Parasitic worm infections are endemic in large parts of the world. Eradication of these worms (deworming) has long been considered a simple and cheap intervention that brings substantial health and education benefits to millions of children worldwide. Many organisations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the World Health Organisation (WHO), and Deworm The World support deworming programs. However in recent years, more data have emerged that cast doubts on the effectiveness of such programmes. Most of these studies have already been discussed by Giving What We Can in 2012, with a focus primarily on the cost-effectiveness of treating worm infections [1]. Here, I will mention the most recent findings, and why we believe that deworming is still a worthwhile cause to support.

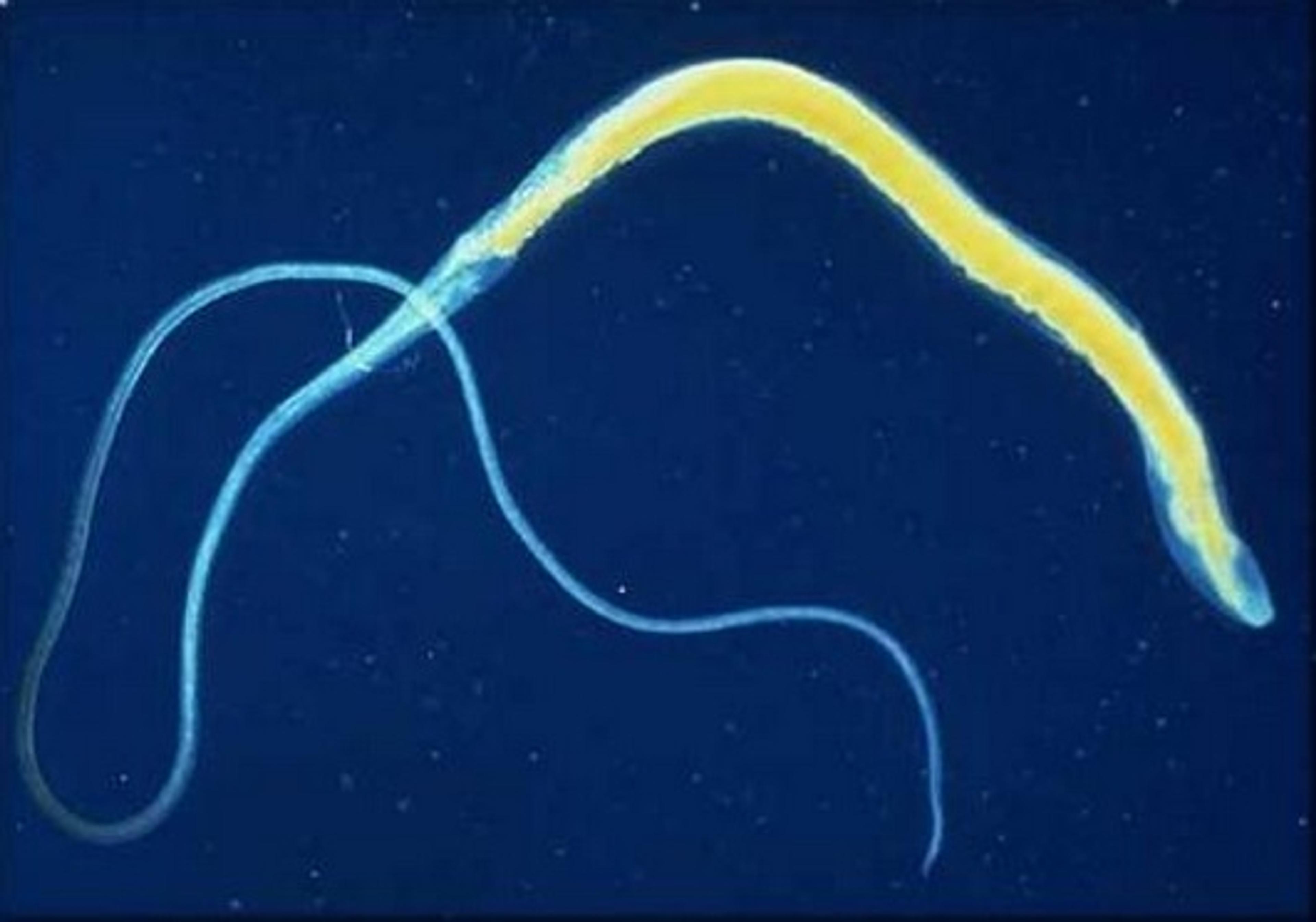

Soil-transmitted worm infections are prevalent in the world’s poorest communities and cause symptoms such as anaemia, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and weakness. The three main types of intestinal worms are roundworms, whipworms (as pictured below) and hookworms, and their eggs pass into the soil through human faeces in regions with poor sanitation. Infection is transmitted when the eggs are ingested via contaminated vegetables or utensils, and hatch in the intestine [2]. According to the WHO, worm infection in children can cause organ damage that exacerbates with age, as well as less direct effects such as reduced productivity, fatigue, and as a result, lower school attendance. It might also worsen other conditions such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS [3].

