Blindness

Giving What We Can no longer conducts our own research into charities and cause areas. Instead, we’re relying on the work of organisations including J-PAL, GiveWell, and the Open Philanthropy Project, which are in a better position to provide more comprehensive research coverage.

These research reports represent our thinking as of late 2016, and much of the information will be relevant for making decisions about how to donate as effectively as possible. However we are not updating them and the information may therefore be out of date.

Read our most recent report here

The two main causes of blindness, cataracts and trachoma, are both curable with reasonably cheap surgery. Several charities provide this at moderately cost-effective rates, but none are as cost-effective as drug-based treatments for other diseases.

Cataracts

A cataract is clouding of the lens of the eye, which impedes the passage of light. Most cataracts are related to ageing, although occasionally children may be born with the condition, or cataracts may develop after injury, inflammation or disease. Vision can be restored by surgically removing the affected lens and replacing it with an artificial one.[1]

Trachoma

Trachoma is a contagious bacterial infection that is frequently passed from child to child and from child to mother, especially where there are water shortages, numerous flies, and crowded living conditions.

Infection often begins during infancy or childhood and can become chronic. If left untreated, the infection eventually causes the eyelid to turn inwards. This causes the eyelashes to rub on the eyeball, resulting in intense pain and scarring of the front of the eye. This ultimately leads to irreversible blindness, typically between 30 and 40 years of age.[2]

Cost-effectiveness

For each of these conditions, there is a fairly simple surgical operation.

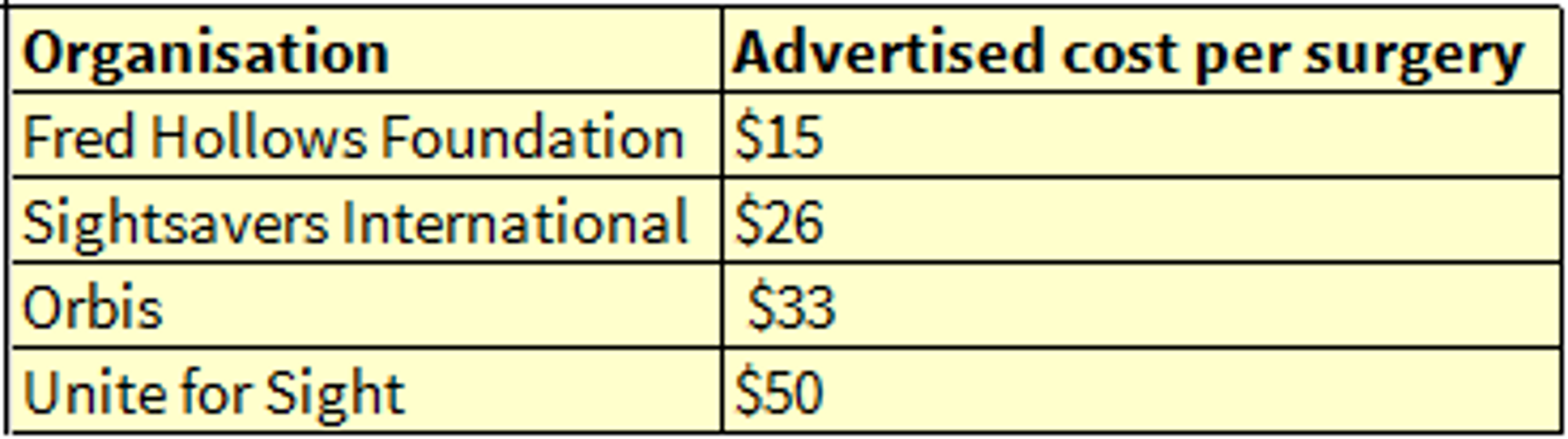

Charities that focus on blindness often advertise their cost-effectiveness in terms of the amount of money one sight-saving surgery costs (note that one surgery is carried out per eye, so someone who is blind in both eyes will require two surgeries):

