Action on Smoking and Health

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we’re relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Cause Area: Dementia (Alzheimer's Disease)

Donor fit:

dementia prevention; cancer prevention; public health in the UK;

What do they do?

ASH is an advocacy group originally established by the Royal College of Physicians and currently overseen by an advisory board of 70 academics and professionals from the fields of medicine, public health, public relations and politics.1 They are active in two separate areas: providing information and networking, particularly aiming to develop awareness of the health impacts of tobacco and develop public opinion; and advocacy and campaigning, through which they attempt to bring about policy changes which reduce the disease burden due to tobacco.

One example of their recent work is the 2015 publication of Smoking Still Kills, a report outlining a policy strategy to minimise smoking mortality in the UK by reducing smoking among adults to 13% by 2020 and 9% by 2025 (with the eventual goal of 5% by 2035),2 which was timed to coincide with the end of the UK government’s Tobacco Control Plan.3 Their other recent work includes: campaigning for standardised packaging (passed in March of 2015, and recognised by the Shadow Public Health Minister as largely the result of ASH’s work);45 campaigning for the prohibition of smoking in cars when children are present (passed in February of 2015);67 campaigning for the introduction of an additional tobacco levy, a Minimum Consumption Tax, and an updated anti-smuggling strategy.8 They have also been active in organising protests outside general meetings of major tobacco companies,9 and consistently successful in securing media coverage and discussing key issues related to the health impacts of tobacco use.10 They also act as the secretariat for the All Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health, and thereby coordinate a large portion of parliamentary efforts to combat smoking.1112

Overall evaluation

We are quite confident that, of the charities operating in the UK, ASH is not only one of the most cost-effective in reducing the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, but also improve health more generally. Although it works through indirect means, through tobacco control and also through lobbying, and although its cost-effectiveness does not exceed that of our top recommended charities, we do believe that the expected impact of ASH’s activities on Alzheimer’s morbidity and mortality in particular and other diseases more generally, are quite considerable. This is due to the consistently high quality of its implementation, how well-placed it is to effectively lobby and advocate for tobacco control, its past successes (which were both sizeable and also achieved on quite a low budget), its strategic approach to future activities, and the projected cost-effectiveness of those future activities.

We estimate, with a great deal of uncertainty, that ASH is able to advocate through the news media at an average cost of 281 views through traditional media and 1,079 online views for every £1 spent throughout the year. We also estimate that some of ASH’s past activities have reduced annual deaths due to Alzheimer’s disease at a cost of £283,000-£525,000 per death per year (£14,000-£26,000 per death prevented over 20 years, undiscounted), and that ASH’s activities over the next 5 years may continue to do so at a cost of £531,800-£985,000 per death per year (£26,600-£49,200 per death over 20 years, undiscounted). Of course, this is far lower if lung cancer, stroke and other health conditions caused by smoking are also included. For Alzheimer’s disease specifically, these figures indicate that ASH’s cost-effectiveness is not as high as for the top charities working in developing countries, but it still appears to be one of the best opportunities for reducing the disease burden, of Alzheimer’s and more generally, in the UK.

Quality of implementation

For lobbying and advocacy, it is much harder to rigorously evaluate a charity’s effectiveness and, therefore, the quality of their implementation and the effect of their activities to date are extremely important. In particular, the methods they use and their past impacts are the best indicators we have of whether they might continue to be effective. However, on the basis of both indicators, ASH appears to potentially be able to continue to reduce smoking rates very effectively.

