, SCI received a donation from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for three years to prove the concept that people could be treated at scale in 6 countries in endemic areas. Following on from this, projects were carried out with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and private donors such as Giving What We Can members. Currently, SCI runs projects in 16 African countries and in Yemen, while in two countries (Mali and Burkina Faso) the projects have been taken over by other organisations and no longer rely on SCI. These have become “legacy countries”.

The length and scope of projects in a given country can vary, depending on how much treatment had taken place before, how much is known about the disease epidemiology in the country, what infrastructure is available for drug delivery and the goals of that specific program. The endemic country needs to be committed to the programme and to provide the necessary resources, which includes putting together a national NTD strategic plan and nominating a focal person to manage the programme e.g. the NTD Programme Manager from the Ministry of Health. SCI works closely with governments to draw up a contract and generate a plan of action, which includes yearly work plans and budgets.

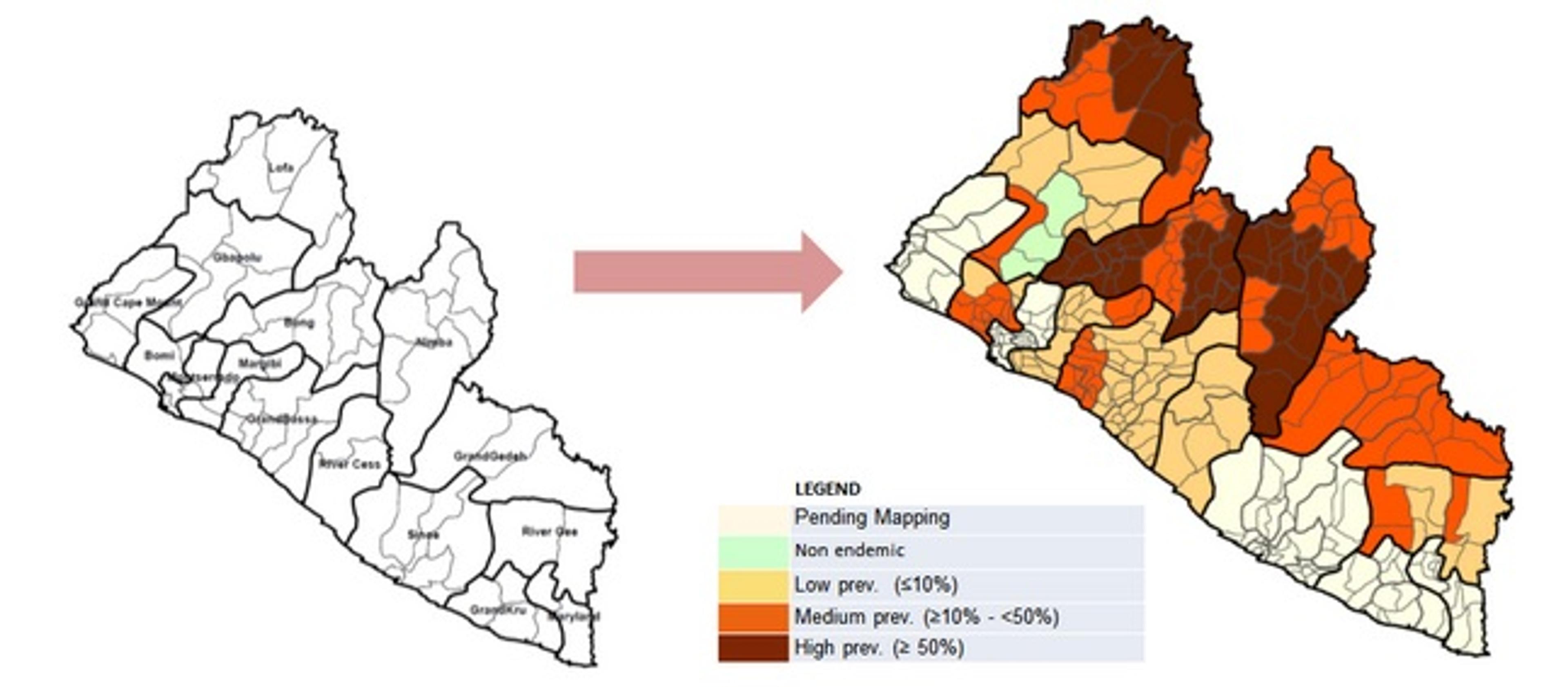

Once plans have been drawn up a less-obvious aspect of a project needs to take place that can nevertheless take a lot of time: mapping the disease prevalence within the country. Often, there would be little or no knowledge of the distribution of schistosomiasis in different regions. Sometimes previous maps are available, and knowledge of geographical factors (e.g. climate, water location) can also give an indication of where schistosomiasis is likely to be found [4]. The survey begins with school testing in a few areas of the country, and several phases of mapping are needed to build up a picture such as the one shown below for Liberia. The prevalence in each region dictates how frequently treatment should be carried out. For areas with over 50% of the population infected, drugs are administered once a year [5], whereas moderate prevalence areas (less than 50% but more than 10% prevalence of infection) treatment once every two years is recommended. In low-prevalence areas (less than 10% of the population) - recommendations are that children be treated twice during their primary-school years.

After the distribution of the disease is established, preparations for treatment can begin. SCI ensures that the target country has enough resources and staff to deliver the medication to all who need it without relying on manpower from abroad (SCI only have one or two people working with each target country!). The drugs are usually administered to children by community health workers or school teachers, who may not be familiar with schistosomiasis and need specialised training. This training is given in a capacity-building cascade, where information on disease biology and programme logistics is passed down from the Ministry of Health to the provincial level, then to the district and finally to the community level. However, capacity building is only half of the challenge: the second stage in the preparation is reaching out to the population and publicising the campaign emphasising the benefits but also giving information on the mild side effects that very occasionally occur. If infected communities are not given enough information, the campaign risks not reaching enough children or poor compliance with the treatment. To avoid this, radio and printed media, community meetings and health days in schools are used to raise awareness of schistosomiasis and the importance of good hygiene in lowering the risk of infection. The capacity-building and social mobilisation prepare the community for treatment and ensure that everybody is clear about their roles and expectations.

