Micronutrients

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we're relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

our latest reports on micronutrients are as follows:

Micronutrients are substances needed only in minuscule amounts that enable the body to produce enzymes, hormones and other substances essential for health and growth. The consequences of micronutrient deficiencies can be severe. Iodine, vitamin A and iron are the most important in global public health terms; their lack represents a major threat to the health and development of populations the world over, particularly for children and pregnant women in low-income countries.[1]

Mass fortification involves adding micronutrients to staple foods and appears to be one of the most effective means of combating micronutrient malnutrition. Giving What We Can has reviewed studies documenting nutritional improvements in populations as a result of mass fortification. Reported ‘benefit-cost’ ratios are at 5 or higher, and in some cases over 20. The reported cost of giving one person an extra year of life due to improved health ranges widely, but in many cases falls between $20 -$100. However, the validity of these studies is open to question and there are reasons to be cautious in interpreting the available data. Although our research has mainly focused on food fortification, other promising interventions for combating micronutrient malnutrition also exist and deserve further research.

The illnesses

Iodine deficiency

Iodine deficiency is the world's most prevalent, yet most preventable, cause of brain damage. Serious iodine deficiency during pregnancy can result in stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, and congenital abnormalities such as cretinism, which is a grave, irreversible form of mental retardation affecting people living in iodine-deficient areas of Africa and Asia. However, of far greater significance is that a deficiency in iodine leads to a less visible, yet more pervasive mental impairment that reduces intellectual performance in school and at work.[2]

Vitamin A deficiency

Vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of preventable blindness in children and it increases the risk of disease and death from severe infections. In pregnant women, vitamin A deficiency causes night blindness and may increase the risk of maternal mortality.[3]

Iron deficiency

Iron deficiency is the most common and widespread nutritional disorder in the world. Two billion people – over 30% of the world's population – are anaemic, many due to an iron deficiency, and in resource-poor areas this is frequently exacerbated by infectious diseases. Iron deficiency and anaemia reduce the work capacity of individuals and cumulatively, entire populations, bringing serious economic consequences and obstacles to national development.[4]

The issue of micronutrients

Micronutrient malnutrition (MNM) is a severe global health issue especially common in the developing world that can lead to increased mortality and morbidity. The Copenhagen Consensus 2008 Challenge Paper on ‘Malnutrition and Hunger’ estimated that maternal and child malnutrition is the underlying cause of 11% of total global DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years), and argued that combating MNM would be a crucial step towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals for primary education and child mortality.

The World Bank’s ‘Global Monitoring Report 2012: Food Prices, Nutrition, and the Millennium Development Goals’ stated that malnutrition – including MNM – could potentially impact all eight Millennium Development Goals.

It has also been suggested that micronutrient deficiencies can impact economic productivity, growth and development. For instance, researchers have claimed that iron deficiency causes China to lose 3.6% of Gross National Product through reduced productivity.[5]

Overall, the Copenhagen Consensus judged that combating malnutrition through micronutrient fortification was one of the highest-return investment opportunities in the world, with estimated cost- benefit ratios ranging from 7.8:1–39:1, depending on the micronutrients used.