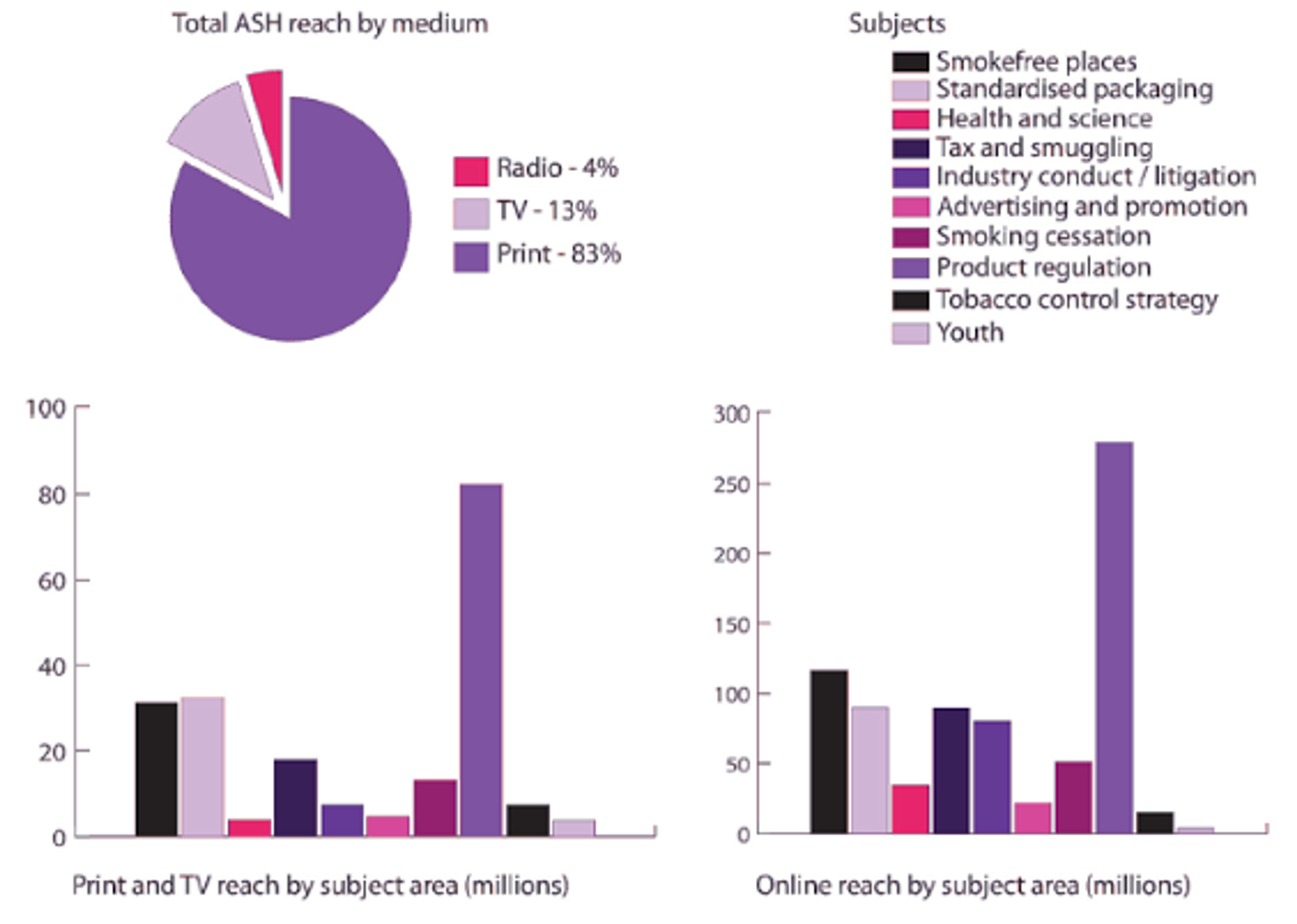

There is also evidence that ASH’s work is effective, in that they have consistently had a great deal of success in the past and rate highly on various metrics. For instance, in 2015 they made 44 press releases and received 3000 mentions in the printed press, 249 mentions on radio and 76 on television news.13 The majority of this consists of advocacy in favour of anti-smoking measures, criticism of tobacco companies, and discussion of the health impacts of smoking.1415161718192021222324252627 This has resulted in a weekly reach, ASH claims, of 3.9 million through traditional media and 15 million online. This greatly exceeds any other known anti-smoking organisations in the UK and the claim that ASH is currently the leading public voice in anti-smoking advocacy appears to be quite accurate. It also indicates that ASH is quite well-respected by news agencies - likely due in part to the involvement of eminent medical professionals and academics - and well-placed to continue to have an impact in this way, although the eventual impact of these media appearances on health cannot be determined. From a cost-effectiveness standpoint it is also very impressive, as ASH’s expenditure for 2015 was only £722,901,28 and this averages to 281 views through traditional media and 1,079 online views for every £1 spent throughout the year. This is not separating the costs or including the effects of any of their other activities, particularly lobbying, so this is a very low estimate of their actual reach per £1 spent on public advocacy.

