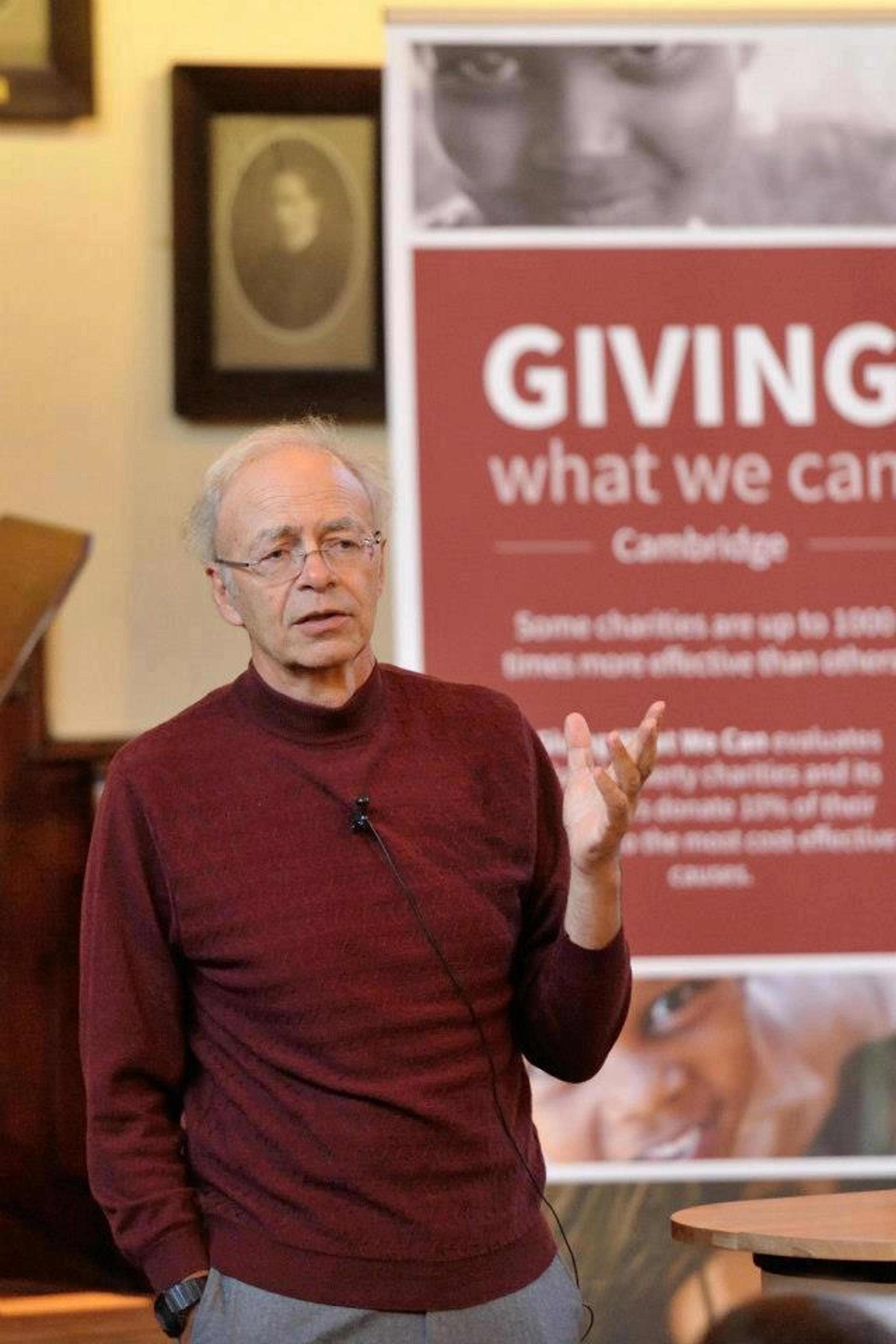

In early May, Peter Singer visited Cambridge to give a talk on effective altruism and Giving What We Can at the Cambridge Union. Before the talk, a team from Giving What We Can Cambridge took the opportunity to discuss effective altruism and effective careers with Professor Singer. In the first part of the interview, published below, Singer answers questions on giving and altruism.

Effective Altruism and some of the key questions behind it…

GWWC: How would you see the relationship between effectiveness and altruism? Where would you place an emphasis? Do you see them as being equally important?