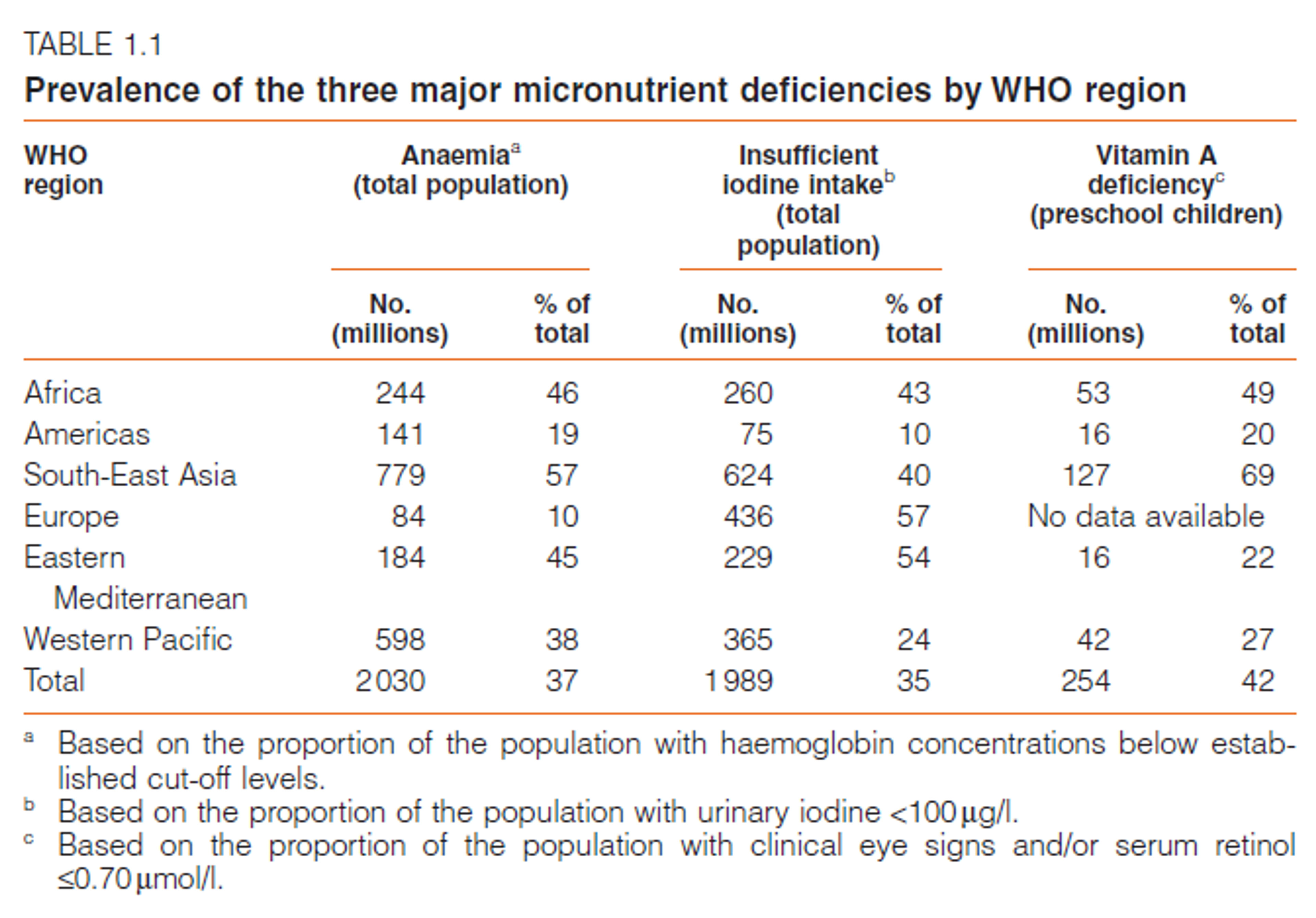

The three most important forms of MNM according to WHO’s ‘Role of Food Fortification’ report are iron, vitamin A and iodine deficiency. The WHO states that one in three of the world’s population suffer at least one of these deficiencies6, with the majority of individuals affected residing in the developing regions. Table 1.1 from this report shows the prevalence of these three deficiencies:

This report did not include data concerning the prevalence of other important deficiencies, such as zinc; it appears the public health implications of other deficiencies are less well understood.

The health impacts of micronutrient deficiency are estimated in WHO’s ‘Global Burden of Disease’ report: each year: iron-deficiency anaemia results in 25 million DALYs globally, vitamin A deficiency in 18 million DALYs and iodine deficiency in 2.5 million DALYs. These figures may underestimate the overall health impact of MNM, because DALY figures usually do not embody the smaller yet widespread health effects that can result from deficiencies, nor the effects these can have on cognitive abilities.

Apart from the ‘big 3’ deficiencies, many other micronutrient deficiencies appear to have severe health consequences. Diagram 1.2, constructed using information from the WHO report, gives a simplified overview of micronutrient deficiencies and their main health impacts.

