This is a follow-up on the post The Economics of Morality.

Overcoming Economic Biases

When people invest in the stock market, their primary goal is to make as much money as possible. We know this because a massive industry has grown to ensure that stock investments yield optimal returns, stocks which yield poor returns quickly die out, and investors explicitly consider it their fiduciary duty to maximize profit for shareholders. When people give money to charity, or formulate opinions on how their tax dollars ought to be spent, their primary goal is not to help as many people as possible. We know this because only a tiny fraction of donors have even heard of organizations like The Life You Can Save, ineffective charities thrive alongside charities which are more effective by orders of magnitude, and people rarely seem to consider the size of the impact of their philanthropy.

There are many biases which hinder our efforts to make optimal economic decisions, such as the gambler’s fallacy or loss aversion. And when it comes to our fiscal health, we recognize that these biases are bad. We understand that, for example, having a successful fund for your child’s college education depends on overcoming psychological mechanisms favoring impulsive spending. As we’ve seen, there are also manifold biases that prevent us from making altruistic decisions effectively. But when it comes to our moral decisions, people often fail to see these biases as in any way problematic. Most importantly, people fail to appreciate that the fate of billions of people in the world today - and potentially the entire future of humanity - depends on us finding a way to overcome our moral biases.

As humans, we tend to underestimate the value of rewards and punishments based on how far into the future they will occur. This bias is known as ‘hyperbolic temporal discounting’[1]. For instance, people will often prefer a smaller, more immediate sum of cash to a larger sum of money which they will receive at some point in the future. This is an obvious impediment to certain financial goals, like saving for retirement. Yet, in spite of temporal discounting, many people somehow succeed in long-term monetary planning.

Perhaps people who are fiscally prudent are immune to temporal discounting? But no, this hypothesis is not borne out by the psychological literature. Rather, the conflict between immediate and delayed gratification involves two somewhat independent cognitive processes[2]. One - the fast, emotionally charged process - generates a strong visceral desire for immediate reward. The other - the slower, emotionally cooler process - responds to abstract reasons. Things such as saving for retirement require our slower, reasoning processes to direct or perhaps supersede our faster, intuitive processes.

Despite the fact that our economic decisions are plagued by biases, to a large extent we have learned to prevail over them. We’ve done this by explicitly evaluating our economic activity in terms of monetary yield. Having this aim allows us to make economic decisions empirically and rationally, rather than by relying solely on what intuitively strikes us as the correct way to invest our capital. I suggest that we should take these lessons from economics and apply them morality.