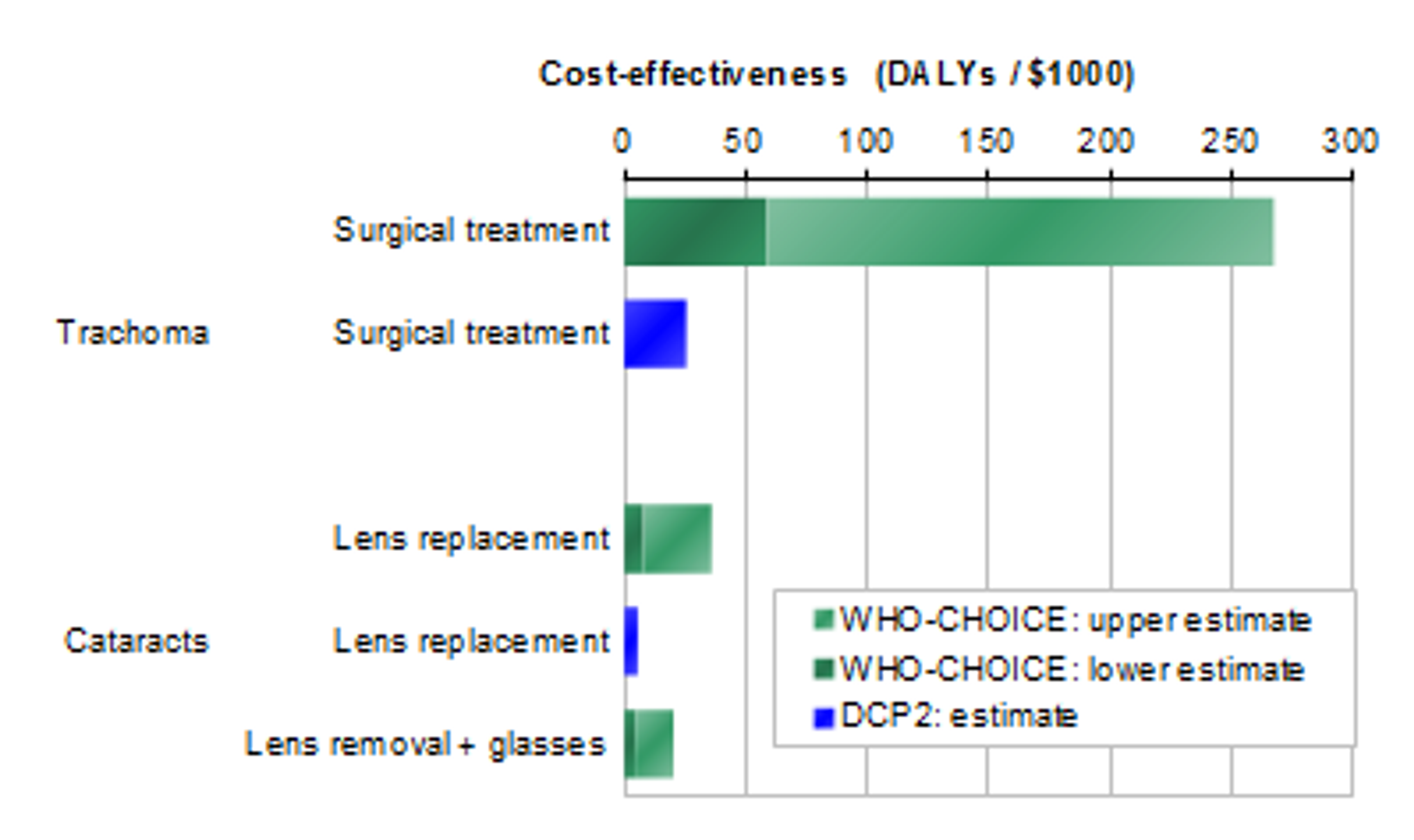

In other words, according to the WHO-CHOICE report, it would cost $10 to completely restore, by targeted trachoma surgery, the sight for ten years of a person in a developing country who is completely blind.3 According to the DCP2 report, it would cost $1,098 to completely restore, by extracapsular extraction, the sight for ten years of a person in a developing country who is completely blind.

The difference between the DCP2 and the WHO-CHOICE estimates for trachoma surgery is notable. This might be explained by the fact that trachoma surgeries require many goods to be bought at international, rather than local prices; whereas the WHO assumes that all goods are bought at local prices.

The reasons for the difference between the cost-effectiveness estimates from WHO-CHOICE and DCP2 and estimates from charities shown in the table above are as follows. First, it is possible that the charities are not quoting the ‘all things considered’ cost of a surgery (that is, including transport, administration costs, etc.). Secondly, many people undergoing eye surgery are partially sighted and not completely blind; and thirdly, the majority of these patients are very elderly and thus do not gain as many years of sight as one might expect.

For these reasons, we believe the charities' estimates are compatible with the DCP2 and WHO-CHOICE estimates.

Other information

All health interventions have side effects, both good and bad.

Some of the possible side benefits of eye surgeries include:

- Economic benefits: the patient no longer needs care and can become independent and economically productive again.

- Little effect is observed on the country’s population size.

One possible side cost is:

- Doing these surgeries may reduce the number of surgeons working in other areas, changing who gets treated for what, but not changing how many people get treated in total.[4]

Conclusion

Charities that focus on eye surgery certainly do a lot of good for many people, with little risk of side effects. However, based on the evidence currently available, eye surgery charities appear to be less cost-effective than gold-standard interventions such as bed nets for the prevention of malaria or drugs for the treatment of neglected tropical diseases. As such, eye-surgery charities are not cost-effective enough for us to give them our highest recommendation; we therefore suggest that donors consider other intervention types.

Sources

- WHO summary of cataracts

- WHO summary of trachoma

- Curing someone completely of blindness for 10 years is equivalent to averting 6 DALYs, because blindness has a disability weighting of 0.6.

- See for example, the GiveWell article 'Developing World Corrective Surgery'.

Last updated: in or before 2012