Alleviating micronutrient malnutrition

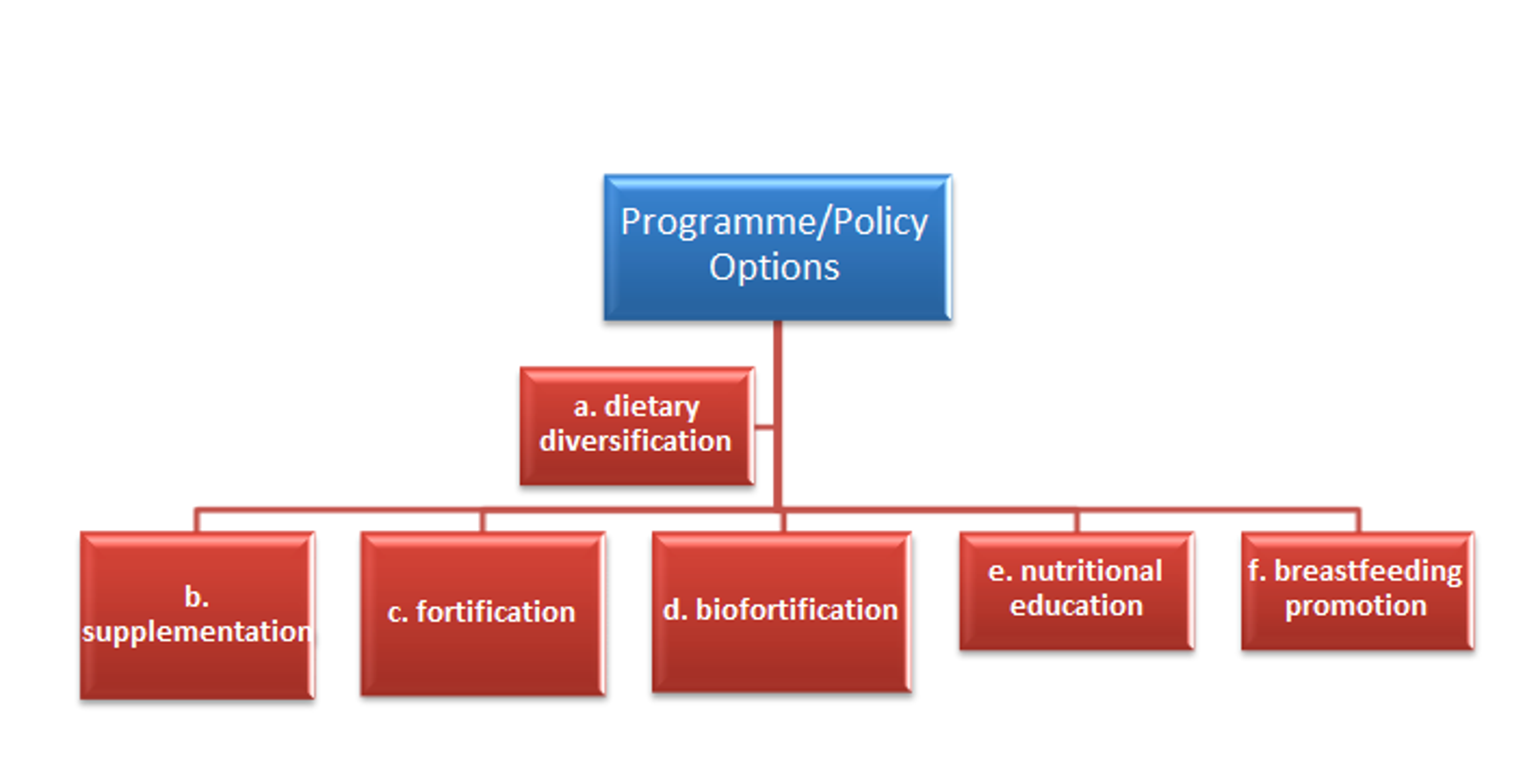

Diagram 1.2: Alleviating MNM

Dietary diversification might be the ‘ideal’ option for addressing MNM, which entails individuals receiving a varied and healthy diet. However, this approach would be very costly and take a long time to implement and reap the benefits.

Options b–d are approaches that are more likely to be effective, given scarce resources and time pressures. Other policy initiatives in developing countries include options e-f.[7]

What is fortification?

Fortification is the practice of deliberately increasing the proportion of micronutrients in food, to improve its nutritional quality and ultimately, to improve public health[1]

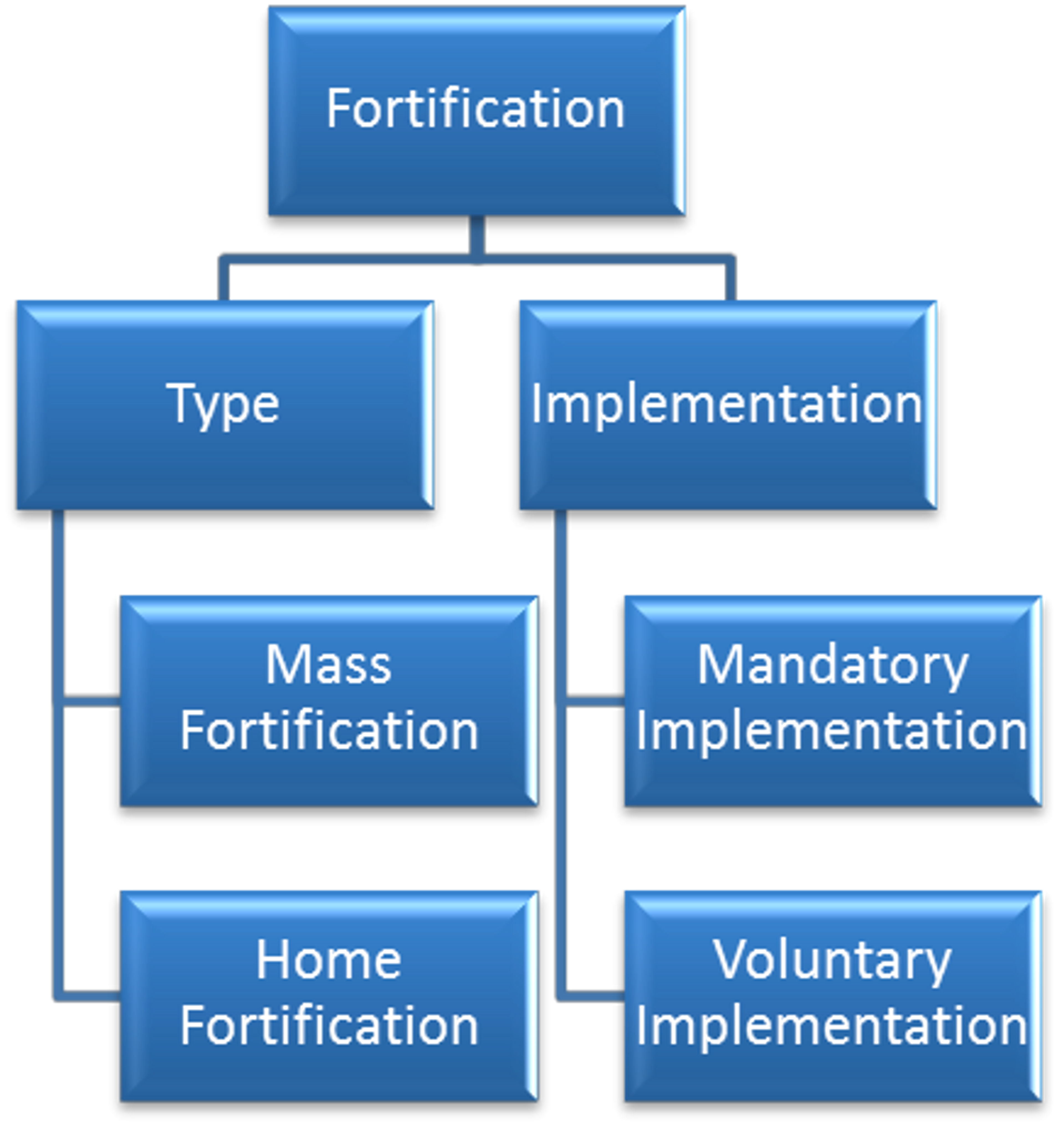

Referring to Diagram 1.3, fortification can be[2]

- Mass fortification: Micronutrients are added to foods at the time of processing, in factories or at local processing plants (e.g. mills).

