What values do we need to keep in mind about the DALY? Part I

Should we value the life of a 25 year-old more than that of a 65 year-old simply because they have different social roles? Should we discount future health benefits because it is uncertain whether they will arise or not? Should we think differently about the individual burden of a disease when a whole community is affected instead of just one individual?

This post gives a brief history of the health statistic known as the DALY – Disability Adjusted Life Year. The DALY has come to influence many decisions in global health over the last 20 years. I raise a few problems with the statistic,and emphasise its benefits as a statistic that is comparable across causes.

Introduction – what is the DALY?

The DALY is an attempt to merge data on morbidity and mortality into one statistic, and make it comparable across different diseases and causes. It assigns a numerical value between 0 and 1 to health outcomes, where death, the worst possible case, is assigned the value 1. Thus, it allows for simple addition of different health outcomes. This enables agencies such as the WHO to calculate the disease burden of a particular region, accounting for all the different diseases prevalent in that region.

Moreover, the DALY can also be used to guide resource allocation, by allocating resources to the intervention that saves the most DALYs per dollar. So how do we construct the DALY and put a numerical value on health outcomes? Well, at face value it’s a simple formula:

**DALY = YLL (Years of life lost) + YLD (Years of life lost due to disability)**

Suppose a young adult of 25 years is living in a remote area where there is little access to health care. Tragically, this individual has contracted AIDS, and receives no antiretroviral treatment. Nonetheless, the 25-year-old survives for a year, but then dies of an infection.

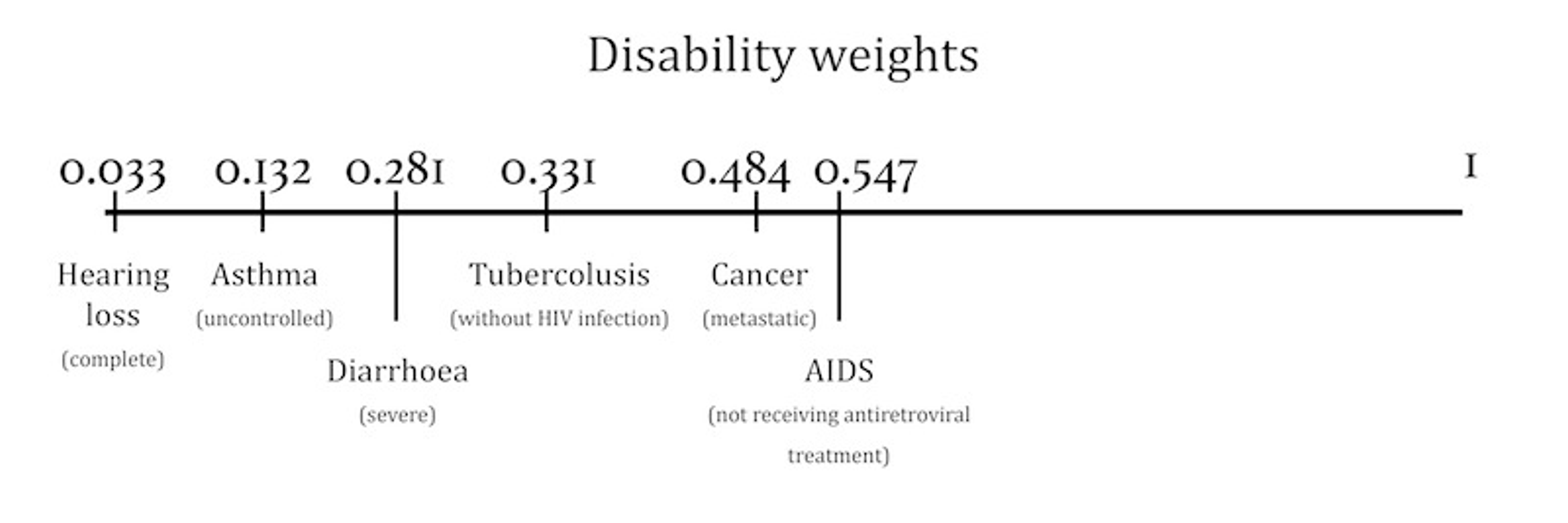

This scenario can be converted into DALYs. First, we need to account for the year lived with AIDS without receiving antiretroviral treatment. The disability weight on this health outcome is 0.547. These weights are numbers between 0 and 1 and they signify how bad a particular health outcome is compared to death. 0 represents a state of full health, whereas 1 represents death. The figure below lists a few common causes and their disability weights. The full list of disability weights is available here.

