Is private soap squeaky clean? A look at the potential effectiveness of corporate handwashing promotion

Giving What We Can’s mission statement, staring at me from the wall of our office as I write this, is to “move money to the world’s most effective charities”. Working out what these are though can be tricky, as us at the research team have found out over the past week in delving into the literature of schemes involving Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH). We found some broad conclusions:

- Handwashing promotion programs (teaching people the importance of using soap properly) compare very favourably to our recommended interventions (in terms of $/DALY).

- There is not much data relating to the success of WASH schemes, and the methodology is weak, hence at present we will not recommend charities to the same extent as our present top two.

- However, soap manufacturers are in a position, unique to this sector, to fund handwashing campaigns in a manner that benefits both themselves (in profits) and society (in increasing health).

Wanted: Preachers of Soap

Washing your hands can make you both happy and healthy.

In most instances diarrhoea is caused by consuming bacterial contaminants, often through fingers or food. Washing hands with soap at important periods of the day (such as after defecation and before eating) removes these contaminants from the surface of the skin, cutting the risk of diarrhoeal disease by 40-50% (Curtis and Cairncross, 2003).

However, rates of handwashing with soap (HWWS) are low. This is not caused by a lack of (clean) water, or indeed a lack of soap. Rather, the soap available is used to wash clothes and not hands (Aunger et al, 2010). Therefore what is required prevent the disease are education schemes that encourage behavioural and attitude changes towards soap.

Tip-toeing into the Pool of Private Public Partnerships...

Traditionally donor funded NGO programmes, such as Charity Water and Water Aid, provide these schemes, often in combination with infrastructural improvements. The (too) few studies that exist on standalone schemes have been shown in some places, to be very successful.

I wish to stress that private companies which have both a financial and PR incentive, can implement schemes which have the same, if not better results. Unilever is one of these companies, whose Lifebuoy soap brand has the potential to be well publicised and used across the world.

