The literature on economic development has begun to study the potential for mass media in development (Roy, 2014). Information can support citizens to make more informed decisions in many areas of their lives, including health and politics. However, research shows that changing attitudes and knowledge does not necessarily translate into the desired behaviour changes (Nag, 2011). Any successful development media campaign will need to overcome barriers to impact, such as a failure to understand the underlying reasons for existing practices.

A new project launched by Development Media International (DMI) is attempting to realise the potential of mass media to change behaviour in useful ways in the developing world. DMI is a UK-based NGO that delivers radio and TV campaigns in the developing world (see more here, with plans to reach 10 African countries. DMI’s current focus is reducing child mortality and morbidity in children under five. The reason for this focus is that the majority of child deaths in this age bracket are the result of a lack of basic practices such as early breastfeeding or diarrhoeal treatment.

In conjunction with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), DMI is the first organisation to combine mass media campaigns with scientific modelling to predict health outcomes. Initial estimates from such modelling predict a potential 10-16% reduction in child mortality, at an estimated cost of $60-$300 per life saved, potentially making this the most effective lifesaving intervention available. According to the Lancet Child Survival Series, 6.9 million children under 5 perish each year as a result of the issues DMI is addressing. Assuming a high coverage rate, and given the estimated cost-effectiveness of this project, DMI’s potential annual impact on child mortality is striking. Of course we should be cautious about such estimates, but they do justify further investigation.

DMI has designed its campaigns to address 3 key main aims concerned with:

- Behaviour change to save the most lives in a given country and context;

- Tackling key barriers such as cultural norms and religious beliefs that commonly impede behavioural change;

- Reaching the largest number of people in the most effective way based on carefully selected media partnerships, demographic profiles, geographical locations and language preferences of their target audience at the most effective times of day over a sustained period.

Whilst child survival remains the main focus of DMI, DMI is also targeting a range of other related healthcare issues issues such as sexual and reproductive health, nutrition, hygiene, environmental health and both communicable and non-communicable diseases. This puts them in a good position to make an impact on four of the eight Millennium Development Goals, improving gender equality, child survival, maternal health, and HIV/Aids and malaria.

DMI is avoiding the common selection bias frequently attributed to existing studies in development media by conducting a randomised controlled trial of one of their radio health projects in Burkina Faso to evidence their impact. They have attracted the attention of GiveWell, who have described the preliminary results from their trial here. Although preliminary midline results from a randomized controlled trial appear promising, GiveWell expects to conduct a more thorough evaluation of DMI this year, and will withhold judgement until this is complete.