Overcoming Moral Biases

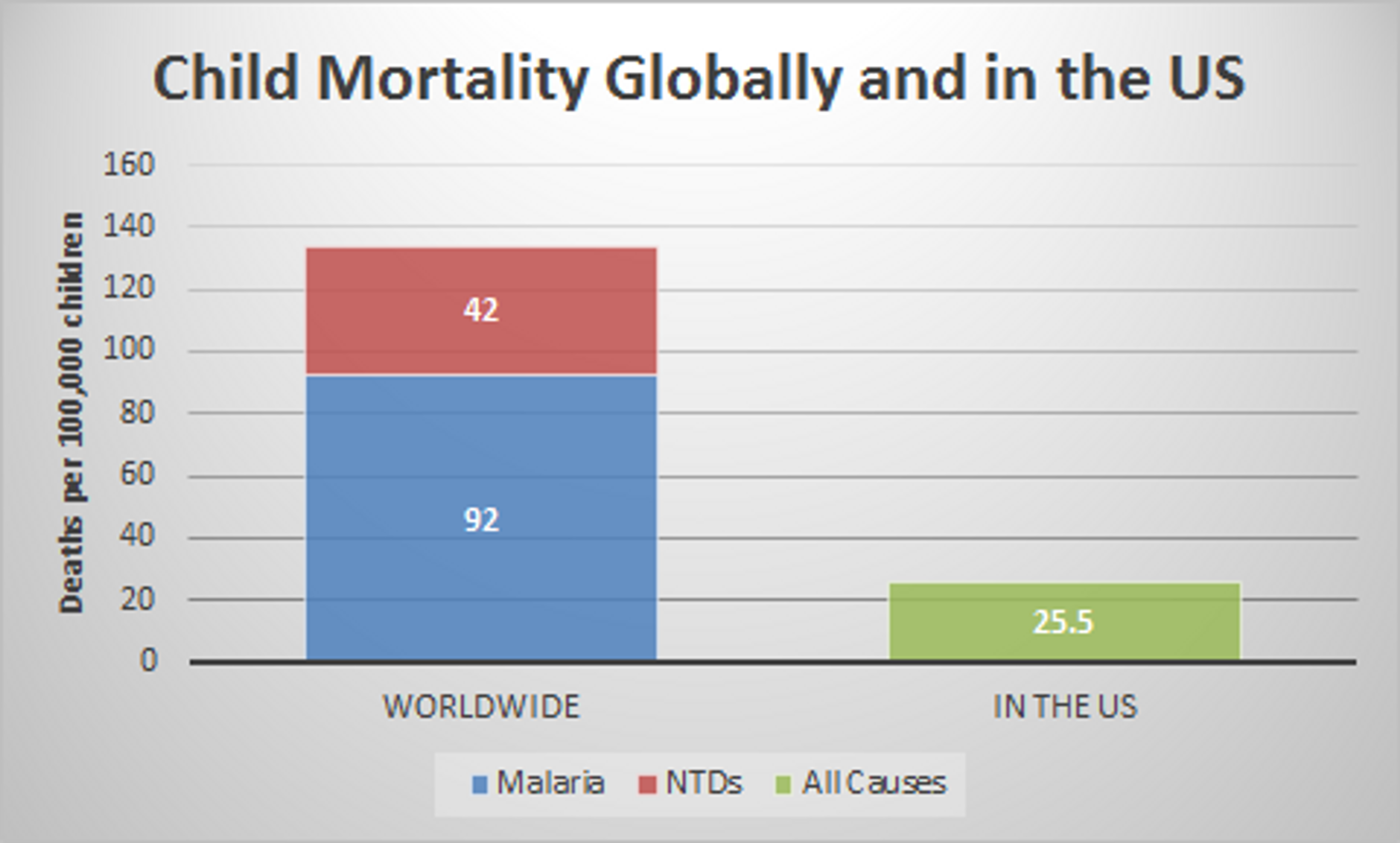

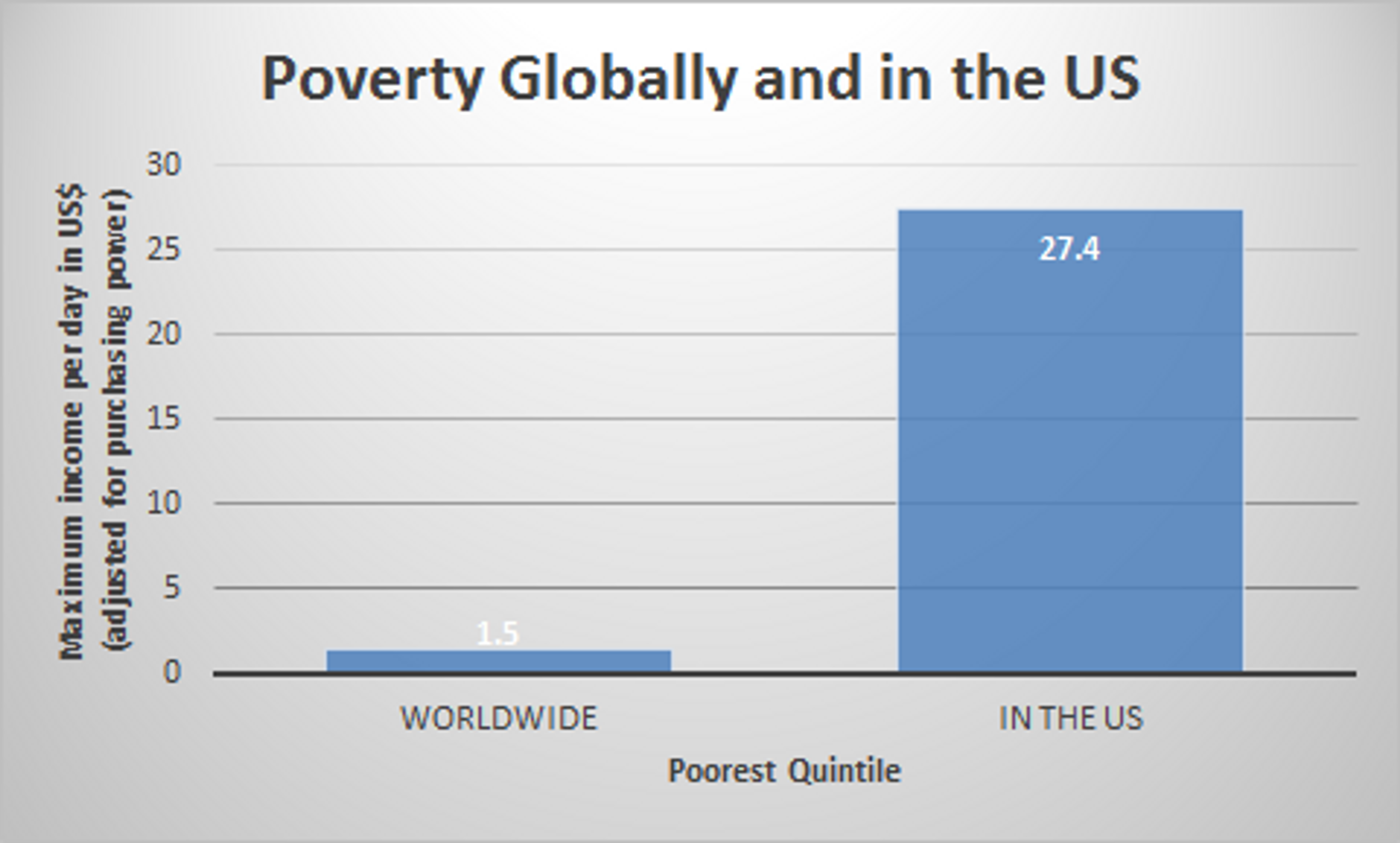

Extreme poverty could be eliminated for $330 billion annually[3]. Malaria and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) could be permanently eradicated for $10 billion full stop[4]. This may sound expensive, but the costs of these projects could be paid for by the US and EU for less than 1% of their GDP[5]. Lest there be any doubt about the severity of these problems, consider that the poorest quintile of the global population is 20 times as destitute as the poorest quintile of the American population[6]. And children worldwide are being killed by malaria and NTDs at 5 times the rate that children die in the USA from all causes combined [7].

These problems are both more terrible and far easier to fix than most people understand. Yet the billions of people affected by them will continue to subsist in an incomprehensible depth of misery as long as we in the developed world fail to act. But they live far away from us. They are not of the same skin color as many of us. They are not citizens of our countries. We don’t see their faces or know their stories. And so we let them suffer and die.

As ineffective altruists, our potential for helping others is stifled by our moral biases. Charities and public policies gain support not based on the extent to which they improve the lives of conscious creatures, but based on the force with which they pull on our heartstrings. Hopefully the catastrophic consequences of the status quo have convinced you that we need to revolutionize how we think about morality. In addition to thinking emotionally, we need to think economically. Altruism should be explicitly viewed as an investment in the well-being of conscious creatures. And we should demand nothing less of ourselves than to see our investment yield maximum returns.

Adopting this attitude will turn us into effective altruists. At a minimum, effective altruism says that to the extent we care about the well-being of others, we should try to improve the lives of as many people as possible by as much as possible. You don’t have to be a thoroughgoing utilitarian to accept this premise. For example, you don’t have to be willing to push fat people off footbridges or harvest your patients’ organs to be an effective altruist. All you have to believe is that it’s better to give more help to more people, rather than less help to fewer people.

And again, I want to emphasize that my argument is not necessarily that you should value all individuals equally. My point is simply that you shouldn’t value some individuals more than others based on obviously morally unimportant factors, like race, sexual orientation, nationality, or physical proximity. You are probably already devoting some portion of your time and money to helping people who are not your family, friends, or community members. So why not try to use this time and money to improve the well-being of conscious creatures by as much as you possibly can?