To get the YLD for the 25-year-old we therefore multiply the number of years lived with AIDS by the disability weights (1 * 0.547 = 0.547). The other component, the YLL, is simply the years of life lost relative to the agreed standard life expectancy (87.8 – 26 = 61.8). The DALYs lost and the total burden of the disease for the 25-year-old is 62.347.

**DALY = YLL (standard life expectancy – age at death) + YLD (years lived with disability * disability weight)**

But wait. Aren’t there at a hundred ethical problems with this method? Well, there are a few. I will describe the four issues I think are most important in this post. Two of these issues have been resolved in the latest update of the Global Burden of Disease study from 2010.

History of the DALY and two (resolved) issues

The original DALY was developed at the Harvard School of Public Health in the late 1980’s. Other measures, such as YLL (Years of Life Lost) and QALY (Quality Adjusted Life Years) were already popular, but they offered no standardised way of measuring morbidity and mortality.

The DALY was subsequently adopted by the Global Burden of Disease 1990 study of the WHO (GBD 1990); a huge project which estimated the total, global disease burden by using DALY methods. The GBD series was later updated in 2004 and most recently in 2010. Over these 25 years, the DALY statistic changed significantly following a lively debate about, chiefly, two ethical issues inherent in the DALY; age-weighting and time discounting.