Peter Singer: They are both important. I think really what I'm interested in is the impact that we end up having on problems that need to be dealt with, let's say particularly the issue of global poverty. So it's like saying: if what you're interested in is how much water you get into a bucket then it depends on how wide or narrow the stream is as well as the force, the pressure, with which the water is coming out. You want altruism because that will mean that people do more, but you want it to be effective because that will mean it will have a bigger impact.

GWWC: In a nutshell, what is wrong with the morality exhibited by most people, and what is your alternative?

Peter Singer: What is wrong with it is that people tend to look predominantly at what they actually do as determining right or wrong rather than what they omit to do. Very often when we allow things to happen that we could have prevented, the consequences might be much more serious than infractions to moral rules that people take quite seriously. So I think that our attitude towards morality, to what is involved in living well, is warped by too much of a distinction between acts and omissions.

GWWC: In your experience do you think it's easier to get currently effective people to be more altruistic, or currently altruistic people to be more effective?

Peter Singer: That's a good question but I don't know the answer. I think it varies with the individual person - it will depend on who they are. You can also ask about people who are not presently altruistic - trying to make them altruistic is another step that's very important. Different people are moved by different things: Some people will be moved by how great the need is and how easy it is to have a large impact. Toby Ord tells the story of how he decided to get involved in Giving What We Can and 80,000 Hours by calculating what he would make over his academic career and how much he needed to live on. He then realized that the remaining money could prevent 80,000 cases of blindness. Some people when they realize this will be motivated enough to become effective altruists. Other people will say "well I don't really care; I don't know these 80,000 people, whoever they are". Then I think it is a matter of connecting it with something they do care about. Most people want to feel that their life is fulfilling and satisfying and that they will be able to look back on it and feel that they made good choices. Contributing to something larger than oneself is one way of achieving this.

GWWC: Do you think that the current concept of charity is misguided with its implications of generosity?

Peter Singer: The implication that I think is somewhat misguided is the idea that it's optional because it's charity; it's not an obligation in any way. This strikes me as a problem. Assuming that you're in the category that has an 'adequate' income then effective giving is an essential part of an ethical life, as essential as not violating the 'thou shalt not murder' principle or other fundamental principles.

GWWC: So if it's not about optional giving to 'buckets and collectors on the street', what is enough altruism in your opinion?

Peter Singer: For me there's an ideal level beyond which you wouldn't really want anyone to go and that's a very extreme level given that we have so much and that there are people in such need. That would be a level at which you can't do any more good by giving more. You might not be in the same condition as the people you're helping, but it might be that you wouldn't be able to hold down a job if you were to give more because you need to have decent clothes to wear, or you need a car to get around. This would be a stopping point where if you gave more you'd actually end up giving less.

GWWC: One of the things that characterizes effective altruism as opposed to conventional views of charity is an emphasis on rationality. Are there potential dangers of an over-emphasis on rationality?

Peter Singer: It is always possible to get carried away with reasoning I suppose and to lose track of what people are like and how they are going to respond. That's the kind of thing that I want to guard against when I say that we should try and set a standard that is achievable for most people. If you are purely following the logical implications of the position you would say: "well it's wrong to spend more on yourself or your children or a sick relative, rather than to give it to where it's most effective". But what I suggest is that we try and get people to do something that is effective without being too critical of them if they don't go the whole way. We must have a morality that is tailored to the way people are and not just to 'rational' beings. Giving What We Can takes the 10% standard as part of the pledge; in my book the Life You Can Save and on the website I set up of the same title there's a somewhat different standard which starts off lower and ends up higher depending on how much you earn. What we want to do is make sure that people are aware of the issue, are aware of their obligations, and are committed to doing something significant towards it. Hopefully, once you get people doing something significant they find it actually not that difficult, in fact they will find it rewarding, and then they can work their way up to something more.

GWWC: Do you think there's a risk that if the aim is to try and get people to be more altruistic, by confronting them with the notion of effectiveness, you also confront them with the notion of ineffectiveness which may actually decrease giving?

Peter Singer: There's a worry about how rigorously you maintain this standard of effectiveness. There is a concern that when people go to GiveWell one of the first things they see is this pie chart which says that they've evaluated hundreds of charities and there's only this thin sliver, or 1% of charities as they say, that they've ranked as highly effective. It's natural for people to get the idea that '99% of charities are not effective', but that's not what GiveWell is saying. I've been in discussions with them and I think they've made it a little clearer now that what they are saying is that these other charities have not been able to demonstrate to their satisfaction that they are effective. They may well be effective and may well be as effective as the ones that they do rank, it's just they may be doing work of the kind where you can't perform randomized controlled trials, or where in other ways it's harder to get a handle on how much they contributed to the solution of the problem as against other factors.