Although deaths from worm infections are rare, worm treatment has long been regarded a cheap and effective health intervention in the developing world. The earliest example of successful deworming was carried out in the early 20th century in the southern states of the USA. After observing that 40% of children suffered from hookworm infections, John D. Rockefeller’s Sanitary Commission sponsored an eradication campaign, which included treatment with thymol and education about good hygiene. The benefits extended beyond health, with improvements seen in school attendance, enrolment, and literacy [4]. Similar observations were made more recently in Kenya, where mass deworming of schoolchildren led to reduced absence from class [5]. Looking at even more long-term benefits, two unpublished studies reported the results of a Primary School Deworming Program in Kenya, which started in 1998. Besides an improvement in height and weight, children treated for worms worked more hours in adulthood due to improved health and earned 20% more than those not treated [6]. However, the fact that the studies have not yet been published has raised concerns about publication bias [7], while the positive studies were treated with significant reservations by the charity evaluator GiveWell, who argue that the results are not necessarily representative of other regions with a lower worm burden [8].

As always, when there are doubts about the efficacy of a treatment, a meta-analysis of published studies can reveal the true effect. The most recent version of the Cochrane review (2012) assessed 42 randomised controlled trials of deworming. In several studies, children were pre-screened for worm infection before treatment, and showed some increase in weight and haemoglobin levels. However, in the trials where the entire community was treated without pre-screening, there was little or no effect on health parameters, growth, cognitive ability, or school attendance. The exception were two trials showing a large positive increase in weight, however both were conducted over 15 years ago in an area with a high worm burden and may not reflect the situation elsewhere [9].

Overall, the Cochrane review has sparked criticism, notably from Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA). In their blog, IPA argues that the review left out three studies showing a positive effect of deworming (one - the early 20th century study and two unpublished). In addition, if deworming following pre-screening improved certain health parameters, the same effects should be seen in infected individuals during mass deworming projects, even if the data from the whole population do not show statistically-significant benefits. On the other hand, GiveWell, while agreeing that the evidence for the benefits of deworming is low, mentioned that the Cochrane review did not include studies on combination treatment for soil-transmitted worms and schistosomiasis (infections of the urinary tract and intestines by the Schistosoma worm). They maintain that combination treatment leads to improvements in health and development, and, like Giving What We Can, continue to recommend the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) as a highly effective charity [8, 10, 11].

The largest trial to date, conducted in North India, was published in 2013 eight years after it was completed. It studied one million children who were treated with deworming drugs twice a year over a five-year period. A trial this size was an opportunity to test whether treating worm infections would reduce child mortality (in parallel, the authors examined the effects of Vitamin A supplements on mortality). The results were clear and disappointing: long-term deworming had no significant impact on mortality, weight, height, or haemoglobin levels [12]. However, the validity of the methods and results has been controversial. GiveWell raised the question of why a trial this size was not published for eight years since its completion date, suggesting publication bias [10]. Furthermore, a response published in the Lancet journal claimed that coverage of Vitamin A programme was far lower than the 96% reported in the trial, with less than 10% of children reporting to have received a vitamin tablet within the last 6 months of the study. There were also claims of poor monitoring, reporting bias, and little training and incentive given to the Indian workers who administered the drugs [13]. All these issues raise significant doubts as to whether the Vitamin A (and by extension, deworming) study has been properly planned and executed, and the results are not given much weight in the scientific community.

To conclude, although some recent studies have shown no improvements to health and education after deworming, the data are not always reliable and the studies not always well-executed. The mixed results of the studies in the Cochrane review highlight how trial design and monitoring can affect the conclusion, even when the same drugs are used to treat the disease. Furthermore, the current interventions are very cost-effective even considering the recent adjustment of DCP2’s estimate (see the 2012 GWWC post). Overall, it appears that there can be short-term and long-term health benefits to deworming, especially when schistosomiasis is treated together with soil-transmitted worm infections. As a result, both GiveWell and Giving What We Can continue to recommend deworming and schistosomiasis treatment programs such as SCI and Deworm The World Initiative.

References

- Giving What We Can: Neglected Tropical Diseases – Are they Cost-Effective to Treat?

- WHO: Intenstinal worms.

- WHO: Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis, Ref: ISBN 92 4 154710 3.

- Bleakley H. Disease and Development: Evidence from Hookworm Eradication in the American South. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2007;122(1):73-117

- Miguel E and Kremer M. Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities. Econometrica. 2004;72(1):159-217

- Baird et al. 2007 (unpublished); Worms at Work: Long-Run Impacts of Child Health Gains.

- Hawkes N. Deworming Debunked. BMJ. 2013;345, e8558. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8558

- GiveWell: Combination Deworming (Mass Drug Administration Targeting Both Schistosomiasis and Soil-transmitted Helminths).

- Taylor-Robinson DC, Maayan N, Soares-Weiser K et al. Deworming Drugs for Soil-Transmitted Intestinal Worms in Children: Effects on Nutritional Indicators, Haemoglobin and School Performance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000371.pub5

- GiveWell blog: New Cochrane Review of the Effectiveness of Deworming.

- IPA blog: Cochrane’s Incomplete and Misleading Summary of the Evidence of Deworming.

- Awasthi S, Peto R, Read S et al. Population Deworming Every 6 Months with Albendazole in 1 Million Pre-school Children in North India: DEVTA, a Cluster-Randomised Trial. The Lancet. 2013;381:1478-1486

- Sommer A, West Jr K et al. Vitamin A Supplementation in Indian Children. The Lancet. 2013;382(9892):591