Age-weighting

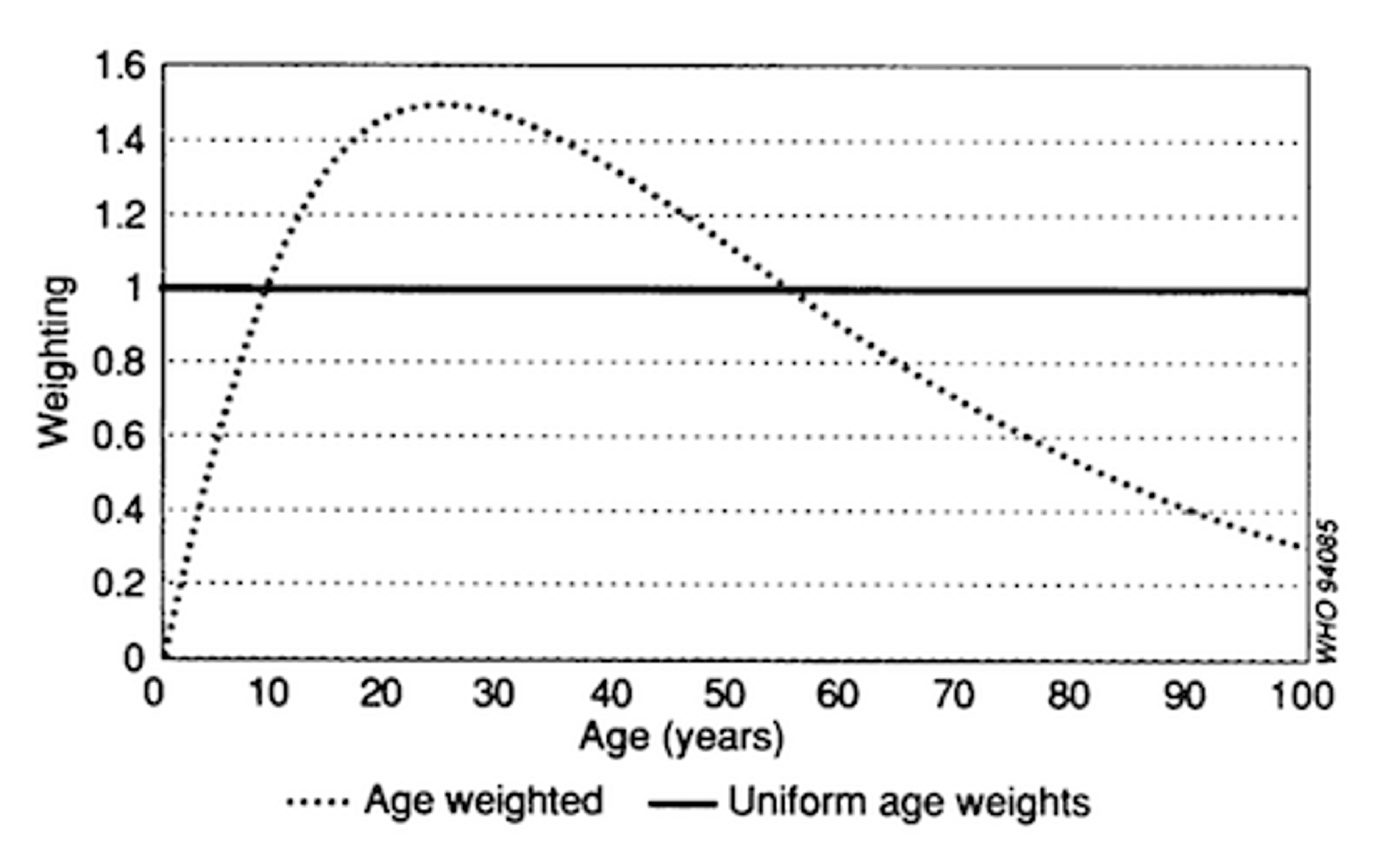

Reasonably, we might ask ourselves – Is it worse if a 25-year-old suffers from AIDS than if a 75-year-old suffers from AIDS? What about infants? Is the death of an infant as bad as the death of a 25-year-old? The original DALY envisaged the weighting of age according to social roles played by people of different ages. C. J. Murray explains the technical basis of the DALY in his 1994 article Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. The weighting of age in the original DALY followed the function in the figure below.

Figure 2

The weighting peaks at around 25 years, and decreases as age increases. Furthermore, the weighting starts at 0 at birth and increases quickly until the age of 25. This implies that the death of an infant, at birth, is weighted as 0 DALYs (nothing). So the death of an infant is definitely not regarded as bad as the death of a 25-year-old. And the weighting of age is linear. This implies that, in terms of DALYs, one 25-year-old suffering from AIDS for one year is approximately as bad as two 75-year-olds suffering from AIDS for one year.

Murray did not justify age-weighting by some differential intrinsic valuation of life. Rather, age-weighting was an attempt to capture different social roles at different ages. The young and the elderly depend on young adults for care, emotional and financial support. Sickness and death among this group of individuals is therefore particularly serious.

But if we open up for the possibility of weighting according to social roles, shouldn’t we also weight individuals across professions and income? What about doctors and nurses? Since people depend on them for care shouldn’t they also be given a higher weight? It turns out this kind of weighting is quite problematic. By weighting people according to their age we open up many other issues that would have to be considered before we could justify the application of age-weights. Furthermore, numerous critics voiced concerns about the universalism of a human life. The practise of age-weighting was consequently abolished in the GBD 2010 study.

Time discounting

A related issue is time discounting, a constantly relevant problem in cost-benefit analysis. Toby Ord and Robert Wiblin have written extensively on this issue in our section on Theory Behind Effective Giving. Discounting is the practise of applying higher weights to benefits that arise in the present relative to the future. For example, most people would prefer getting a piece of chocolate today than tomorrow (see, for example, this experiment on present-bias). And I wouldn’t exchange $100 this year for $100 next year, chiefly because I could take the $100 today and invest them such that my return would give me more than $100 next year. We usually model this phenomenon using geometric discounting.

However, the practise of discounting is not as intuitive when it comes to health benefits. Is it better to cure an individual of tuberculosis today rather than next year? Not really. But could this cured individual contribute to society in such a way that we are able to cure more people of tuberculosis next year? Well, maybe, but Ord and Wiblin suspect that most benefits stay with the individual.

Time discounting was originally used in the DALY statistic for technical reasons. Suppose we let DALY estimates guide our resource allocation. What would be the benefits of investing in a research program that produces a vaccine for HIV? If the time horizon is infinite, then the benefits would be infinite, because we would prevent an infinite number of people from contracting HIV. Consequently, if we don’t discount benefits in the future, all resources should be invested in vaccination programs.

What is the problem with this reasoning? As pointed out by Ord and Wiblin, it is not appropriate to assume that no one would ever think of a vaccine against HIV if it weren’t done by one research program in particular. It is not the appropriate counterfactual. It is better to construct an explicit model that assumes that someone else would think of a vaccine in x years. Furthermore, discounting the DALY creates a lot of intergenerational inequality that is quite arbitrary. Originally, the DALY used a discount rate of 3%. This gives a weight of approximately 0.22 to DALYs that arise in 50 years. Is it fair to consider 5 deaths in 50 years as serious as 1 death today?

The most serious implication of age-weighting and time discounting, as noted by Anand and Hanson (1997) was that no one could get rid of these practises without re-doing the entire analysis. Once a disease burden had been calculated for a particular setting it was more or less impossible to exclude time discounting and age-weighting without going back to the original data. This was a serious obstacle to transparency and transferability of results in the global health debate. I join the crowd of positive supporters of the WHO decision to ignore time discounting and age-weighting in the latest Global Burden of Disease study.

In the next post in this series, I will look at the DALY and its role as a measure of disease burden that is transferable across different conditions and illnesses. I will also discuss the future of the DALY, its limitations as an indicator of resource allocation, and an additional method that could include community effects into the DALY.