Buoyed by some good evidence

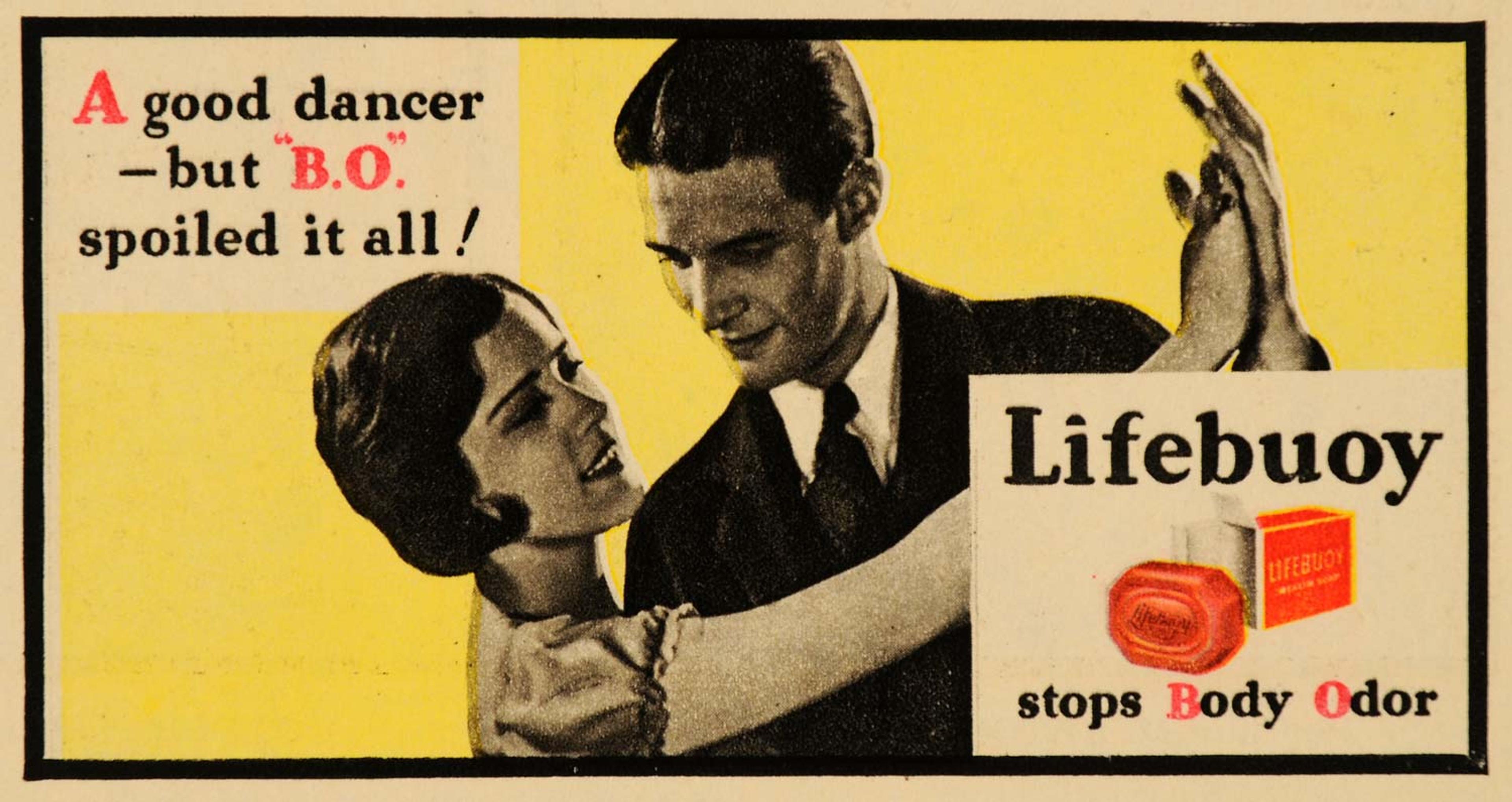

It worked in the past. Could similar adverts eradicate diarrhea in the developing world?

The Lifebuoy soap brand began in Victorian England and is known in North America for its adverts which invented body odour. Its focus is now on the developing world where it is one of Unilever’s top selling products, bought from markets in Ghana to travelling saleswomen in India. In its 2012 social mission report, the brand states its main aim: “to change the hygiene behaviour of one billion consumers across Asia, Africa and Latin America, by promoting the benefits of handwashing with soap at key occasions”. At present, no NGO lists this as a single aim. Though we are cautious, given that too often big businesses say one thing, but do another (for example Coca Cola’ climate change campaign in contradiction to its relation to water consumption in India), there are two reasons to be optimistic about their strategies in relation to the wider WASH sector.

First, their focus on cost-effectiveness. Giving What We Can’s take on the charity sector is to treat donations in a similar way to business investment, a facet which has come under criticism but which we wholeheartedly defend. Just like its advertising campaigns, the promotion schemes are designed to get the largest impact for the money the company invests in. It makes sense in a competitive market. When Unilever saw that by working with governments, local NGOs and schools to “train the trainers”, it saved the company funds but delivered equal results in Indonesia, it sought to extend the scheme to other countries.

Second, Lifebuoy appears to collect good evidence on the impact of its schemes. This kind of self evaluation is what we want to see all charities doing on a regular basis. The Lifebuoy brand has conducted its own Randomised Control Trial in Mumbai, keeps sales data on its soaps through consumer surveys, and are even developing three dimensional sensors in some of their soaps to monitor their use, a method which, due to its unobtrusive nature, is perhaps more accurate than the current norm of participant observation (Vindigni et al, 2011).

Could privatisation save lives?

It will be good to see more transparency in Unilever’s data. Their website does not show, or may not have, these evidence reports mentioned above. If Giving What We Can are going to support schemes such as this, being able to see the data and analysing it for ourselves is crucial. Perhaps this is where the private sector collides with the public sector, as companies are notoriously secretive about releasing knowledge which may provide a competitor a route into the market.

We would also like to see the company investing more money on these schemes. Unilever funds are diverted away from the Lifebuoy schemes to other brands, which add less health benefits to the world. There is a growing market for soap in Africa and Asia, and potential for lots of money to be made, although the risks at present seem to be too great for the soap companies to invest.

Money for (new) soap? Large companies must be persuaded that there is large enough demand for soap in developing countries such as India to make investment worthwhile.

An advocacy organisation could therefore be needed who can show and persuade private companies to divert funds to the developing world. Currently I do not know of any group which does this, but please get in contact or add a comment below. There is an urgent need for more hygiene promotion schemes, and with the funds, knowledge and incentive of private companies, these can be successfully run without donations. Hopefully I have shown you that this change can be realistically achieved surprisingly soon. Part of the solution of moving money to the world’s most effective charities may well be putting more power to the world’s most effective companies.

Citations:

- Aunger et al, 2010: “Three kinds of psychological determinants for hand-washing behaviour in Kenya” Social Science & Medicine 70 (pp 383-391).

- Curtis and Cairncross, 2003: Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 3(5): 275–81.

- DCP2 Report. Cairncross, Valdmanis (2006) “Water supply, sanitation, and hygiene promotion” In: Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (2nd Edition). New York: Oxford University Press. 771-792

- DfID, 2013: “Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Evidence paper” Department for International Development May 2013.

- Vindigni et al, 2011: “Systematic review: handwashing behaviour in low- to middle-income countries: outcome measures and behaviour maintenance” Tropical Medicine and International Health 16(4) pp 466-477

- WHO fact sheet no.330