Weeks before the treatment, drugs and equipment are delivered to the target country. This is done in advance to allow distribution of drugs to all communities, including hard-to-reach ones. The storage of the drugs are monitored to ensure that the medications are distributed on a first-in, first-out basis and do not pass their use-by date. On certain days, after a well-publicised campaign, the drugs are administered to children in schools.

Although it may seem that after population treatment the project is finished, but the story doesn’t end here. At every step of the way, monitoring and evaluation takes place to assess how well the programme is working and what factors influence its success, which in turn allows improvements to be made. SCI also reports its findings both to the local communities and to donors. In fact, monitoring and evaluation is so important that 10% of SCI’s funds are dedicated to it [6]. The process can be divided into the three categories:

Process monitoring

This ensures that every stage of drug delivery, personnel training and mobilisation is timely and correct, the training is carried out to a high enough standard, and enough people are reached in sensitisation/mobilisation campaigns.

Performance monitoring

This analyses the treatment coverage, i.e. how many people actually received the drugs. SCI aims for at least 75% coverage of school-age children, a target set by the World Health Organisation and household surveys are carried out to confirm the numbers. This is also an opportunity to identify regions with low coverage and see how this can be improved in the future. People involved in drug administration (such as teachers and community workers) are interviewed to assess their knowledge and attitudes, and assist in finding out why the drugs are not reaching enough people.

Impact monitoring

This is to show the impact of the programme on reducing the morbidity of infection. For this, longitudinal cohort studies are set up to monitor children before and after each round of treatment, as well as untreated children for comparison. Some of the factors analysed are: number of parasite eggs present in urine and faeces (dependent on species), health indicators such as anaemia and presence of blood in urine, and also the quality of sanitation in the community. To give an example, combination treatment of nearly 2000 children in Uganda with praziquantel and albendazole led to an 82% reduction in Schistosoma infection after two years [7].

This overview should give an idea of the efforts that go into a schistosomiasis control and elimination projects. Although we might think it’s as simple as giving medication to children, a huge body of behind-the-scenes work - planning, communications, monitoring - is necessary to make it happen. SCI has already carried out successful projects in a number of African countries, but a question remains: is it possible to eradicate schistosomiasis entirely? This will be the topic of the next SCI blog.

References

- WHO: Schistosomiasis

- WHO: 10 Facts about Schistosomiasis

- WHO: Media Centre

- Imperial College London: Schistosomiasis Control Initiative Mapping

- WHO: Helminth Control in School-Age Children

- Imperial College London: Schistosomiasis Control Initiative Monitoring and Evaluation Slides from Jane Whitton’s and Prof. Alan Fenwick’s talks at the SCI Open Day 2014

- Kabatereine NB, Brooker S, Koukounari A, et al. Impact of a National Helminth Control Programme on Infection and Morbidity in Ugandan Schoolchildren. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(2):91-99