Every time you choose to donate to a particular charity you're choosing a particular problem which you want to address. But the menu of problems that you choose from isn't fixed. What gets onto that menu and, to stretch the analogy, how each item is described, can change over time. In other words, you can change what we define as problems and how we define them. In this post I explore that idea and why it's so important.

Intuitively it may seem that there are many problems in the world ready to be found. We don't have to go looking for them – they're just there. We might think in very general terms of poverty, disease, inequality, or discrimination.

There's another way of thinking about these problems, though. And that is to say that no problems just 'exist', awaiting discovery and resolution. Instead, they are constructed by us. We look at the things happening in the world, decide to label some of those things as problematic, and set out to do something about them. There's nothing inherent to those things that makes them problems apart from our thoughts about them.

One of the key things, of course, is who that 'we' is. Different groups of people recognise different things as problematic, leading to different political or charitable priorities. And those priorities change over time as well. Not many people thought slavery was a problem before the 18th century; nowadays very few would defend it.

This is important, because influencing what circumstances are seen as problematic and in what ways can be a very effective way of bringing about social change.

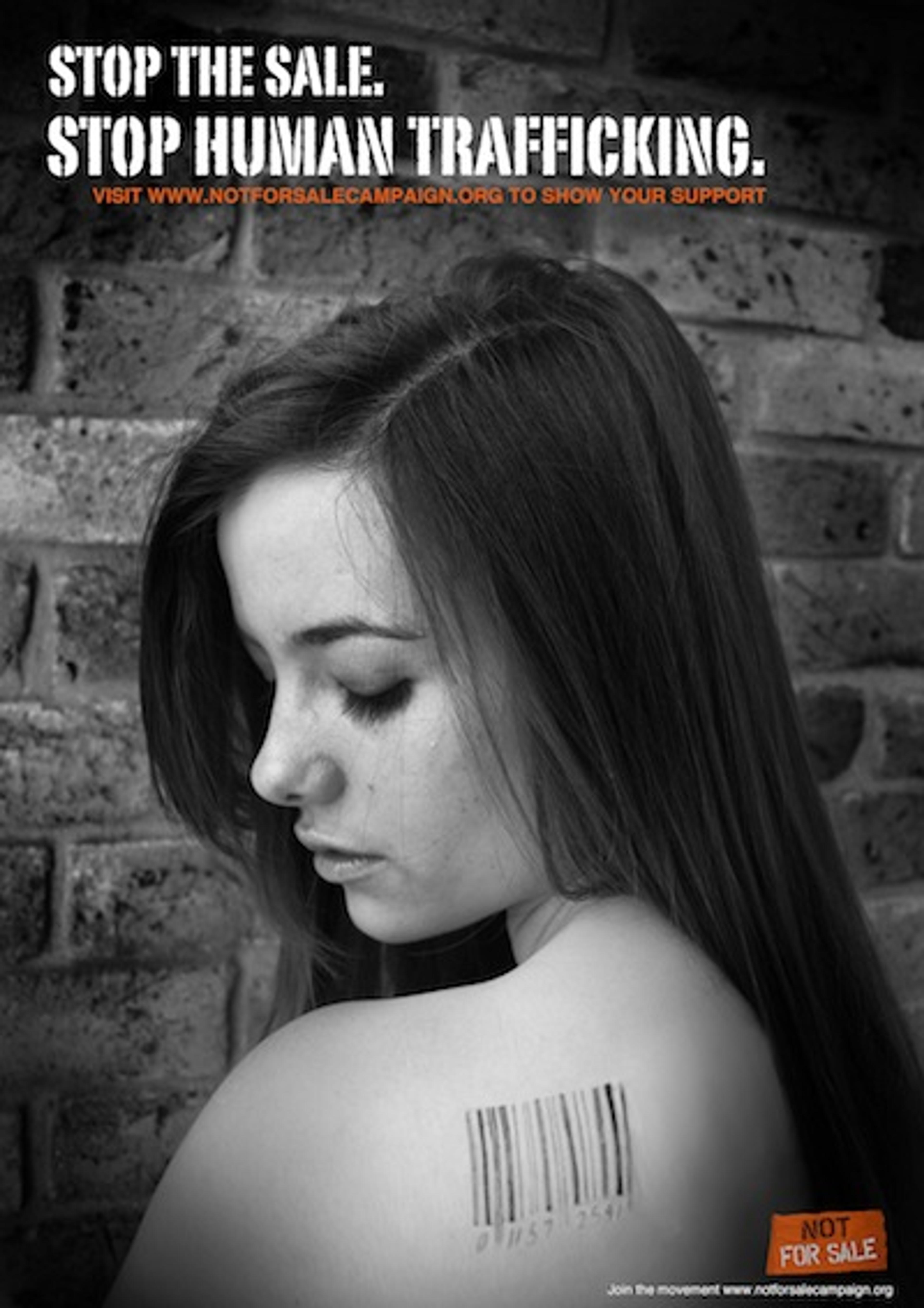

A good example of a problem where we can see the process of construction in action is human trafficking, the subject of my own research. In the middle of the 20th century, it was rarely spoken about, but it became more prominent through the 1980s and 1990s. This history of the approach to human trafficking is a good example of how, if enough people are persuaded that an issue is problematic, it can become a policy priority and start to attract attention and resources.

Source: Not for sale campaign

When trafficking initially become prominent, it was largely thought of in gendered terms – as the trafficking of women and girls for sexual exploitation. More recently, since around 2000, that model has started to change and there has been a move towards seeing it as including, for example, the movement of men and boys into other kinds of exploitative practices such as agricultural labour, drug cultivation and street begging.

So it's not just a matter of recognising a problem that hasn't previously been talked about; the way we see that problem can change as well. The actual practices thought of as constituting human trafficking have changed substantially over time.

The same is true for the way the problem is framed more broadly. In the UK and elsewhere it was initially seen as essentially a problem of illegal immigration. The UN Protocol established to deal with trafficking in 2000 reflected that idea.

Yet other framings have subsequently become more prominent. The Council of Europe and the European Union (in its more recent Directives) have emphasised the human rights aspects of trafficking. More recently still, in the UK, the language of 'modern slavery' has become influential and some have started to talk about trafficking as an issue exploitation, with the movement element much less important.

These different framings share a common conception of the kind of practices thought to constitute trafficking but (while certainly not mutually exclusive) they place emphasis on very different aspects of the problem.