Once we accept that the purpose of altruism should be to eliminate as much suffering as we can, the question of where we should donate to charity or how our tax dollars should be appropriated is no longer a matter of opinion, but a matter of fact. Empathy may drive us, but reason and evidence need to steer us. This is the key to discovering and overcoming our moral biases. We need to recognize the immense amount of suffering in the world today, as well as the vast potential for happiness in the future, and take it as our mission to make the world as happy a place as it can possibly be.

Whatever Next?

Suppose you’re ready to think of your charitable donations in economic terms - as an investment in the well-being of conscious creatures. What are you to do next? You could attempt to systematically evaluate every charity in the world in terms of cost-effectiveness, but I would advise against it. Analogously, individual stock investors cannot reasonably be expected to create their own portfolios. We rely on experts - stock brokers - to gather this information for us. Similarly, several charity evaluation organizations review charities based on proven records of cost-effectiveness. There is none better than GiveWell.

If you find yourself prepared to make an even greater commitment, consider increasing the amount of money you donate to effective charities. Until everyone can give more effectively, we need those who are giving effectively to give more. Over 1,000 people have pledged to donate at least a tenth of their income effectively. Consider taking the pledge with us at Giving What We Can.

Should you find yourself even more inspired, you may want to consider effective career paths. Work for an effective charity, or attempt to start one of your own. Consider a career in politics, campaigning to devote more resources to foreign aid, and to make sure these resources are used effectively. Or perhaps take a high-paying job. The more you earn, the more you can donate. Learn more with 80,000 Hours.

References

- Green, L., Fry, A. F., & Myerson, J. (1994). Discounting of delayed rewards: A lifespan comparison. Psychological Science, 5, 33-36.; Madden, G. J., Begotka, A. M., Raiff, B. R., & Kastern L. L. (2003). Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11, 139-145.

- Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106, 3-19.; McClure, S. M., Laibson, D. I., Loewenstein, G., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science, 306, 503-507.

- Extreme poverty is defined as living on less than $1.50 a day. Currently, 1.2 billion people worldwide live in extreme poverty. Calculation assumes the income of those in extreme poverty is distributed normally.

- Zelman 2014 (Zelman B, Kiszewski A, Cotter C, Liu J (2014) Costs of Eliminating Malaria and the Impact of the Global Fund in 34 Countries. PLoS ONE 9(12): e115714. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115714) estimates the cost of eradicating malaria at $8.5 billion. Data from the WHO compiled by O’Brien 2008-2009 (O'Brien, Stephen, comp. "Neglected Tropical Diseases." (2008-2009): n. pag.World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Web. 17 Jan. ), p.13 puts the cost of eliminated NTDs at $1.4 billion.

- In 2013, the GDP of the US was $16,768,100 million, and the GDP of the EU was $17,958,073 million (World Bank. "World Development Indicators." Data: The World Bank. The World Bank, n.d. Web. 15 Jan. 2015.0).

- More precisely, the poorest 19% of Americans live on less than $27.40 a day (United States Census Bureau. "Annual Population Estimates." State Totals: Vintage 2011. United States Census, n.d. Web. 19 Jan. 2015. ). The poorest 17% of the world’s population live on less than $1.50 a day, meaning they are 18 times as destitute. Dollar amounts adjusted for purchasing power. Calculations assume income is flat or normally distributed.

- According to the CDC, 25.5 children per 100,000 US children die each year. Child mortality for NTDs is estimated from data gathered by the End Fund (End Fund, The. "NTD Overview." NTD Overview. The End Fund, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2015. ). Of the 1.5 billion infected with NTDs, 800 million are children. 500,000 people will die from NTDs per year, so assuming NTDs are equally lethal for all age groups, 270,000 of those who die will be children. WHO estimates that 584,000 children die from malaria each year. Given that there are 633 million children in the world (British Association for Child and Pediatric Health), the global death rates are 42 for NTDs and 92 for malaria.