GWWC: To stay with the problems of effectiveness, when you allocate money to charities and you try to do it in an effective way, often it involves a decision not just for an effective charity but also against an ineffective charity, and I was wondering where you think one has to draw the line between the heart and the brain? So for example, a charitable intervention for, say, a relative, for a medical intervention, is probably a lot less effective in financial terms than giving to charity. But what reason do we have to prioritise a relative or someone we know over the many people that we could help by giving money to a more effective charity?

Peter Singer: I think we're impelled to help relatives by strong bonds that we have, strong attachments, which essentially are emotional rather than rational. So you asked what reason we have - I think ultimately we don't have a reason, we simply have… this is the way we are, this is what we want to do, and we're following that kind of inclination. I would see this as quite separate from the sorts of things that one does when one acts as an effective altruist. Which is not to say that you shouldn't help relatives, but just to say that helping relatives is on the spectrum of things like treating yourself to a good meal at a restaurant or something similar. There's a spectrum that goes from that to helping the relative who is ill and needs some assistance, towards helping those to whom there aren't the same sort of bonds but where you're making a bigger - the maximum - difference. If we're really speaking about effective altruism then helping your relatives is not a part of it. It may be something that's a nice thing to do, that shows the kind of person you are, but if you're living in a country like the United Kingdom it's very unlikely, almost impossible, that this could be the most effective thing you could do with your money from an altruistic point of view.

GWWC: You've mentioned GiveWell and Giving What We Can. I wonder if you have a picture of how charity is changing, how the effective altruism movement fits into this, and how new technology and data is changing the way we approach altruism and charity?

Peter Singer: I think it is changing! I think it's changing in part because of the emphasis on effectiveness, which has been around for a while and is increasingly taken seriously. If you go back a decade or so there was not much going on in the way of assessment. There was an American site called Charity Navigator which people would go to if they were looking for the 'good' organizations, but all charity Navigator did was to tell you how much of organizations' revenue went for administration and how much went for programmes. That's really a very naïve way of looking at how effective a charity is. Of course you can reduce your administrative expenses by not employing staff who will find the best programmes to fund. Then even if 95% of your revenues go to programmes these may be no good. Around that time we started getting people looking seriously at evaluation. There was the Poverty Action Lab set up by Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee at MIT which then had a spin off at Yale, Innovations for Poverty Action. Then GiveWell started alongside other organizations in other countries and Giving What We Can.

You're right that the availability of more data has been a part of this change, as has the Internet in bringing people together. If you ask "where are people really discussing effective altruism"? Sure, Esther Duflo and Dean Karlan at Yale are publishing studies in academic journals, and that's significant, but the lively discussions have been going on online, and they're enabling people from what was really quite a small community of interest to start with (and though growing remains small) to find each other. People who thought they "are the only ones to be bothered about this" are starting to see that there are other people with good ideas and similar concerns.

GWWC: We talked about effective altruism and it seems a demanding - or what some people might think of as a demanding - lifestyle. Do you think that without religious commandments or the categorical imperative of other moral systems there is enough impetus there to follow this sort of ethics?

Peter Singer: I think there is enough impetus for people to follow a kind of ethics which points in the direction of altruism. I think one of the interesting things about the effective altruism movement is that it includes a lot of people who are secular as well as a lot of people who are religious, and they agree on the goals. On the basis of the evidence we have so far, I would say, that there are plenty of people who are motivated sufficiently by knowing what difference they can do without needing any kind of religious backing. I think the movement will continue to grow but maybe at some point it will begin to plateau and that may be because there are people who are not sufficiently motivated by the difference they can make. But to some extent that depends on the culture and the people they are surrounded by. We have to wait and see how the movement continues to expand.

GWWC: If we're talking about effectiveness and consequentialism, do you think there is a case for instituting charitable targets in law?

Peter Singer: To some extent, that already happens because the government legally taxes you and gives some of it to foreign aid. I don't favor a law that says everyone must give x percent of their income to charity. I think that if a government wants to do something like this, it can increase the money given to foreign aid. The government can also educate people and make it easier for them to give, as can corporations. I don't want to make it compulsory.

Look out for part two of this interview - in which Peter Singer discusses effective careers - coming soon.

--

This is a slightly compressed and edited version of the original interview.

Thanks to Sophie Hermanns, Luke Ilott, and others for leading the interview and Markus Anderljung for transcribing the interview!