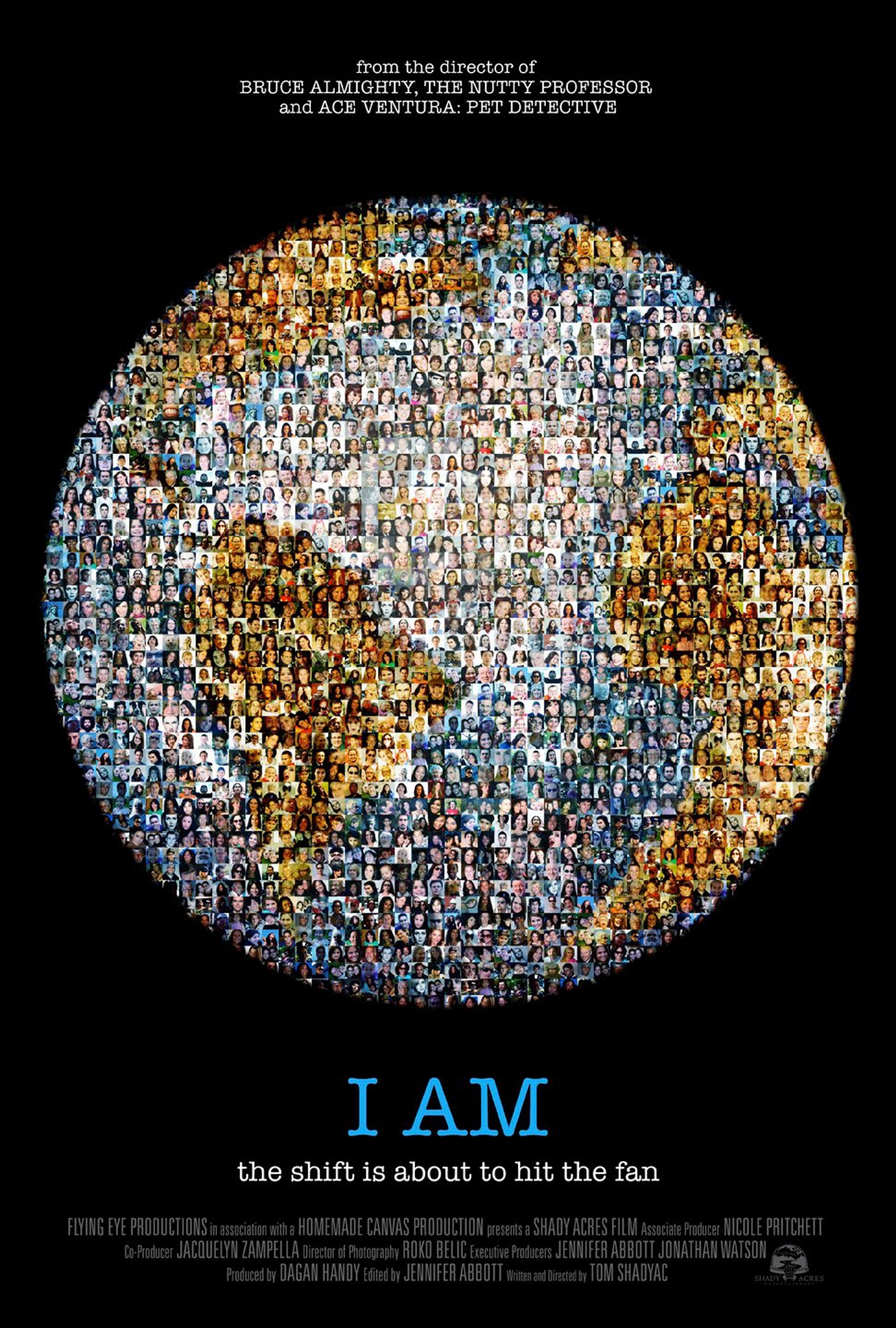

On 24th January 2013 I was invited to take part in a discussion panel at the European premiere of the movie documentary “I AM”, directed by and starring Tom Shadyac.(1) This blog post is intended mainly as a summary of what I thought of the film, but will also describe how I felt being part of its launch.

