An AIDS-free generation? A summary of the discussion held on the Guardian Development Blog

Hillary Clinton, US secretary of state, released a five-point plan in 2012 designed to eradicate AIDS. As soon as more victims are treated than infected every year, an AIDS-free generation should be in sight, given advancements in technology which prevents the spread of AIDS from mother to infant.

How far away are we from the AIDS-free generation? Can we overcome a presently incurable disease with new technology? What are the political problems on the road to the AIDS-free generation? Dozens of articles on the three broad themes of funding, technology and policy have been written on the Guardian development blog over the last three years. This blog post summarises their content.

Funding

Before going into the material from the Guardian, please note that you can find a list of relatively effective HIV/AIDS interventions and the problems they are tackling at the bottom of this post.

The big event shaking the development community over the last three years was the decision of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to cancel its funding round in 2012. Essentially, the two big factors behind it seemed to be lack of funding from European countries shaken by the Euro-crisis, and a decreasing interest in the cause. There seemed to be a widespread rationale amongst policy makers of “so much funding has gone into HIV/AIDS over the last 10 years, aren’t we pouring disproportionate amounts of money into this cause?”.

The Global Fund has had a huge impact over the last ten years. Take Malawi as an example. In 2012 it had managed to put 76% of all those who need it on treatment, most often antiretrovirals. Malawi got more than 90% of its funding to combat AIDS from the Global Fund. The health system of Malawi really hinged on resources from the Global Fund. Around the globe, the fund supported programs in over 140 countries in 2014. These programs had 6.6 million people on antiretroviral therapy for AIDS, have tested and treated 11.9 million people for TB, and have distributed 410 million insecticide-treated nets to protect families against malaria.[1]

So the Global Fund's decision to cancel its funding round in 2012 had huge significance for countries like Malawi. People living with HIV are dependent on antiretroviral treatment to stop the infection from developing, and to hinder the development of AIDS. Furthermore, someone infected by HIV is 96% less likely to transmit HIV to his/her partner if on a standard combination of antiretroviral drugs.[2] Discontinuing treatment would therefore not only fail our responsibility to those on treatment, but it would also put the AIDS-free generation at risk by increasing the spread of HIV.

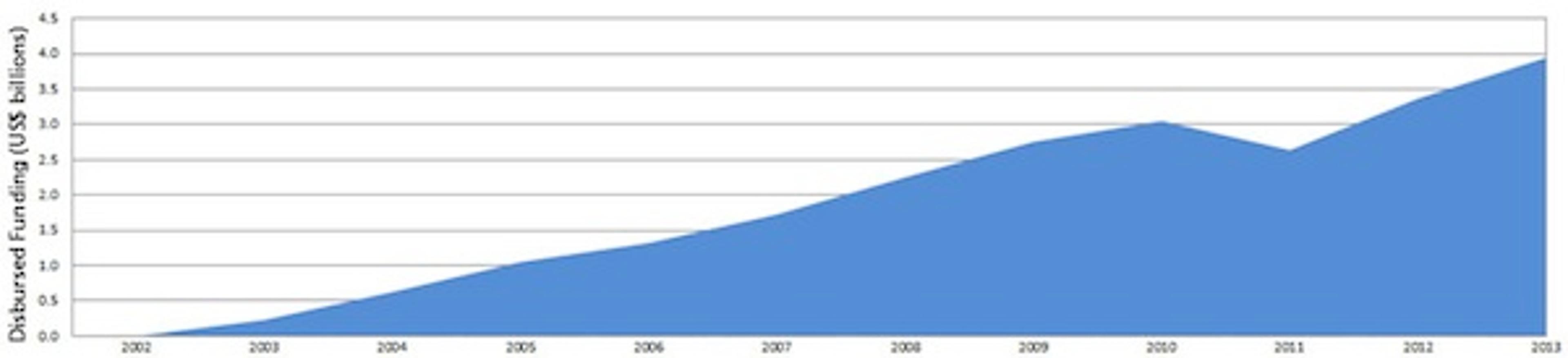

Fortunately, the Global Fund is back on track, as shown in the figure below. A good point to take from this would probably be that other causes remain underfunded, or at least less well funded than the fight against AIDS. This suggests that individual donors can have more impact within other causes, such as intestinal worms and Malaria. Find out more about some of the most effective charities here.

Figure 1: The Global Fund Annual Disbursements 2002 - 2013 [3]

Technology

Are we moving towards a cure for AIDS? Sadly, no. The only person ever to have been cured of HIV had a bone marrow transplant from another person who was resistant to HIV. This is a prohibitively expensive procedure. However, we have many reasons to celebrate a few advances that occurred over the last few years.