- Home fortification: Micronutrients are added to foods at home before or after cooking (e.g. in the form of 'sprinkles').

- Mandatory: Fortification is required by law for minimally-processed staple foods. This is most cost-effective where a large proportion of the population is experiencing MNM. (It is important to note here, that even when fortification is mandatory, coverage will not necessarily be 100% of the target population due to reasons such as a weak legal infrastructure, which is the case for many developing countries.)

- Voluntary: It is up to the manufacturers whether to fortify their products. This is more common when MNM is less severe, and where the fortification of non-staple foods is considered.

Diagram 1.3: Types and Implementation of Fortification

The most common food fortification policy is that of salt iodisation7; the latest Global Unified Matrix database states that 55 out of 117 developing countries had legislation enacted for Universal Salt Iodisation by 2005 (and additional countries have enacted such legislation since then). Sugar is fortified with vitamin A in most of Central and South America, and it is estimated that around 95% of households are reached in El Salvador and Guatemala.[8]

How cost-effective is food fortification?

In principle, the main advantages of food fortification are as follows[9];

- Fortification of widely distributed and widely consumed foods has the potential to improve the nutritional status of a large proportion of the population, including rich and poor.

- Unlike dietary diversification, fortification requires no dietary changes, which are notoriously difficult to achieve.

- In most countries, the delivery systems for fortified foods are already in place.

- Several micronutrients can be added to foods simultaneously, without adding substantially to the cost.

- Most costs can be borne by private bodies (e.g. manufacturers).

Does it Work At All?

The Flour Fortification Initiative claims that seventy-five countries worldwide require fortification of one or more types of wheat flour. These include developed, transitional and developing countries.[10]

Empirical evidence from several studies suggests that fortification can be an effective means of reducing MNM. For example, we have found evidence that:

- Multi-micronutrient fortification led to increased school attendance and decreased morbidity from diarrhoea and respiratory diseases[11]

- Mandatory salt iodisation eradicated goiter in some countries[11]

- Fortification of salt with iron led to reduced anaemia among school children (dropping from 16.8% to 7.7% after a period of 10 months in the Indian state of Karnataka)[11]

- Following the distribution of free milk fortified with Vitamins A and D and iron, the prevalence of anaemia dropped from 62.3% to 26.4% in Sao Paulo[12]

- A single or multi-micronutrient fortification strategy in milk and cereals reduced the risk of anaemia by 50% in children aged six months to five years old, in a cross-country study[12]

However, some micronutrient fortification strategies have proved less effective. An example is the fortification of monosodium glutamate with Vitamin A in Indonesia, which was stopped due to political and technical issues (one of the technical issues was that, even though under laboratory testing the vitamin A remained white, once in the sun the product became discoloured which concerned producers and customers)[13]

Some potential disadvantages of fortification exist:

- Fortified foods may not be consumed by all members of the target population. Mass- manufactured fortified foods often do not reach the poorest rural members of the target population, for example, as these are more likely to produce their own food locally.

- There is insufficient evidence so far to rule out the concern that when several nutrients are added to food at once, biochemical reactions reduce their effectiveness. This concern has been raised by independent researchers14, as well as by the WHO[15]

- Manufacturer non-compliance with fortification regulation is a risk, especially in countries with weak legal infrastructure and/or high levels of corruption.

- Little comprehensive research has been done to estimate the overall health impact of mass fortification on a population. Most studies focus on small sample populations that consist of only infants, school children or breastfeeding mothers[16]

When it Works, Is it Cost-Effective?

Some evidence suggests fortification to be one of the most cost-effective strategies to deal with MNM. The Copenhagen 2008 ‘Malnutrition and Hunger Challenge’ Paper claims that zinc fortification costs only $12.20 per DALY averted, whilst zinc supplementation averts a DALY with each $63.

The Copenhagen Consensus 2008 states that iron fortification and salt iodisation are the second-most cost-effective strategies to cope with micronutrient deficiencies, with micronutrient supplements for children (vitamin A and zinc) coming first, and biofortification (breeding crops with enhanced nutritional benefits) coming third.

Cost per year of life gained

The WHO has a calculation they use to estimate the cost per year of life saved by Vitamin A fortification17. They take the current death rate for which vitamin A is responsible (deaths due to Vitamin A deficiency per 1,000 people), and assume fortification would bring this down to 0. They combine this with information about the cost per 1,000 people reached with fortification. Dividing years of lost life averted by cost, they produce an estimated cost per year of life saved of $18.60. This cost-effectiveness is extremely high.

Benefit:Cost Ratios

The WHO estimates a cost:benefit ratio for iodine fortification of 1:26.5, based on the assumption that iodine's unit cost is $0.10. However, they note that some experts put the unit cost as low as $0.01 in some areas of Sub-Saharan Africa (which would change the ratio to 1:265). The estimation assumes that iodine fortification will completely eradicate goitre in the treated area, which may be inaccurate. The costs of iodine deficiency in this model derive from productivity losses of 10% when pregnant mothers have goitre, so the calculations are also dependent on the country’s average wage.

The WHO estimates the economic returns for iron fortification (as a result of increased productivity) as $8 for every $1 spent (1:8 cost:benefit ratio), based on fortification costing $0.12 per person, reducing deficiency in 24% of the population, and economically benefiting each person helped by $4 of wages. However, the last figure ($4) is from a model of the Venezuelan economy - we should expect productivity gains to differ by country.