So human trafficking is an example of a problem where a set of circumstances not initially the subject of much policy or charity activity became widely perceived as a problem needing to be tackled. Once that had occurred, what was meant by 'human trafficking' rapidly changed its shape, and so did the broader framing of the problem.

This is potentially very important. Gaining recognition for a problem not previously talked about is obviously influential. However, changing the way a problem is constructed or framed can also have important effects. When we change how we think of a problem we change what we do to address it – what resources are allocated, by whom, for what purposes, etc.

In terms of framings, if human trafficking is fundamentally an issue of illegal immigration then the logical steps to take in order to address it involve tougher border controls and perhaps changes to the asylum system or visa allowances. If, on the other hand, it is basically about protecting the rights of victims then we need to establish mechanisms to identify those victims and offer them support. The lens through which we view the problem has important implications for what we do about it.

What about other problems?

All this is open to the objection that human trafficking is basically a social problem, i.e. a messy, people-centred kind of an issue where data are lacking and it's entirely possible to have lots of competing perspectives on what it involves, why it is problematic, etc. What about problems which belong more in the realm of hard science, like disease? Surely it doesn't matter how you 'construct' an illness – it remains something very tangible with known effects and cures.

Even in relation to disease, however, the way we construct problems matters enormously. It affects both the priority we give to different diseases and also how we deal with each one. When it comes to priority, the recent trajectory of ALS (following the 'ice bucket' campaign) is a good demonstration of how a change in profile can affect the attention and resources made available to address a problem.

We can also change the way we construct or frame a particular disease. HIV/AIDS is a good example. Stigma against the disease has often derived from inappropriate fear of casual transmission or prejudice against groups that are disproportionately affected, such as intravenous drug users and homosexual men. That stigma has at times led to individuals not getting themselves tested or not revealing their illness for fear of discrimination. It also led to support for restrictive policies considered by some to threaten sufferers’ human rights. Changing the way in which HIV/AIDS sufferers are perceived can therefore make a big difference in how resources are allocated without any change in the basic science.[1]

What are some implications of this perspective?

Getting problems recognised as problems is the first step to tackling them. Changing what the public, politicians and charities think of as priorities alters the way resources are distributed – away from some areas and towards others. In some ways this is one of the most profound elements of a democratic society – the collective definition of social problems through public debate. Once problems have been identified, there is significant scope for shaping how they are conceptualised and consequently what is done about them. Problem recognition and construction can be very difficult processes to quantify, but they can also represent two particularly powerful ways through which to bring about social change.