The film is an account of Tom’s journey around the world, speaking to the ‘significant minds’ of today. He asks them two questions ‘what’s wrong with our world?’ and ‘what can we do about it?’. He receives a wealth of answers, some of which I’ll go over, but the main conclusion was in the spirit of G.K. Chesterton’s response to The Times’ request to write an essay on the topic of “What’s wrong with the world?”: “Dear Sirs, I am. Sincerely yours”.

This is one of my favourite aspects of the film. Tom Shadyac gets to play the flawed protagonist in his own piece. He himself became very wealthy in a short space of time after his first films were a success, so naturally, he ‘went shopping’. This included buying two progressively large mansions, and a whole host of exotic nik naks. After reaching this point he realised that he was not actually much if at all happier than before he was successful, priding family and community values above those of financial and social success.

He decided that a change was needed for the morally better, and gave up a large portion of his wealth, using it to start up a homeless shelter in Virginia, and donating a significant amount to Telluride. He gave up his 17,000-square-foot Mansion in Los Angeles, greatly simplified his life and moved into a trailer park.(2) After a near fatal mountain biking accident in 2007, Tom suffered post concussive stress disorder, and, having almost been killed, claims not wanting to die without having shared his story. This is the purpose of “I AM”.

It covers some topics that resonate strongly with the idea that giving can be a part of someone’s life, and one’s own personal wealth is much less important than we think, once our basic needs are met. It explains the sociological factors behind the attitude that has developed within (certainly British and American) culture that to succeed in life is to succeed on a material and financial level, and that the idea underlying a big part of this attitude is that ‘greed is good’.(3)

We are conditioned to take more than we need and do it en mass as a society, so that it doesn’t even strike us as greedy or decadent, but just normal. What struck a chord for me was the presentation of this attitude in a single line close to the end of the film: “There is a word for something that takes more than it needs. We call it cancer”. I can’t fault the presentation of the problem. Associating greed with disease is something that will likely add a lot of strength to people’s perceptions that an overabundance of material wealth is a morally questionable idea.(4)

This takes us through (more or less) half of the film. The next half, while putting across a message that I think we should all take on board – that helping other people, no matter who and where they are, is a good thing – left me a little more perplexed than inspired.

The idea he gets at is that people are brought up to be self-centred and function as individuals, but are actually more interconnected as a species than we might have believed. Many examples are used to illustrate this. One of the wilder ones was the notion of quantum entanglement being casually introduced, to illustrate the fact that physical distance can make no difference to the close relationship between two such objects as electrons.

One of the most memorable points has Tom Shadyac sat in front of a petri dish of yoghurt with active cultures, with a voltmeter connected to it, registering activity with changes in his emotions (i.e. when he considered calling either his agent, or lawyer). The message to take from this? Nature is such that we are all connected to things as random as yoghurt, in ways that we don’t quite understand. So by extension, humans are connected to each other as a global species, on an emotional and physical level.

There’s a lot to take in here, and I’m fairly sceptical about how much you need it all to want to help other people. The yoghurt experiment was funny to watch, and would make a great attraction at a science fair, but I don’t really need to be told that I or anyone else is on any level connected to yoghurt to think that using my time and money to try to improve the lives of other people is generally a good idea.

The main concern I have though is that despite all this information, and despite the fact that one of the key questions being asked is ‘what can we do about the world’s problems?’ there is very little in the way of calls to action. In fact there are none. The viewer is left with a feeling of wanting to help, but information on how to, and the best way of doing this, is seriously lacking.

This was reflected in the discussion. When Tom was asked what he thinks we should actually do, he replied that he couldn’t tell a person how they could do good, but that we should all engage with the message that he tries to convey: we are conditioned to want a lot of stuff, but ultimately connected to everyone and everything else (even yoghurt). I don’t think this is enough though. It doesn’t leave anyone with any answers, just more questions. What are the worst problems? Who can solve them? What can I do to help?

For someone who sees this and is left with these questions, the best thing that could happen is that they stumble across the Giving What We Can website. We will tell you just how you can do this.

(1) Tom Shadyac is the director of Ace Ventura, The Nutty Professor, and Bruce Almighty. As you can imagine, he is pretty cool.

(2) Despite the humble sounding name, this is in fact the exclusive Paradise Cove in Malibu. I think if I ever ended up living anywhere remotely like this place, I would consider myself to have fallen on my feet.

(3) This speech by Gordon Gekko is referred to in the film.

(4) There is evidence that our sense of disgust is causally related to our feelings of moral condemnation.