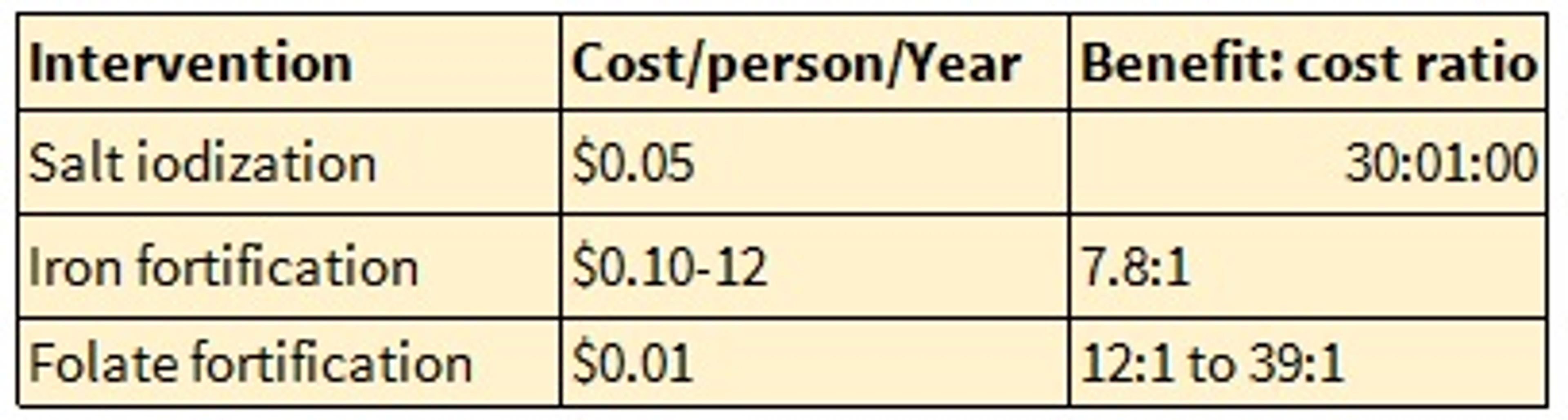

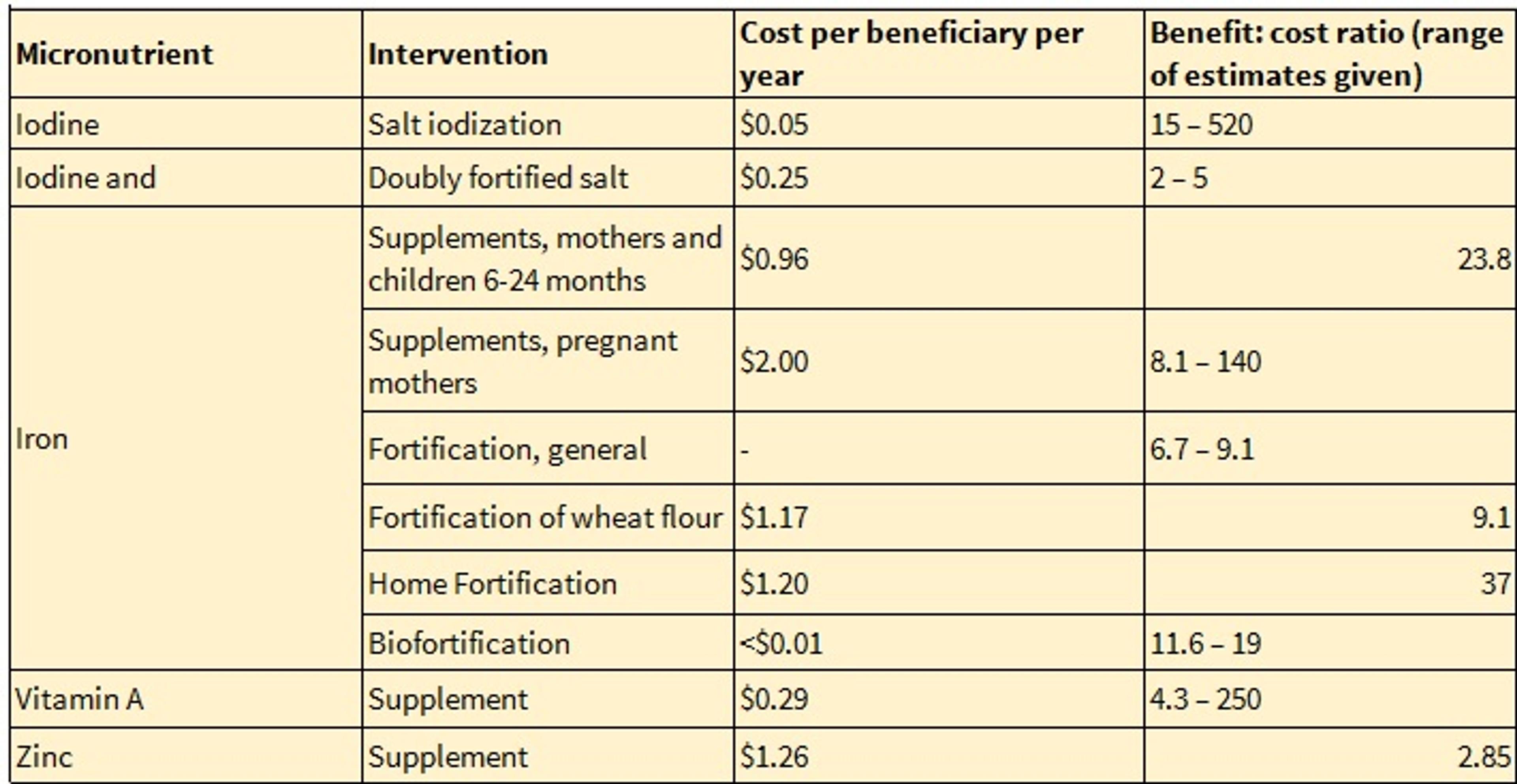

Table 1.4 summarizes the Copenhagen 2008 Malnutrition and Hunger Challenge Paper’s literature review of the cost-effectiveness of micronutrient fortification programmes. This paper uses benefit:cost ratios by converting DALYs averted into economic 'equivalents’[18]