The WHO started recommending giving antiretroviral drugs to everyone with HIV since this has been shown to limit the spread of the disease to uninfected people. In fact, the WHO reported that increased access to HIV services, such as antiretrovirals, resulted in a 15% reduction in new infections over the past decade, and a 22% decline in AIDS-related deaths over the last 5 years.

Both UNAIDS and Medecins Sans Frontieres were very positive about the recommendation. This advancement opens up new possibilities for effective interventions in combatting the spread of HIV. This advance might even open up opportunities for individual donors to have significant impact. If we could finally get the rate of HIV infection to reach zero, then the AIDS-free generation becomes a very tangible goal.

An interesting application of antiretrovirals as preventive treatment is a vaginal ring which works by disseminating the antiretroviral drug into the tissues of the vagina. A major trial of this was launched in Africa in 2012. One advantage of the ring is that it’s safe to use a higher dose of the drug than could be taken orally, without the toxic effects. It should also be possible to combine the ring with hormonal contraception. Some studies have suggested that hormonal contraception increases the risk of HIV infection.

New technological advances have also been made in tests for the stage of HIV. A new machine called “the Samba machine” has lowered the cost of one viral load test from >£25 to £10 per test.

The Samba machine is also much quicker. Instead of having to wait for over three months, a person in rural parts of Malawi can now have the test results in an hour.In terms of follow-up, this means a lot. Hospitals have previously reported that people never show up for their test results, and thus that treatment was never distributed. Additionally, the disease may well have progressed over three months, leading to the hospital distributing the wrong kind of antiretroviral drugs.

The Samba machine therefore promises more effective interventions in the future. WHO says viral load testing, which detects the level of HIV virus in the blood, is the best way to monitor the effects of antiretroviral treatment.[4]

Politics

A few significant political developments have shaken the development community over the last few years. The most significant one, perhaps, was the reversal of the US anti-prostitution pledge in 2013.

The anti-prostitution pledge requires NGOs that receive US federal anti-HIV/AIDS or anti-trafficking funds to adopt organisation-wide policies opposing prostitution. The Obama administration had previously been divided on the issue, with the President declaring that a reversal was necessary in 2010, but later reverting on this statement. The pledge was finally abolished in 2013 by the Supreme Court on First Amendment grounds.

The reversal means that funds can now reach sex workers and other people in very vulnerable situations, and should thus be seen as a humanitarian victory. You can find a very good article on empowerment and community for sex workers in India here.

A negatice development is the continued distrust of western health workers and doctors in developing countries. We find an particularly relevant example of the risk of mixing foreign policy and healthcare in Pakistan. CIA operatives disguised themselves as polio vaccinators to gain greater access to Osama bin Laden’s compound in 2011. While the mission achieved its goal, it later led to reversals in local efforts to eradicate polio.

Special attention to this problem has also resulted from the outbreak of Ebola. There seems to be a good cause to ignite a debate of whether to keep public health services, security services and foreign policy separate.

Big Pharma and other commercial giants have also been the stuff of headlines in the context of the struggle against AIDS. Coca-cola started a big collaboration with the Clinton Foundation and the government of Mozambique to speed up distribution and improve storage of medicines and tests. Some people in the development community met this collaboration with scepticism.

Additionally, GloxoSmithKlein (GSK) partnered up with Save the Children to speed up delivery of antibiotics and other medicines to children. Some philanthropists remain uneasy about the collaboration given GSK’s past actions and Medecins Sans Frontieres have stressed that GSK still needs to make antiretrovirals and other medicines truly cheap in poor countries. Nevertheless, this project in particular should be a step forward in the fight against under-5 mortality.

List of a few interventions

Antiretroviral treatment

The control of HIV/AIDS usually includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs, aimed to control the HIV infection. There are different stages of the HIV-cycle, and different drugs need to be used at different stages. Antiretroviral treatment maintains the functioning of the immune system, decreases the patient’s total burden of HIV and prevents the opportunistic infections that often lead to death. It is estimated that antiretroviral therapy saved 700,000 lives in 2010 alone [5].

Male circumcision

According to some scientific studies, though importantly not all, male circumcision can reduce female to male transmission of HIV by 60%. Male circumcision is seen as a cheap way to fight AIDS in Zambia. Given its low cost and purported effectiveness, donors have started pushing it as a prevention strategy. However, some fear that it could discourage condom use.

Condom use

Condom use has been pushed as a very effective measure to prevent the spread of HIV. It’s cheap and it’s effective. However, the success of mass campaigns for the use of condoms varies and such campaigns are largely out of fashion. The very effective “Take control” campaign in Namibia was discontinued in 2011. Interventions to increase condom use may still be very cost-effective.