Endgame for Polio?

Polio cases have decreased by more than 99% over the past 25 years, in part due to the efforts of the Gates Foundation, which galvanized the global community to end polio. Further, the success of India in becoming polio-free provides the last three countries, where polio is still endemic, with optimism. However, political and security reasons have raised difficulties in ensuring that polio eradication will be accomplished by 2018.

Polio is an infectious disease transmitted through contaminated water and food. It attacks the nervous system, leading to paralysis, which may result in permanent disability, and it can be lethal. The lack of a cure and the lack of symptoms of the disease in most cases of infection have made polio eradication an incredibly difficult endeavour.

Background to the fight against polio

The first major step towards tackling the disease was made in 1988 when the World Health Assembly launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) with the aim of eradication of polio by 2000 . At the time, wild poliovirus was endemic in 125 countries and about 350,000 people were paralyzed by polio every year.

The efforts of the global community have been immensely successful, resulting in the Americas being polio-free by 1994, followed by the Western Pacific Region (including China) in 2000, and Europe in 2002. The launch of comprehensive vaccinations programmes played a decisive role in this extraordinary progress.

Since the launch of the GPEI, the incidence of polio has decreased by more than 99%, while the number of countries which remain polio-endemic has been reduced to 3 (Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan).

In 2012, the world recorded the lowest number of reported cases of polio in its history, while India became another polio-free country. Such promising news gave hope that the world’s struggle to eradicate polio might be over in the very near future. However, the final stages of the initiative have been more challenging that it initially seemed, resulting in the announcement of a new six-year strategy: The Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013-2018.

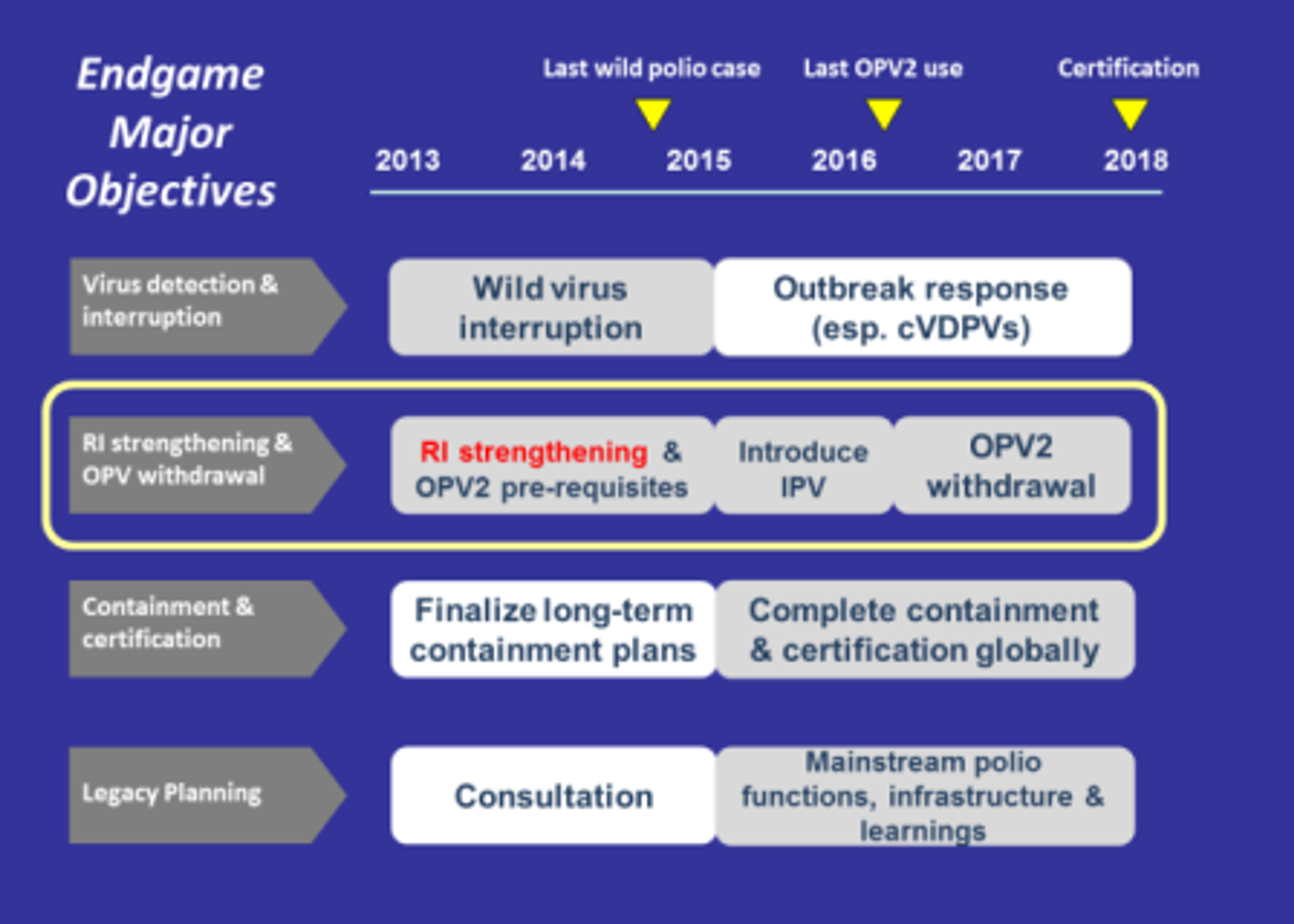

The four main goals of the plan are to:

- Detect and interrupt all polio transmission

- Strengthen immunization systems

- Contain polio and certify the interruption of transmission

- Plan steps following the end of polio

India: a reason for optimism

The example of India gives strong evidence that international efforts (led by the WHO, the Gates Foundation, the Rotary Club and UNICEF) will start to pay off in the near future. India faced many challenges which made the implementation of a comprehensive immunization scheme particularly problematic. These included:

- High population density and birthrate

- Poor sanitation

- Inaccessible terrain

- Reluctance of sections of society, in particular parts of the Muslim community, to accept the polio vaccine.

In 2009, there were 741 reported cases of polio in India, more than in any other country in the world, according to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. This led experts to predict that India would be the last country to stop polio.

‘Micro-planning’ played a major role in bringing India closer towards the goal by making the approach to immunization more systematic. Collecting data about particular places - including areas to be covered by each vaccination team on each day, names of the vaccinators, and of the community workers assigned to the area along with the vaccine - was at the heart of the country’s success.

UNICEF increased the effectiveness of the campaign by setting up the Social Mobilisation Network for Polio in 2001 in the northern Uttar Pradesh state, one of the areas with highest incidence. The workers focused on increasing routine immunization coverage, and promoting habits that reduce the chance of infection (for example, exclusive breastfeeding up to six months, better hygiene and sanitation, and diarrhoea management with Zinc and ORS).

The introduction in 2010 of the bivalent oral polio vaccine (bOPV), which protects against both type 1 and type 3 polio, contributed significantly to the good results. However, it was the communications strategy that lay at the heart of India’s victory. Traditionally, a reluctance to vaccinate a child when sick was one of the key reasons for children to miss vaccinations. A 2011 KAP Study showed a rise in the percentage of caregivers willing to vaccinate their child when sick – from 66.6% to 83.3% in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and from 76% to 90% in Bihar, while the percentage of respondents from the high-risk areas (HRAs) of UP who said they had heard negative rumours about polio drops fell from 29.5% in 2010 to 19.1% in 2011.

Eradication and Endgame for Polio

The Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013-2018 sets out the strategy to deliver a polio-free world by 2018. The Gates Foundation played a leading role in bringing the global community into action, by pledging US$1.8 billion to this cause at the Global Vaccine Summit in 2013. A group of countries promised another US$ 2.2 billion towards the Strategic Plan’s US$ 5.5 billion six-year budget.

The difficulty of conducting effective vaccination programmes in conflict-ridden areas might turn out to be a difficult obstacle to overcome. In Nigeria, nearly half of the polio cases were located in Borno and Yobe states. Those areas, controlled by Boko Haram, a jihadist organisation, have been difficult to access. For example, during a polio vaccination campaign in May 2013, more than 295,000 children (18% of the under- five population) could not be immunized in Borno. Meanwhile, violent incidents that have taken place since Boko Haram gained control, including the death of nine female vaccinators in north Nigeria, has made it harder to recruit vaccinators.

A similar situation is taking place in Pakistan, where it is estimated that 56 people, including vaccinators and police providing security, have been killed in attacks conducted by tribal rebels since December 2012. A recently launched attempt to vaccinate more than 700,000 children fell short of the target by nearly 300,000 children due to inability to deliver the medicaments to unsafe areas of the country. The correlation between insecurity and the recorded number of polio incidences clearly indicates the violence is a major threat that may derail the plan to eradicate the polio by 2018. In 2014, the number of reported cases of polio in Pakistan has already escalated to 160 – the highest number among the last three endemic countries.

Furthermore, the disease has spread to countries which had been polio-free in recent years. The on-going conflict in Syria (which was, according to the WHO, free of polio in 2009) has made it one of the countries most threatened by the spread of the disease. It is estimated that vaccination rates in Syria fell from 91% of children before the war to an estimated 68% in 2012. The number is expected to be much lower for rebel-controlled areas, where most of the cases have been reported so far. The efforts to contain the spread of the disease should be at the top of the priority list of the states’ authorities.

To ensure that the recent resurgence of polio will not be a major setback for the campaign, the WHO has declared a public health emergency and urged the countries which are most likely to export the virus to immunize adults travelling abroad. The results are yet to be seen. However, given the lax border control in many areas where polio has re-emerged, the most straightforward solution is the mobilization to eradicate the virus from the last 3 endemic countries, thus preventing the spread of it to other countries, and finally putting an end to the long battle with polio.

Even if the global community does not succeed in eradicating polio by 2018, the campaign has had an enormous social and economic impact. On top of saving 10 million children from paralysis, the polio eradication campaign has aided the fight against other preventable diseases. For example, National Immunization Days were used as a platform to distribute vitamin A supplements. Meanwhile, the economic benefits of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, presented in the study ‘Economic Analysis of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative’, were estimated at US$40-50 billion, while the provision of vitamin A can have an impact of as much as US$ 90 billion. The latter campaign would not have been nearly as effective if it had not been conducted with the comprehensive polio vaccination schemes. There is potential to replicate the logistical and administrative aspects of the campaign to tackle other preventable diseases.