Table 1.4: Summary of Micronutrient fortification benefit:cost ratios (CC 2008)

The more recent Copenhagen Consensus 2012 Challenge Paper on Hunger and Malnutrition published the following results (Table 1.5) from a further literature review on the benefit:cost ratios of micronutrient interventions.

Table 1.5: Summary of Micronutrient fortification benefit:cost ratios (CC2012)

CC12's estimate for the benefit:cost ratio of salt iodisation is promising, despite the very large range reported. This high benefit:cost ratio was derived from an average impact and cost across all individuals in the population, not just pregnant women or young children.

Cost:benefit ratios for iron fortification in general and of wheat flour in particular are lower than the proposed benefit:cost ratios of iron home fortification and iron biofortification (though the former may still be highly cost-effective).

DALYs/$1000

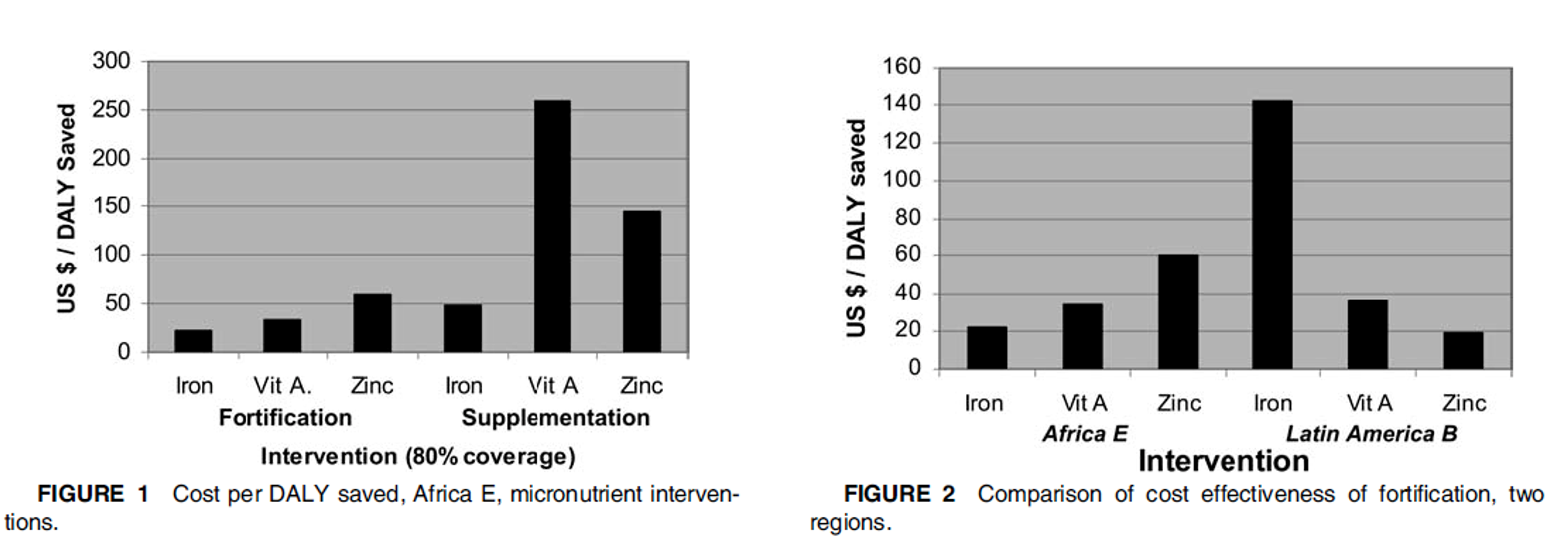

Sue Horton estimates the cost-effectiveness of mass fortification in terms of DALYs averted per $. Her results are depicted in Diagram 1.6[19]

Diagram 1.6. Horton’s Results: Cost-effectiveness of Fortification

Horton’s estimates compare the cost-effectiveness of iron, vitamin A, and zinc fortification and supplementation in the sample population, ‘Africa E’ (Fig. 1). She estimates that fortification is many times more cost-effective than supplementation. Each form of fortification averts a DALY for less than $60, suggesting high cost-effectiveness. Fig. 2 highlights her claim that the cost-effectiveness of fortification varies significantly by region.