Figure 6: Reach of ASH’s media coverage between September 2014 and August 2015, by medium and subject area.29

ASH’s policy and lobbying work also appears to have been effective. Several of the policies recommended in their 2008 report Beyond Smoking Kills,30 and later advocated for by ASH, were later incorporated into the government’s Tobacco Control Plan and later legislated for - including standardised packaging, the prohibition of tobacco sales from vending machines, prohibition of point of sale displays of products, prohibition of smoking in cars with children, and aiming for an 11% smoking rate by 2015.31 Apart from the 11% smoking rate, all of these were achieved (the current rate is 18.3%).32 This alone is not sufficient to establish ASH as the primary cause of these changes, but there has also been explicit recognition of ASH’s role in bringing these about, such as: the Shadow Public Health Minister’s public acknowledgement of ASH’s role in getting standardised packing passed;33 the direct involvement of ASH with the All Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health;34 and the prominence of ASH in the media coverage surrounding these breakthroughs.35363738394041 It was also recognised that the 2006 ban on smoking in all indoor public spaces was the direct result of ASH’s campaigning,4243 a change which was expected to lead to 600,000 people quitting smoking (at an estimated cost of £50 million).4445

ASH’s current efforts also appears to be well-directed, with their recent publication of Smoking Still Kills at a time when the government’s Tobacco Control Strategy is set to expire,46 and their continuing pursuit of well-evidenced policies which are expected to be highly effective, such as: specific smoking reduction targets, for specific socioeconomic groups; greater funding of mass media campaigns; a direct levy on tobacco companies to fund other tobacco control initiatives; the requirement that tobacco companies make their sales data, marketing strategies and lobbying activities public; increased funding for the NHS’s Stop Smoking Services; mandatory instruction on smoking cessation in medical training; regulation of the market of nicotine products which do not contain tobacco, in order to maximise their availability to smokers and minimise the chance of uptake by non-smokers;47 further increasing the excise tax on tobacco products, including an increase in the tax escalator to at least 5% above the rate of inflation; removing the tax differential between manufactured and hand-rolled cigarettes; a positive licensing scheme for all tobacco retailers; consultation about the prohibition of smoking in select outdoor areas; and warnings and possible reclassification for films and television shows containing tobacco use.48

The most prominent example of their recent work is the 2015 publication of Smoking Still Kills as mentioned above, a report outlining a policy strategy to minimise smoking mortality in the UK by reducing smoking among adults to 13% by 2020 and 9% by 2025 (with the eventual goal of 5% by 2035),49 which was timed to coincide with the end of the UK government’s Tobacco Control Plan.50 Their other recent work includes: campaigning for standardised packaging (passed in March of 2015, and recognised by the Shadow Public Health Minister as largely the result of ASH’s work);5152 campaigning for the prohibition of smoking in cars when children are present (passed in February of 2015);5354 campaigning for the introduction of an additional tobacco levy, a Minimum Consumption Tax, and an updated anti-smuggling strategy.55 They have also been active in organising protests outside general meetings of major tobacco companies,56 and consistently successful in securing media coverage and discussing key issues related to the health impacts of tobacco use.57

Cost-effectiveness and robustness of evidence

The best evidence available for a political advocacy organisation is its past successes, and ASH’s past work suggests that it is indeed quite cost-effective in reducing smoking prevalence. Likewise, its future plans are also very promising and indicate that it is likely to continue to be cost-effective.