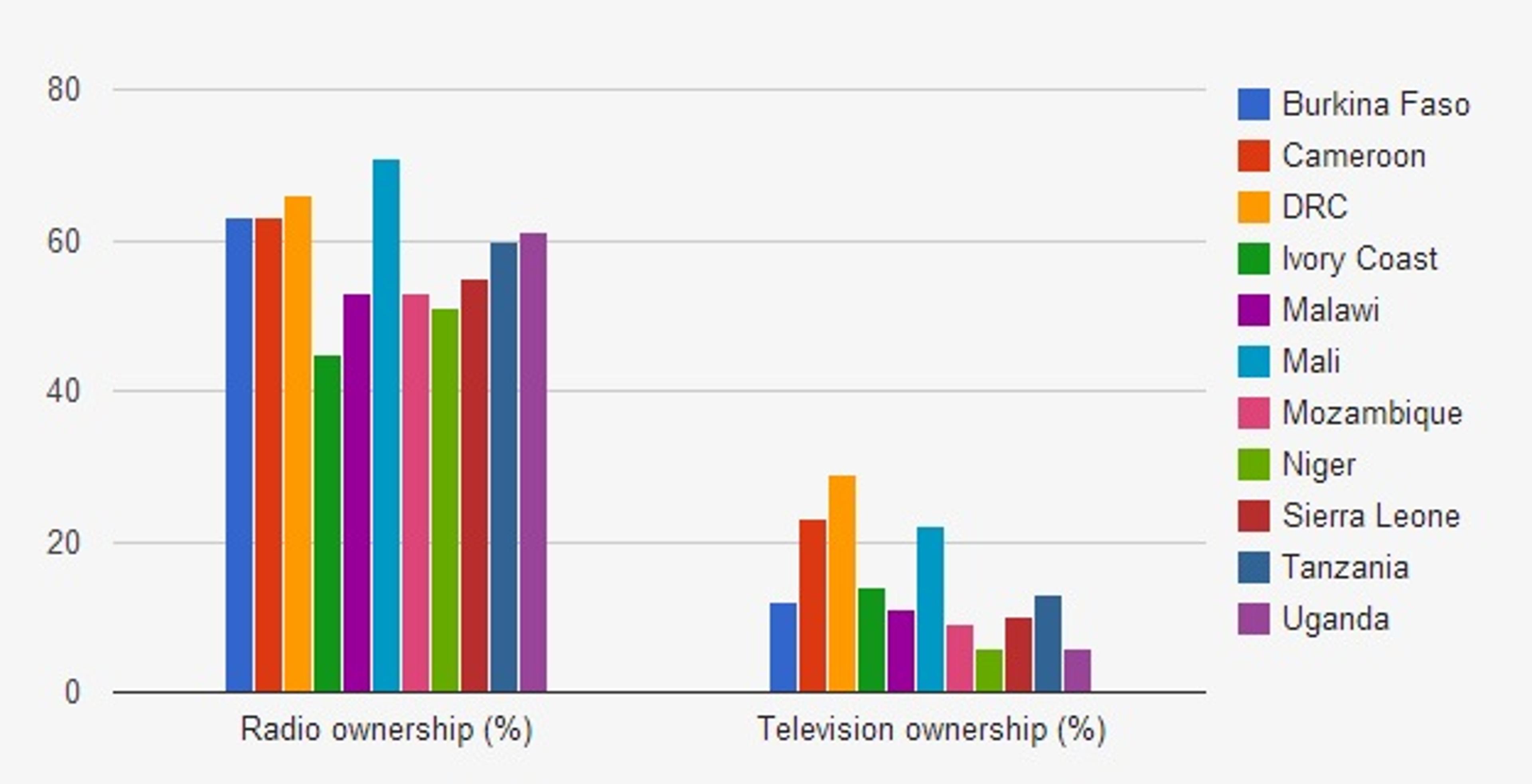

Using research gathered, DMI have found that their target audiences are most likely to have access to and actively listen to the radio as opposed to the television. In Uganda, as many as 74% of the population listen to the radio at least weekly, compared with only 11% watching television in the same period. Audiences are most receptive to emotionally evocative stories rooted in everyday life delivered in a narrative form. Using a 3-part dramatic structure delivered in the local language, DMI uses the power and perseveration of emotional responses on memory to enact behaviour change in its audience. This 3-part structure lends itself to the intentions of behaviour change, as the dramatic character is forced to overcome an obstacle through behaviour change before he/she can achieve resolution.

The countries chosen for DMI’s current campaigns have been designed to achieve maximum efficacy, by combining those countries with high maternal and child mortality rates that also stand to benefit most from mass media intervention due to average to high media penetration. Behavioural change is implemented “at three levels: in households, in the wider community, and in people’s use of health facilities and services”.

The versatility of DMI’s story development enables multiple interconnected health issues to be addressed, leading to improved health outcomes not necessarily restricted to any one domain. For example, campaigns centred around child health can also serve to reduce neonatal mortality, maternal health, hygiene and nutrition via the promotion of health facilities to give birth or monitor pregnancy. Rather than diluting the focus of a given intervention, evidence suggests that there is only a small reduction of impact on each issue, and because adding another issue to an existing campaign only fractionally increases the cost, the cost-effectiveness is much greater.

In conclusion, a preliminary examination of DMI shows promising results in the development and delivery of mass media public health interventions towards reducing child mortality, morbidity and maternal health via an extremely cost effective medium. It remains to be seen whether the initial results of DMI’s study are statistically significant at closer examination, as the self-reported nature of the initial assessment has raised social desirability bias concern. Development Media International aims to address these concerns in their later endline study results, which will specifically measure child mortality statistics as opposed to subjective self reports. You can expect a later blog post from us reporting on these findings, but so far we are excited by the efforts of DMI in targeting hard-to-reach audiences in a cost-effective way, as well as their unique potential to effect behaviour change on a population level.

A closing thought...

If mass media interventions prove socially desirable merit goods in the development process, then a strong case should be made for their wide diffusion among the populace in order to reach the most technologically alienated audiences (Nag, 2011). If they are to act as tools of social inclusion, economic opportunity and empowerment, targeted efforts need to be made to provide access to content, opportunities and tools geared towards the priority needs of a given community. On a broader level, both governmental and non governmental organisations should form a collaborative effort towards the provision of technology to safeguard against the marginalisation of traditionally excluded and disadvantaged groups from effective public health campaigns, such as those employed by DMI (Nag, 2011).

References:

Nag, B. (2011). Mass Media and ICT in Development Communication: Comparison & Convergence. Global Media Journal: Indian Edition, 2(2), 1-29.

Roy, S. (2011). Media Development and Political Stability: An Analysis of Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, Internews.[Online] www. MediaMapResource. org (Accessed May 25, 2014).

Image source: DMI website