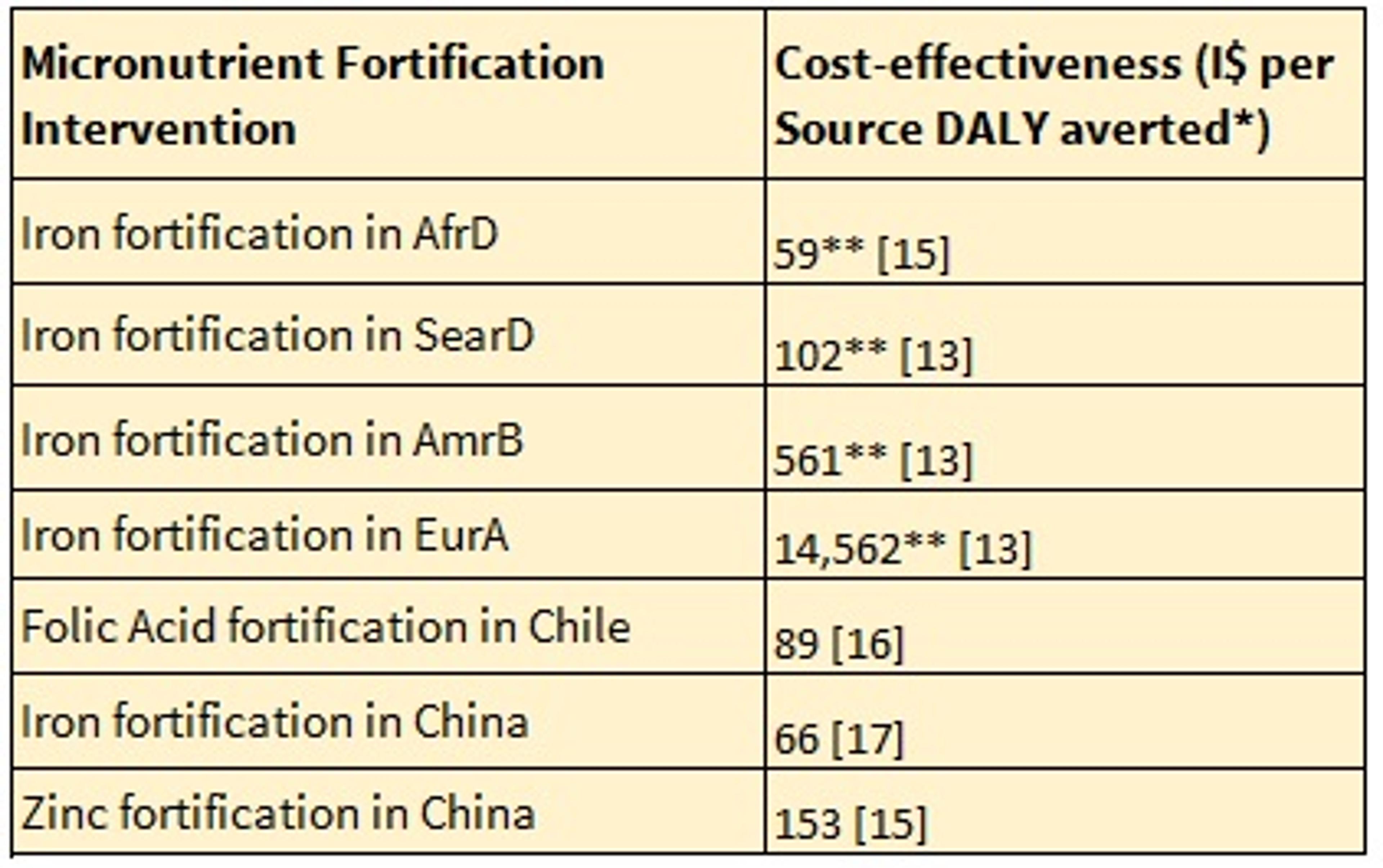

Table 1.7 summarises the cost-effectiveness (I$/DALY) estimates of several different approaches, detailed below.

Table 1.7. Summary of Literature: Cost-effectiveness of Fortification

*Costs are expressed in international dollars (I$), One I$ has the same purchasing power as one US$ has in the USA, costs in local currency units are converted to I$ by use of PPP. **Assuming 80% coverage. AfrD ,Africa subregion with high rates of adult and child mortality; AmrB, South American subregion with low adult and child mortality; EurA, European subregion with low adult and very low child mortality; SearD, Southeast Asian subregion with high rates of adult and child mortality.

The literature used to compile Table 1.7 makes the following claims about the cost-effectiveness of fortification compared to supplementation:

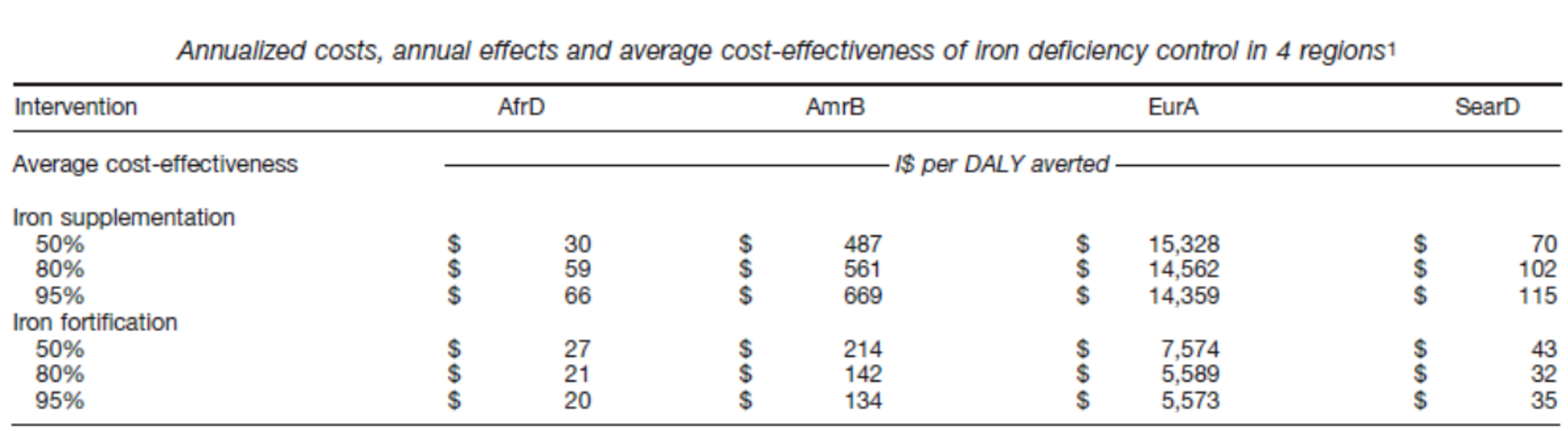

- Baltussen et al. (2004)20 estimate that iron fortification is more cost-effective than iron supplementation. See Table 1.8 for this study's estimates of the cost-effectiveness of iron fortification and supplementation at different levels of coverage.

- Ma et al. (2007)21 also estimate that iron fortification is more cost-effective than iron supplementation (I$179 per DALY averted) or dietary diversification (I$103 per DALY averted).

- Ma et al. (2007) estimate that zinc fortification is more cost-effective than supplementation (I$399), but less cost-effective than dietary diversification (I$103 per DALY saved).

Table 1.8: Cost-effectiveness of iron fortification and supplementation at 50% and 95% coverage rates:

Fortification has thus been found to be cost-effective at <$100 per="" daly="" averted="" in="" a="" variety="" of="" contexts.="" however,="" the="" cost-effectiveness="" differs="" several-fold="" by="" region="" and="" study,="" meaning="" that="" it="" remains="" challenging="" to="" confidently="" judge="" likely="" any="" particular="" future="" project.<="" p="">

Some concerns we have about relying on the existing literature are:

- Much of it is written by a small number of researchers.

- Some prominent researchers are also advocates for investment in this area, and may be inclined to overstate the effectiveness of fortification.

- It is hard to aggregate many small effects on health because each is individually hard to precisely measure; often these are not captured in DALY estimates (leading to underestimation of cost-effectiveness).

- The effectiveness of fortification varies significantly according to pre-treatment levels of deficiency, making it hard to generalise.

Sources:

- WHO summary of micronutrients

- WHO summary of iodine deficiency

- WHO summary of vitamin A deficiency

- WHO summary of iron deficiency

- Ma, G., Jin, Y., Li, Y., Zhai, F., Kok, F. J., Jacobsen, E., & Yang, X. (2008). Iron and zinc deficiencies in China: what is a feasible and cost-effective strategy?. Public health nutrition, 11(06), 632-638.

- Horton, S., Alderman, H., & Rivera, J. A. (2008). The challenge of hunger and malnutrition. Copenhagen Consensus.

- http://www.ffinetwork.org/.

- Darnton-Hill, I., & Nalubola, R. (2002). Fortification strategies to meet micronutrient needs: successes and failures. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 61(02), 231-241.

- Horton, S., Mannar, V., & Wesley, A. (2009). Food fortification with iron and iodine. Copenhagen Consensus Center Best Practice Paper. 2008.

- World Health Organization. (2006). Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Best, C., Neufingerl, N., Del Rosso, J. M., Transler, C., van den Briel, T., & Osendarp, S. (2011). Can multi-micronutrient food fortification improve the micronutrient status, growth, health, and cognition of schoolchildren? A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews, 69(4), 186-204.

- Eichler, K., Wieser, S., Rüthemann, I., & Brügger, U. (2012). Effects of micronutrient fortified milk and cereal food for infants and children: a systematic review. BMC public health, 12(1), 506.

- Berry, J., Mukherjee, P., & Shastry, G. K. (2012). Taken with a Grain of Salt? Micronutrient Fortification in South Asia. CESifo Economic Studies, 58(2), 422-44.

- Christian, P., & Tielsch, J. M. (2012). Evidence for multiple micronutrient effects based on randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses in developing countries. The Journal of Nutrition, 142(1), 173S-177S.

- World Health Organization. (2006). Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Bienz, D., Cori, H., & Hornig, D. (2003). Adequate dosing of micronutrients for different age groups in the life cycle. Food & Nutrition Bulletin, 24(Supplement 1), 7S-15S.

- Allen, Benoist, Dary and Hurrell (2006). Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva: World Health Organization & Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- “Note that the values assigned in the Copenhagen Consensus project areas follows: with a life expectancy of 60 years, a 3% discount rate, and a DALY value of $1000, a life saved (in infancy) is worth around $28,505; the same life saved is worth just $17,131 with a 6% discount rate. The same calculation at a DALY value of $5000 implicitly values a human life saved at birth at $142,525 with a 3% discount rate, and $85, 665 at a 6% discount rate” [Horton, Alderman & Rivera (2008) The challenge of hunger and malnutrition. Copenhagen Consensus.]

- Horton, S. (2006). The economics of food fortification. The Journal of nutrition, 136(4), 1068-107.

- Baltussen, R., Knai, C., & Sharan, M. (2004). Iron fortification and iron supplementation are cost- effective interventions to reduce iron deficiency in four subregions of the world. The Journal of nutrition, 134(10), 2678-2684.

- Ma, G., Jin, Y., Li, Y., Zhai, F., Kok, F. J., Jacobsen, E., & Yang, X. (2008). Iron and zinc deficiencies in China: what is a feasible and cost-effective strategy?. Public health nutrition, 11(06), 632-638.

Last updated: 2013