As one case study of its past activities, in 2003, ASH began to campaign for a ban on smoking in enclosed public spaces throughout the UK,58 which was eventually enacted in 2006 and has remained in place until present.59 The passing of this legislation was attributed largely to ASH’s involvement,6061 and led to an estimated 600,000 people quitting smoking.6263 According to our estimates in Section 4.2, this equates to 2,966-5,492 cases of Alzheimer’s disease prevented each year, 171-316 deaths, and 1,936-3,584 DALYs due specifically to Alzheimer’s each year.[^fn-166] During that same time (2003-2006 inclusive), ASH’s total expenditure was approximately £2.35 million.64 It was also estimated that the total cost of implementing the policy was approximately £50 million.6566 It is extremely difficult to establish whether ASH’s activities were causally necessary for the policy’s intervention but, due to their leading role, we might attribute 10% of the health benefits to their activities. We might also revise down the 600,000 estimate as potentially exaggerated, to perhaps 300,000. That gives us 50,000 people quitting at a cost of £7.35 million (including both ASH’s costs and the total cost to the public). That is, a cost of £16,000-£29,746 per case of Alzheimer’s prevented, £283,000-£525,000 per Alzheimer’s death prevented, and £25,000-£46,000 per DALY due to Alzheimer’s prevented in a single year. When considered over 20 years, without discounting, this falls to £14,000-£26,000 per Alzheimer’s death and £1,200-£2,300 per DALY due to Alzheimer’s averted (significantly less when the other health impacts of smoking are considered), which is considered highly cost-effective by the NHS, which takes a cutoff of about £25,000 per QALY gained (one QALY gained is very roughly equivalent to one DALY averted) and is even comparable to the cost per life saved through some health initiatives in the developing world. Including all of the health benefits other than for dementia, we can roughly estimate that a life was saved per year for every £13,300 spent, and a DALY averted for every £790, which is even more impressive (again, over 20 years this would drop considerably). Thus, in this instance, ASH’s activities were quite cost-effective in reducing the disease burden of dementia and improving health more gnerally. It is also worth noting that, even if ASH were to have such a large impact only once every 15 years, their low annual expenditure of £500,000-£750,000 suggests that this would not greatly increase the cost per life saved or per case of Alzheimer’s prevented.

As for ASH’s future policy ambitions, we are quite confident that the policies advocated by ASH in Smoking Still Kills will have a net-positive effect on health. In particular, an increase in the tax escalator and removal of differentials for tobacco products will likely result in sizeable reductions in dementia prevalence with minimal expenditure of public funds (see Section 4.2). Improved smoking cessation services and increased funding for mass media smoking prevention campaigns are likely to be, overall, highly cost-effective. In regards to ASH’s expenditure in pursuing these policies and its projected goal of reducing smoking rates to 13% by 2020, we can very roughly estimate its cost-effectiveness in regards to reducing Alzheimer’s prevalence - very pessimistically, we might expect smoking rates to decrease by only half this much (to 15.65%), that ASH may be responsible for only 1% of this reduction, and that ASH’s annual budget over this time (2015-2020) is roughly £800,000. This would still equate to 17,100 people quitting smoking at a cost of £4.8 million, and a reduction in Alzheimer’s at a cost of £30,600-£56,700 per case prevented, £46,900-£86900 per DALY, and £531,800-£985,000 per death.[^fn-166] Again, considered over 20 years (without discounting, this drops enormously, to £1,500-£2,800 per case, £2,300-£4,300 per DALY and £26,600-£49,200 per death prevented. Of course, this is only an extremely rough estimate, obtained through pessimistic assumptions, but it indicates that ASH is likely to continue to be quite cost-effective compared to other domestic health interventions for Alzheimer’s disease.

If we consider the wider health impacts of tobacco use, this cost may again drop considerably. From the number of annual deaths (108,600) and DALYs (1.83 million) attributable to smoking in the UK each year, we can very roughly estimate that ASH’s future work will reduce the overall burden of disease at a rate of £30,600 per 1 death prevented every year and £1,800 per 1 DALY averted every year. Again, over 20 years this would be only £1,500 per life saved and £90 per DALY averted (although this is without discounting and subject to an enormous degree of uncertainty). By the standards of a developed country, this is highly cost-effective - roughly 250 times less expensive than the threshold of the NHS. Thus, for general health, it is likely that ASH is more cost-effective than the vast majority of other domestic health interventions.

However, it is essential to note that, due to the nature of political advocacy, past evidence of success does not guarantee that ASH will continue to be successful. Although we consider it very likely that ASH will continue to produce policy changes with considerable health benefits, it is also very possible that this does not occur. It is hence with an enormous amount of uncertainty that we make this claim, and our somewhat low rating of ‘Robustness of evidence’ reflects this.

Room for more funding

Our communications with the charity have suggested that ASH does have sufficient room for more funding, and that it is highly likely that ASH can continue to use additional funds effectively.

In particular, it appears that ASH is in particular need of donations at present. Recent policy changes at the Department of Health require that grants made to charities such as ASH (which was previously funded largely by government) not be used for any form of political lobbying.67 Given that a large portion of ASH’s activities involve political lobbying, and that £200,000 of ASH’s funding in 2015 came from the Department of Health, this may lead to ASH experiencing a large funding gap in future.[^fn-166]: Our model can be found at https://goo.gl/oaVREA